I moved to Darwin in 1980 and worked for the Public Service Credit Union and then the Territory Building Society until the mid 80s when I saw an opportunity to go over to the dark side and I got a job with the financial management subsidiary of one of the big four banks. The industry was very much based upon the culture of the huge [and very successful] insurance mutuals; salary was a base retainer but to make a living wage one had to generate commission on sales and a FuM [funds under management] fee. New employees were sent to Melbourne to obtain a license to give advice, but it was all a bit of a sham really – nobody failed, much like the RTOs of today. All of the training we received was how to maximise sales – very little, if any information about acting in the customers best interest, was given.

I didn’t make a lot of money because usually customers just wanted guidance, they weren’t ready to invest in the securities market [shares], superannuation was still primarily the province of public servants and it was sales of managed funds, primarily bank owned funds, that generated commission, not advice. The licencee absolutely forbid fee for service – i.e. charging the customer a fee for giving advice, especially if that advice was ‘do nothing’. Most people got their advice from the footy club or the pub. The only referrals from the bank managers [supposedly the major source of business] were for ‘minimising tax’. The biggest Darwin investors put all their money in real estate – the concept of asset diversification for the majority meant having a property in different suburbs. By the mid 90s it was becoming apparent that superannuation was to be the big earner, that ‘set and forget’ plans generating continuing fees were the most remunerative and little attention was paid to asset diversification, risk management, estate planning etc. all the things that a responsible financial planner was supposed do. A family tragedy gave me the opportunity to exit the industry before it became really bad and left me with a much better idea of what went on in the board rooms. I couldn’t forsee the depths to which the whole industry would sink in pursuit of dishonesty and greed.

[Much of the following has been copied from the Royal Commission interim report.]

The traditional business of banking comprised lending, deposit-taking and the provision of transaction services. Through the first half of the 20th century, banking was a highly regulated, local, low risk business based on a customer’s credit worthiness and yielded returns based on [often quite low rates of] interest. During the 1950s, banking had little to do with funds management, run largely by superannuation and life insurance mutuals where they pooled and invested money on behalf of policy holders and the profits retained within the organisation for the benefit of members. The reach of this sector was limited until regulatory and financial conditions changed in the 1970. Restrictions on bank interest rates and liability structures were removed; foreign banking was made easier to access; the Australian dollar was floated. The financial sector expanded. At the same time, growth in the size and liquidity of securities markets allowed more diverse financial products to develop.

The next critical steps were the expansion of superannuation, which shifted the responsibility for, and control of, provision for retirement from employers to individuals. Before the early 1980s, Australians who required financial advice often went to their bankers, accountants and insurance advisers. From 1983, successive changes to the tax treatment of superannuation established it as a vehicle for compulsory saving and increased its complexity. These developments included the incorporation of superannuation into employment awards and legislation imposing tax penalties where employer contributions were not made. With greater amounts of savings invested in super funds, Australians now have a far higher exposure to capital markets and since the 1980s Australians have been subject to heavy advertising establishing a need for financial advice.

As the market for superannuation and investment products grew, the life insurance and other financial institutions that manufactured financial products looked to financial advisers to sell them. At that time most financial advisers came from a background of life insurance, in which a sales-driven, commission-based culture prevailed and comprehensive advice was not usually sought or given. These being the roots of the financial planning industry, the culture, with all it’s faults and inadequacies, endured. The 1990s brought even more of the Australian public into the market for financial products and services, and therefore advice. A series of privatisations [such as CBA, Telstra and Qantas] and demutualisations [such as AMP and NRMA Insurance] increased middle class share ownership. When AMP demutualised in 1998 it did so with an excess of capital. It went on a spending spree, buying UK funds manager Henderson, National Provident and then GIO, a $3-billion investment that lost $1 billion. By 2003 its share price had hit a record low $2.72, having lost shareholders 73 per cent in value since listing.

Many participants in demutualisations and privatisations were first-time shareholders leading to one of the highest rates of share ownership in the world, with 36 per cent of Australians holding shares directly or indirectly through their super funds. The CBA is a good example with more than 800,000 Australian households owning what has become the biggest bank in Australia. CBA listed through the offer of 30 per cent of its shares to the public at $5.40 a share. The offer raised $1.3 billion and the closing price on CBA’s first day of trade was $6.46. A $2,160 investment in CBA during its initial public offering – 400 shares at the minimum subscription – is now worth $131,371 for those who reinvested their dividends. In 25 years as a listed company, CBA delivered a total shareholder return of 9,500 per cent, a seriously profitable company.

Further deregulation of the financial sector contributed to a surge in credit provision and the design of new and more complex financial products. These developments in combination with the prevailing low interest rates raised household indebtedness and increased the value of market-linked financial assets households held. At this time, banks were beginning their expansion into wealth management resulting in Treasury releasing its Corporate Law Economic Reform Program Paper No. 6 [CLERP 6]. Although extensive amendments have been made to the legislation passed to implement CLERP 6, a number of its underlying principles have endured.

One of those principles was to fold sales and advice relating to insurance and superannuation into the regulation of securities. That regulatory framework was premised on independent intermediation and the use of mandatory disclosure as a means of investor protection. It did not take into account that insurance and superannuation decisions were usually made with consumption [a payment in case of injury; an income stream at retirement], rather than investment, in mind, or that those products were usually sold by sales agents and not independent brokers like those who traded in securities. Finally, CLERP 6 established that household access to wholesale markets and complex products would not be restricted. Rather, it relied on mandatory pre-disclosure as the means to inform consumers about risks on the basis that consumers would then make informed and rational choices about the best investment strategies for them. That meant leveraged and complex investments could be marketed and sold in the retail market.

From the time of the Wallis Inquiry, banks’ accumulation of wealth management businesses accelerated when each of the major banks acquired or merged with a fund manager. The vertical integration of product manufacture with product sale and financial advice is a ‘one stop shop’ vision in which retail customers’ investment needs can be provided alongside traditional banking facilities such as loan and deposit services. Vertical integration has seen the acquisition by entities of all of the steps in supply of financial products, starting with designing and creating the product, providing asset management services and investment platforms, and distribution to customers by way of financial advice or sales. Vertical integration promises the virtue of efficiency, which, in a competitive market, should then passed on to consumers in the form of lower costs and greater access to financial advice. Customers would also enjoy the simplicity of dealing with just one institution. But the internal efficiency of the ‘one stop shop’ does not necessarily produce efficiency in outcomes for customers. The one-stop shop has an incentive to promote the owner’s products above others, even where they may not be ideal for the consumer.

From the deposit taking institutions perspective, vertical integration always promised the benefit of cross-selling new financial products to existing and new customers. In 2000, CBA acquired Colonial Mutual Life Assurance Ltd, which conducted life and other insurance business, and a funds management business. In 2000, NAB acquired the financial services businesses of Lend Lease, including MLC Holdings Ltd. In 2002, ANZ entered joint venture arrangements with ING Group in respect of wealth management and life insurance businesses in Australia and New Zealand, and later acquired the full business. Westpac took a different path and founded Magnitude Group. In 2008, as part of its merger with St George Bank, Westpac acquired St George’s financial advice business, which included employed advisers as well as Securitor Financial Group Ltd. In 2002, Westpac acquired all of BT Financial Group’s asset accumulation businesses. By contrast with the banks, AMP’s structures remained substantially unchanged. AMP has a network of about 2,800 financial planners. About 90% of those are self-employed and act as authorised representatives of one of the various AMP advice licensees which are subsidiaries of AMP.

By the time of the Murray Inquiry, the ‘one stop shop’ model was well established in the market. The report observed that the high concentration and steadily increasing vertical integration in some sectors had the potential to limit the benefits of competition. While the report did not express a view as to the merits of vertical integration, the Murray Inquiry recommended ways in which to make ownership and alignment more transparent. It did, however, note that the Global Financial Crisis had exposed ‘significant numbers of Australian consumers holding financial products that did not suit their needs and circumstances’ and that there were ‘significant problems relating to shortcomings in disclosure and financial advice’.

By the time of the Murray Inquiry, the ‘one stop shop’ model was well established in the market. The report observed that the high concentration and steadily increasing vertical integration in some sectors had the potential to limit the benefits of competition. While the report did not express a view as to the merits of vertical integration, the Murray Inquiry recommended ways in which to make ownership and alignment more transparent. It did, however, note that the Global Financial Crisis had exposed ‘significant numbers of Australian consumers holding financial products that did not suit their needs and circumstances’ and that there were ‘significant problems relating to shortcomings in disclosure and financial advice’.

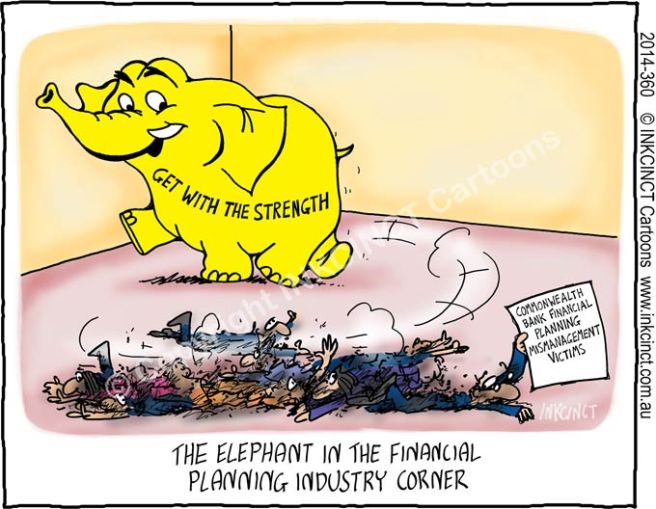

Shortly before the second half of 2008, Storm Financial was a profitable company with $77 million in annual revenue and $120 million in consolidated gross assets. Initially conducting its business in north Queensland by 2008, Storm Financial had offices in a number of States and had over 100 employees conducting business throughout most of Queensland and in many other parts of Australia, attracting thousands of new customers. The business model of Storm Financial was to provide advice in standard or template form, with minimal tailoring to the investor. Almost 90% of Storm’s clients were encouraged to take out loans against the equity in their own homes, and use the funds from these loans to invest in the share market via index funds and to negatively gear residential properties. In early 2009, many clients of Storm Financial were in negative equity positions, sustaining significant capital losses. This resulted in many investors losing their investment, their homes and their life savings and still having significant debts outstanding. Most of the loans made were recourse loans which permit the lender to fully recoup their losses by choosing to seize other assets, or pursue legal action to seek financial damages. Recourse loans mean that the lender is fully covered, even after the asset is seized and sold, any remaining debt is still owed by the borrower.

ASIC estimated the total loss suffered by all investors who borrowed from various banks to invest through Storm to be approximately $832 million. Way after the horse had bolted, ASIC commenced an investigation into Storm Financial and it was placed into voluntary administration and a liquidator appointed. ASIC commenced legal proceedings in relation to the scandal including alleging that the directors had breached their fiduciary duties and that advisors had provided inappropriate advice. In March 2018, the Federal Court imposed a penalty of $70,000 [from a maximum penalty of $200,000] on each of the directors of Storm Financial and ordered that each be disqualified from managing corporations for seven years. ASIC also entered into;

• a settlement agreement with CBA to make available up to $136 million as compensation to CBA customers who had borrowed from the bank to invest through Storm Financial.

• a class action brought against Macquarie Bank in respect of Storm Financial regarding the fairness of settlement arrangements. The Full Federal Court held that the distribution of the settlement sum was not fair and reasonable to all group members and a revised settlement arrangement was arrived at whereby Macquarie Bank agreed to pay $82.5 million by way of compensation and costs.

•a settlement agreement with the Bank of Queensland to pay approximately $17 million as compensation for losses suffered on investments made through Storm Financial.

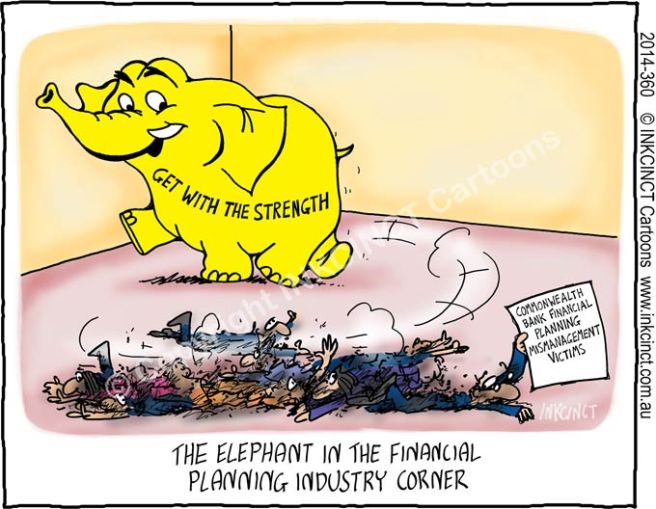

Rhetoric of the kind that ‘a small number of individuals in our advice business made the decision not to follow policy, and inappropriately charged fees to customers where no service was provided’ is common. And responses to revelations of wrongdoings are generally accompanied by apologies and undertakings to take steps to restore public trust. For example, following the CFPL scandal, Ian Narev, then CEO of CBA, noted that CBA ‘must now focus on restoring trust with all our financial planning customers and the community generally.’ Similar commitments were made after the Comminsure scandal in early 2016 and again in 2017 in relation to the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre (AUSTRAC) investigation into money laundering through CBA ATMs. That generally similar conduct occurred in all of the major entities suggests that the conduct cannot be explained as ‘a few bad apples’. That characterisation serves to contain allegations of misconduct and distance the entity from responsibility. It ignores the root causes of conduct, which often lie with the systems, processes and culture cultivated by an entity. It does not contribute to rebuilding public trust in the financial advice industry.

And the CBA refuses to clean up it’s act, witness a report by SMH reporters Chris Vedelago & Cameron Houston on 11 May 2018.

A Commonwealth Bank loans officer who perpetrated a $3.5 million fraud on the bank …… was never reported to police, allowing him to continue working in the financial services sector. Former Melbourne-based mobile lender George Vrettakos told the bank that others were implicated in his behaviour but the bank appears to have never followed up the information he provided. “I’m not gonna sit there and cop it because, yes, I did wrong, but I wasn’t the only one. I was taught how to do it,” Mr Vrettakos said during a recorded interview with the bank’s group security department obtained by The Age. “If we want to talk seriously, there is a hundred witnesses for stuff that was being done”. The bank did not report the scam to police or regulators. Mr Vrettakos was instead sacked and offered a confidential settlement deal that required him to pay back up to $2 million of the stolen funds. “George, as you are aware our profession is founded on very high standards of personal integrity and conduct which requires absolute honesty,” the CBA’s regional general manager wrote in Mr Vrettakos’ termination letter.

“The bank considers your actions to be a serious breach of the bank’s lending policies and statement of professional practice … You should comply with the law in all your activities.”

In an attempt to cover up a similar situation, NAB said that to provide details of misconduct that had occurred over the preceding five years it would have to look at, among other things, the Annual Compliance Statements it had made under the Code of Banking Practice [which recorded 1,914 breaches of the Code in the last five full financial years], 300 events reported as significant breaches to ASIC or APRA occurring during that period, 370 Financial Ombudsman determinations, 375 determinations by the Credit and Investments Ombudsman, 246 significant litigation matters and five different databases recording customer complaints. Taken together, the course of events and the explanations proffered can lead only to the conclusion that neither CBA nor NAB could readily identify how, or to what extent, the entity as a whole was failing to comply with the law. And if that is right, neither the senior management nor the board of the entity could be given any single coherent picture of the nature or extent of failures of compliance; they could be given only a disjointed series of bits of information framed by reference to particular events. Information presented in that way points too easily towards explaining what has happened as ‘a small number of people choosing to behave unethically’ or as the product of ‘people, policies and processes that existed with a pocket of poor culture in that area at that time’.

Two themes recurred: dishonesty and greed.

Charging for doing what you do not do is dishonest.

Giving advice that does not serve the client’s interests but profits the adviser is equally dishonest.

No matter whether the motive is called ‘greed’, ‘avarice’ or ‘pursuit of profit’, the conduct ignores basic standards of honesty.

Its prevalence and persistence require consideration of the issues of culture, regulation and structure.

In their submissions to the Royal Commission, financial services entities acknowledged conduct that amounted to misconduct or conduct falling below community standards and expectations in connection with the provision of financial advice. The following is a summary of the conduct acknowledged by the entities in relation to fees for no service, inappropriate advice and improper conduct by advisers.

CBA identified instances in the period from July 2007 to June 2015 where clients of CFPL, BW Financial Advice and Count Financial were charged ongoing fees for financial advice where no such services were provided. CBA acknowledged that as at 31 December 2017, approximately $118.5 million in refunds has been offered or paid to customers affected by this conduct. Again, very soon before the Commission was to begin taking evidence on these matters, on 9 April 2018, CFPL and BW Financial Advice entered into an enforceable undertaking with ASIC in relation to a failure to provide, annual reviews to approximately 31,500 ‘Ongoing Service’ customers.

CBA acknowledged that in the period since 2013:

• It had made 20 breach notifications to ASIC in relation to actual or likely breaches of the Corporations Act by an adviser licensed by CFPL, Financial Wisdom or Count Financial.

• It had made a further five breach notifications in relation to advisers identified through file reviews applied to the financial services licences held by CFPL and Financial Wisdom.

• It had made notifications in respect of a further 20 advisers in relation to serious compliance concerns.

• It had made good governance notifications in respect of a further 13 advisers, which largely related to signature irregularities in documents on client files.

• Fifteen former CBA employees or representatives have been the subject of ASIC banning orders or enforceable undertakings.

In its third submission to the Commission, CBA acknowledged 76 specific events of misconduct over the last five years that related to financial advice. These included instances of problems with customer documentation and signatures, failure to comply with disclosure requirements, and asset allocations that failed to align with customer risk profiles.

Clients seldom complained about being charged for nothing. They did not complain because the fees they paid were charged invisibly.

• Whether the conduct is said to have been moved by ‘greed’, ‘avarice’, or ‘the pursuit of profit’, it is conduct that ignored the most basic standards of honesty.

• The licensees did nothing to stop it and they took the proceeds.

• The conduct of licensees and advisers was inexcusable and no-one has since tried to excuse it.

• No-one has been subjected to any formal public process of investigation, finding and punishment for this conduct. Only at the last minute before the hearings began, did enforceable undertakings yield public (and then very limited) formal acknowledgment from entities that ASIC had ‘concerns’ about their conduct and that those concerns were ‘reasonably held’.

• Even when the Commission was taking evidence about the issue, the licensees had not made good their defaults by compensating all their affected clients.

The nature and extent of the ‘fees for no service’ issue was described in the evidence of Mr Kell, Deputy Chair of ASIC. As at 2018, AMP, ANZ, CBA, NAB and Westpac had paid, or agreed to pay, to almost 306,000 customers, combined compensation of more than $216 million. Three of those entities, ANZ, CBA and NAB, had reported to ASIC that they estimated that further compensation of at least $2.5 million would be paid.

The nature and extent of the ‘fees for no service’ issue was described in the evidence of Mr Kell, Deputy Chair of ASIC. As at 2018, AMP, ANZ, CBA, NAB and Westpac had paid, or agreed to pay, to almost 306,000 customers, combined compensation of more than $216 million. Three of those entities, ANZ, CBA and NAB, had reported to ASIC that they estimated that further compensation of at least $2.5 million would be paid.

Part of the problem can be squarely laid at the feet of the regulator. In 2014, ASIC started its ‘Wealth Management Project’, a major project focusing upon the financial advice businesses conducted by ANZ, CBA, NAB, Macquarie, Westpac and AMP. In April 2015, ASIC announced that it was ‘investigating multiple instances of licensees charging clients for financial advice, including annual advice reviews, where the advice was not provided’. ASIC said that it would ‘consider all regulatory options, including enforcement action’ where it found evidence of breaches of the law and that it would ‘look to ensure that advice licensees follow a proper process of customer remediation and reimbursement of fees where such breaches have occurred’.

As events turned out, however, until immediately before the time the Commission began taking evidence, ASIC had undertaken some investigations and had pursued remediation, but had taken no enforcement action. Rather, as Mr Kell said, ‘most of ASIC’s work in the project had focused on remediation’. And it was not until a few days before the hearings began that ASIC announced first, that it had agreed that ANZ would give an enforceable undertaking and then, a few days later, that it had agreed that two of CBA’s financial advice licensees [CFPL and Bankwest Financial Advice], would give an enforceable undertaking in relation to the charging of fees for no service.

In October 2016, ASIC reported that AMP, ANZ, CBA and NAB had all identified systemic  issues in relation to the charging of ongoing service fees; the report also revealed that, as at 2016, compensation was estimated to be more than $178 million in respect of about 200,000 customers, and that about $23.7 million and had been paid, or agreed to be paid to over 27,000 customers. Between August 2016 and January 2018, the total compensation paid or agreed to be paid and the number of customers affected increased markedly, to the figures given by Mr Kell in his evidence: more than $216 million and more than 305,000.

issues in relation to the charging of ongoing service fees; the report also revealed that, as at 2016, compensation was estimated to be more than $178 million in respect of about 200,000 customers, and that about $23.7 million and had been paid, or agreed to be paid to over 27,000 customers. Between August 2016 and January 2018, the total compensation paid or agreed to be paid and the number of customers affected increased markedly, to the figures given by Mr Kell in his evidence: more than $216 million and more than 305,000.

And, contrary to the tenor of ASIC’s 2016 report, the evidence to the Commission showed that there had been some significant systemic failures after the FoFA reforms. The most notable of those failures examined in evidence related to AMP and its conduct of continuing to charge fees to clients whose advisers had sold their businesses to AMP as the ‘buyer of last resort’. No doubt the advice licensees would say that undertaking remediation programs for clients who had been charged fees for no services constituted their acknowledgment of wrongdoing. But there has been no formal public condemnation of what occurred.

The only formal and public steps that have been taken with respect to this issue, beyond ASIC issuing its reports and Press Releases, was ASIC’s acceptance, very soon before the Commission began its hearings, of the enforceable undertakings. The undertakings went no further than to record ASIC’s ‘concerns’ and that the relevant entities acknowledge that those concerns are ‘reasonably held’. This is well short of a full and frank acknowledgment by the entities that what they had done was wrong. No doubt ANZ and CBA would point to their having each agreed to ‘make a community benefit payment’ of $3 million. But if paying that negotiated amount is to be understood as some form of penalty marking the public denunciation of the licensees’ conduct, it seems small compared with the amounts of money that the remediation programs show have been needed to make good the damage done to clients: nearly $90 million in the case of the CBA licensees and nearly $50 million in ANZ’s case.

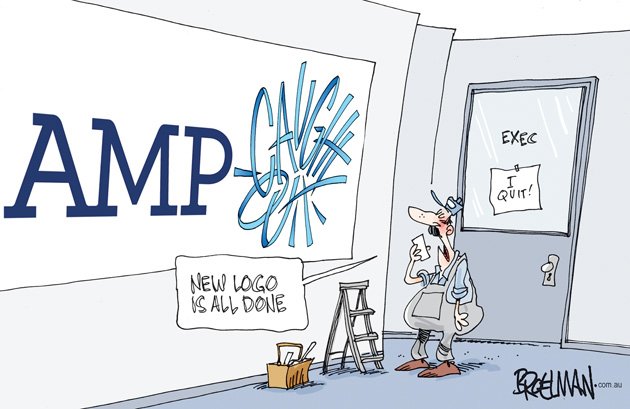

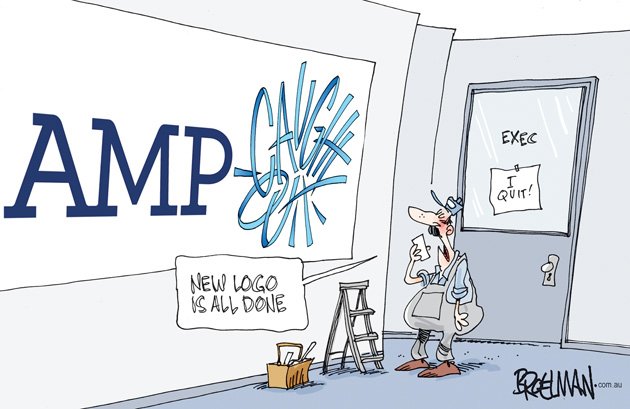

The results recorded in ASIC’s report were obtained by examining the files of 10 advice licensees associated with the five largest entities: AMP, ANZ, CBA, NAB, and Westpac. They are, therefore, results based on the work of advisers associated with the largest entities that may, because of their size, be assumed to be the best-resourced. Craig Meller resigned as CEO after it was revealed that AMP charged clients for financial advice which was not provided, and misled ASIC on numerous occasions. More than $1 billion in market value was stripped from AMP shares as news of the company’s failings were revealed. In the wake of revelations at the banking royal commission and his resignation from AMP, Meller resigned as a financial services adviser to the Turnbull government. A week later, Catherine Brenner, the chair resigned . Directors Vanessa Wallace and Holly Kramer announced they would not be seeking re-election, in response to an imminent protest vote organised by the shareholders in the aftermath of the revelations. Patty Akopiantz also announced she would be resigning at the end of the year.

They are results that demonstrate the validity of a basic observation of the world: that the choice between interest and duty is resolved, more often than not, in favour of self-interest. And they are results that, on their face, deny a fundamental premise for the legislative reforms: that conflicts of interest can be ‘managed’ by saying to advisers, ‘prefer the client’s interests to your own’. Experience [too often, hard and bitter experience] shows that conflicts cannot be ‘managed’ by saying, ‘Be good. Do the right thing’. People rapidly persuade themselves that what suits them is what is right. And people can and will do that even when doing so harms the person for whom they are acting.

A response to an article by David Malone, EO of the Master Builders NT published in the NT News on Wednesday Oct 10/2018.

A response to an article by David Malone, EO of the Master Builders NT published in the NT News on Wednesday Oct 10/2018.

By the time of the Murray Inquiry, the ‘one stop shop’ model was well established in the market. The report observed that the high concentration and steadily increasing vertical integration in some sectors had the potential to limit the benefits of competition. While the report did not express a view as to the merits of vertical integration, the Murray Inquiry recommended ways in which to make ownership and alignment more transparent. It did, however, note that the Global Financial Crisis had exposed ‘significant numbers of Australian consumers holding financial products that did not suit their needs and circumstances’ and that there were ‘significant problems relating to shortcomings in disclosure and financial advice’.

By the time of the Murray Inquiry, the ‘one stop shop’ model was well established in the market. The report observed that the high concentration and steadily increasing vertical integration in some sectors had the potential to limit the benefits of competition. While the report did not express a view as to the merits of vertical integration, the Murray Inquiry recommended ways in which to make ownership and alignment more transparent. It did, however, note that the Global Financial Crisis had exposed ‘significant numbers of Australian consumers holding financial products that did not suit their needs and circumstances’ and that there were ‘significant problems relating to shortcomings in disclosure and financial advice’.

The nature and extent of the ‘fees for no service’ issue was described in the evidence of Mr Kell, Deputy Chair of ASIC. As at 2018, AMP, ANZ, CBA, NAB and Westpac had paid, or agreed to pay, to almost 306,000 customers, combined compensation of more than $216 million. Three of those entities, ANZ, CBA and NAB, had reported to ASIC that they estimated that further compensation of at least $2.5 million would be paid.

The nature and extent of the ‘fees for no service’ issue was described in the evidence of Mr Kell, Deputy Chair of ASIC. As at 2018, AMP, ANZ, CBA, NAB and Westpac had paid, or agreed to pay, to almost 306,000 customers, combined compensation of more than $216 million. Three of those entities, ANZ, CBA and NAB, had reported to ASIC that they estimated that further compensation of at least $2.5 million would be paid. issues in relation to the charging of ongoing service fees; the report also revealed that, as at 2016, compensation was estimated to be more than $178 million in respect of about 200,000 customers, and that about $23.7 million and had been paid, or agreed to be paid to over 27,000 customers. Between August 2016 and January 2018, the total compensation paid or agreed to be paid and the number of customers affected increased markedly, to the figures given by Mr Kell in his evidence: more than $216 million and more than 305,000.

issues in relation to the charging of ongoing service fees; the report also revealed that, as at 2016, compensation was estimated to be more than $178 million in respect of about 200,000 customers, and that about $23.7 million and had been paid, or agreed to be paid to over 27,000 customers. Between August 2016 and January 2018, the total compensation paid or agreed to be paid and the number of customers affected increased markedly, to the figures given by Mr Kell in his evidence: more than $216 million and more than 305,000.