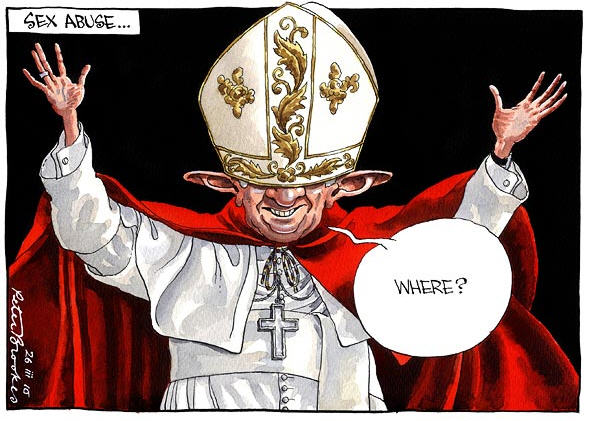

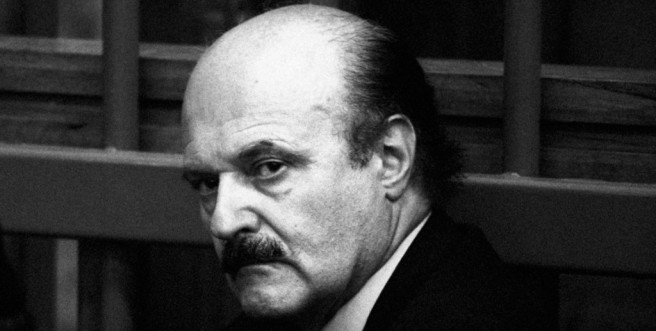

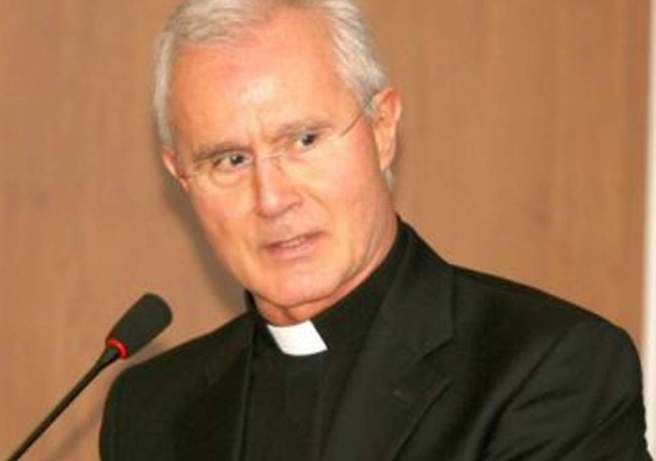

Spare a thought for George Pell, cardinal and once Obersturmbannführer of the Catholic Church Secretariat for the Economy. In December 2018, it was reported that Pell and two others were removed from his role, with effect from late October 2018. This may have had something to do with the court case that was decided in Australia, but nobody was supposed to know due to a suppression order. So he has obviously been deleted from the Pope’s Xmas card list. Pell supported Pope John Paul II’s view that the ordination of women as priests is impossible according to the church’s divine constitution and has also expressed his opinion that abandoning the tradition of clerical celibacy would be a “serious blunder”. Not a great hit with the feminists, unlikely to be welcomed into the arms of those who think celibacy is a medieval perversion.

He has never been a favorite of the Alphabet Set because in 1990, he stated publicly that while he recognised that homosexuality existed, such activity was nevertheless wrong and “for the good of society it should not be encouraged.” He has also expressed his belief that suicide linked to homophobia was a valid reason to discourage recognition of a gay identity, arguing that “Homosexual activity is a much greater health hazard than smoking.” He opposed Australian legislation in 2006 that would have permitted gay couples to adopt children. In 2007, Pell said that discrimination against people that are gay was not comparable to that against racial minorities. No pressies from anyone who bats for both sides.

Pell was one of the electors who participated in the 2005 papal conclave that selected Pope Benedict XVI. It has been suggested that Pell served as campaign manager behind Benedict’s election. While there was speculation in the Australian media that he had an outside chance of becoming Pope himself, international commentary did not mention Pell as a contender. However, Pell was mentioned as a possible successor to Benedict XVI as head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. For those who were not aware, the precursor to the Congregation, run by the Benedictines, was called the Inquisition. He had the unmitigated gall to institute new guidelines for family members speaking at funerals. He said that, “on not a few occasions, inappropriate remarks glossing over the deceased’s proclivities [drinking prowess, romantic conquests etc.] or about attacking the moral teachings of the Church have been made at funeral Masses.” Pell’s guidelines make it clear that the eulogy must never replace the celebrant’s homily, which should focus on the scripture readings selected, God’s compassion, and the resurrection of Jesus. No matter that the celebrant had no knowledge of the deceased’s activities outside the church. So he has probably pissed off a lot of Irish in the congregation.

Pell was the only cardinal from Oceania to take part in the 2013 papal conclave. Following the election of Pope Francis, [the first Jesuit pope, unexpected because of the tense relations between the Society of Jesus and the Holy See; he is the first from the Americas, the first from the Southern Hemisphere and some say the first non-European pope, but he is actually the 11th, the previous was Gregory III from Syria, who died in 741], Pell was one of eight members appointed to advise the Pope on how to reform the Catholic Church. He was appointed the first prefect of the newly created Secretariat for the Economy. In this role, Pell was responsible for the annual budget of the Holy See and the Vatican. In order to consolidate his financial hegemony it was announced that Pell had the Ordinary Section of Administration of the Patrimony of the Apostolic See (APSA) transferred to the Secretariat for the Economy, claiming that this was an important step to enable his committee to exercise its responsibilities of economic control and vigilance over the agencies of the Holy See. It was also announced that remaining staff of APSA would begin to focus exclusively on its role as a treasury for the Holy See and the Vatican City State.

The Secretariat for the Economy distributed a handbook to all Vatican offices outlining financial management policies.

“The purpose of the manual is very simple”, said Pell, “it brings Financial Management practices in line with international standards and will help all Entities and Administrations of the Holy See and the Vatican City State prepare financial reports in a consistent and transparent manner. The Secretariat for the Economy will provide training and support to the Vatican/Holy See offices to help implement the new policies.” However, Cardinal Francesco Coccopalmerio questioned the scope of the authority given to the Secretariat for the Economy and to Pell himself. These questions involved not the demand for transparency in all financial operations, but the consolidation of management.

In his 2014 appearance before the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, Pell likened the Catholic Church to a trucking company: “If the truck driver picks up some lady and then molests her, I don’t think it’s appropriate, because it is contrary to the policy, for the ownership, the leadership of that company to be held responsible.”

Michael Bradley, writing in his weekly column for ABC News, said:

“Yes, it was mind-blowingly insensitive to draw that analogy and to so blithely refer to ‘some lady’. But there was a much bigger hole. In the world according to Pell, if the Catholic Church has a policy that tells its priests not to rape children then, if they still do so, the Church cannot be held accountable.”

Pell’s health was in the news in 2015 when it was judged serious enough to prevent air travel from Italy to Australia to appear before the Royal Commission. He was expected to be well enough to travel in February 2016. However, in the end he testified from a hotel in Rome through a video link up. Ballarat based state MP Sharon Knight said, after hearing that Pell would not return to Australia to appear before the commission due to an undisclosed heart condition by saying “if we do ever see you back in this country, then we will know that everything you have said about your health – everything that you have said to avoid personally appearing at the hearings – is an absolute sham.”

Pell is known as a climate change denier, and aroused criticism from Australian Senator Christine Milne of the Greens political party with the following comment in his 2006 Legatus Summit speech:

Some of the hysteric and extreme claims about global warming are also a symptom of pagan emptiness, of Western fear when confronted by the immense and basically uncontrollable forces of nature. Belief in a benign God who is master of the universe has a steadying psychological effect, although it is no guarantee of Utopia, no guarantee that the continuing climate and geographic changes will be benign. In the past pagans sacrificed animals and even humans in vain attempts to placate capricious and cruel gods. Today they demand a reduction in carbon dioxide emissions.

….. and therefore unlikely to be well thought of by the Greens and pagans.

Bishop George Browning, who told the Anglican Church of Australia’s general synod that Pell was out of touch with the Catholic Church as well as with the general community, Pell stated:

Radical environmentalists are more than up to the task of moralising their own agenda and imposing it on people through fear. They don’t need church leaders to help them with this, although it is a very effective way of further muting Christian witness. Church leaders in particular should be allergic to nonsense….. I am certainly skeptical about extravagant claims of impending man-made climatic catastrophes. Uncertainties on climate change abound … my task as a Christian leader is to engage with reality, to contribute to debate on important issues, to open people’s minds, and to point out when the emperor is wearing few or no clothes.

When it comes to those who refuse to even acknowledge the existence of the emperor, let alone whether he is clothed or not, the Catholic Church would be at the head of the queue.

From 590 to 1517, the Roman Church dominated the western world it controlled religion, philosophy, morals, politics, art and education. This was the dark ages for true Christianity. The vital religious doctrines had almost disappeared, and with the neglect of true doctrine came the passing of life and light that constitutes the worship of the One True God as declared in Christ. The Roman Catholic Church was theologically sick and its theology led to atrocious corruptions. Rome had seriously departed from the teaching of the Bible and was engrossed in real heresy.

While Infallibility of the Pope was not an officially declared dogma of the Roman Church [it became official dogma in 1870], it was an assumed fact. As early as 590, Gregory the Great called himself ‘the servant of servants,’ believing that he was supreme among all bishops. Another pope, Hildebrand or Gregory VII, held that, as vicar of Christ and representative of Peter, he could give or take empires. Everyone from the lowest peasant to the highest ruler was to recognize him as Christ’s representative on earth and supreme ruler over all religious and political matters. Boniface VII, said, “We declare, state, define and pronounce that for every human creature to be subject to the Roman pope is altogether necessary for salvation”

Rome taught that all who did not acknowledge the pope as God’s representative on earth and the Roman Catholic Church as the only true church were damned. Salvation was confined within the teachings of the Roman Church. Every person who disagreed with the Roman Church was in line for excommunication, the loss of one’s soul. Augustinian theology was lost or badly neglected. Rome had accepted almost in totality the teaching of Pelagius that it had formerly repudiated. Salvation was not caused by God’s grace through a supernatural new birth, but by assent to Roman Catholic dogma and practice. Faith was not trust in Christ for salvation, but submission to the church. Salvation was not by grace through faith in Christ alone, but by faith in the church and good works prescribed by the church. Practically speaking, ‘good works’ consisted of mere external obedience to the church, and did not necessarily flow from a life of faith in Christ. The Roman Catholic Church stressed external actions, legal observance and penitential works.

When the doctrine that man could attain a state of perfect sanctification was proclaimed, it affirmed that the merits of saints and martyrs might be applied to the Church. A peculiar power was attributed to their intercession. Prayers were made to them; their aid was invoked in all the sorrows of life; and a real idolatry thus supplanted the adoration of the living and true God. The doctrine of sinless perfectionism strengthened the position of the Roman hierarchy. The clergy were thought to be more holy than the average people. Being more holy, they were special channels of the grace of God. Thus, the clergy had the authority from God to dispense God’s grace.

“Souls thirsting for pardon were no more to look to heaven, but to the Church, and above all to its pretended head. To these blinded souls the Roman pontiff was God. Hence the greatness of the popes – hence unutterable abuses.”

Great importance was soon attached to external marks of repentance — to tears, fasting, and mortification of the flesh; and inward regeneration of the heart, which alone constitutes a real conversion, was forgotten. As confession and penance are easier than the extirpation of sin and the abandonment of vice, many ceased contending against the lusts of the flesh, and preferred gratifying them at the expense of a few mortifications. Men were required to fast, to go barefoot, to wear no linen, etc.; to quit their homes and their native land for distant countries; or to renounce the world and embrace a monastic life.

Great importance was soon attached to external marks of repentance — to tears, fasting, and mortification of the flesh; and inward regeneration of the heart, which alone constitutes a real conversion, was forgotten. As confession and penance are easier than the extirpation of sin and the abandonment of vice, many ceased contending against the lusts of the flesh, and preferred gratifying them at the expense of a few mortifications. Men were required to fast, to go barefoot, to wear no linen, etc.; to quit their homes and their native land for distant countries; or to renounce the world and embrace a monastic life.

In the eleventh century voluntary flagellations were added to these practices; somewhat later they become quite a mania in Italy. Nobles and peasants, old and young, even children of five years of age, whose only covering was a cloth round the middle, went in pairs, by thousands, and tens of thousands, through the towns and villages, visiting the churches in the depth of winter. Armed with scourges, they flogged each other without pity, and the streets resounded with cries and groans that drew tears from all who heard them. Indulgences were a system of exchange whereby the priests employed their special rapport with God to perform certain religious acts for laymen. For a price, Clergy would pray, fast and read scripture for a person. This was later developed into buying

up time one might have to spend in purgatory.

“Incest, if not detected, was to cost five groats; and six, if it was known. There was a stated price for murder, infanticide, adultery, perjury, burglary, etc. O disgrace of Rome!’ exclaims Claude d’Espence, a Roman divine: and we may add, O disgrace of human nature! for we can utter no reproach against Rome that does not recoil on man himself. Rome is human nature exalted in some of its worst propensities” [D’aubigne].

Since the clergy through the church were dispensers of God’s grace, they also had the authority to forgive sins. Private confession was abandoned for auricular confession to the priest.

Celibacy for clergy became Roman Church law in 1079. This mandate tempted all kinds of immorality. The abodes of the clergy were often dens of corruption. It was a common sight to see priests frequenting the taverns, gambling, and having orgies with quarrels and blasphemy. Many of the clergy kept mistresses, and convents became houses of ill fame. In many places the people were delighted at seeing a priest keep a mistress, that the married women might be safe from his seductions. Indulgences were looked upon by the common man as a license to sin, for men could buy their forgiveness.

“In many places the priest paid the bishop a regular tax for the women with whom he lived, and for each child he had by her. A German bishop said publicly one day, at a great entertainment, that in one year eleven thousand priests had presented themselves before him for that purpose. It is Erasmus who relates this” (D’aubigne).

Many of the clergy came to their offices through political maneuvering. In a country parish one person called the clergy “miserable wretches . . . previously raised from beggary, and who had been cooks, musicians, huntsmen, stable boys and even worse.” Clergy no longer had to learn and teach the Scriptures, for the church told them what to do. Even the superior clergymen were sunk in great ignorance in spiritual matters. They had secular learning, but knew very little of the Bible.

“A bishop of Dunfeld congratulated himself on having never learned either Greek or Hebrew. The monks asserted that all heresies arose from those two languages, and particularly from the Greek. The New Testament, said one of them, is a book full of serpents and thorns. Greek, a new and recently invented language, and we must be upon our guard against it. As for Hebrew, my dear brethren, it is certain that all who learn it immediately become Jews.”

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the government system of the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy. It started in 12th-century France to combat religious dissent, in particular the Cathars and the Waldensians. Other groups investigated later included the Spiritual Franciscans, the followers of Jan Hus and the Beguines. Beginning in the 1250s, inquisitors were generally chosen from members of the Dominican Order, replacing the earlier practice of using local clergy as judges.

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the government system of the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy. It started in 12th-century France to combat religious dissent, in particular the Cathars and the Waldensians. Other groups investigated later included the Spiritual Franciscans, the followers of Jan Hus and the Beguines. Beginning in the 1250s, inquisitors were generally chosen from members of the Dominican Order, replacing the earlier practice of using local clergy as judges.

During the Late Middle Ages and the early Renaissance, the concept and scope of the Inquisition significantly expanded in response to the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation. It expanded to other countries, resulting in the Spanish Inquisition and Portuguese Inquisition that operated inquisitorial courts throughout their empires in Africa, Asia, and the Americas [resulting in the Peruvian and Mexican Inquisition]. These inquisitions focused particularly on the issue of Jewish anusim and Muslim converts to Catholicism, partly because these groups were more numerous in Iberia than in many other parts of Europe, and partly to the assumption that they had secretly reverted to their previous religions.

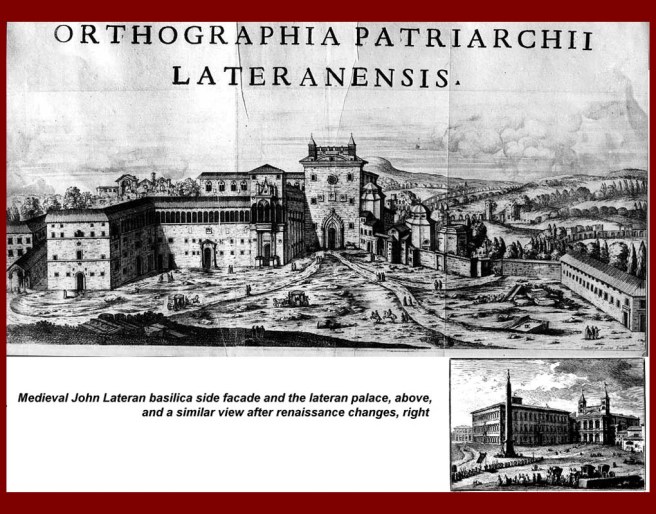

With the exception of the Papal States, the institution of the Inquisition was abolished in the early 19th century, after the Napoleonic Wars in Europe and the Spanish American wars of independence in the Americas. The institution survived as part of the Roman Curia, but in 1908 it was renamed the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office. In 1965 it became the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. From 1378-1417 there were three simultaneous popes, each claiming to be the true pope: Urban VII, an Italian; Clement VII, a Frenchman; and a third pope elected by the Council of Pisa. For several years there were three popes anathematizing and excommunicating one another. Simony, the practice of giving or obtaining an appointment to a church office for money, was a common practice in the Middle Ages, even in the obtaining of the office of pope.

The Catholic Church was officially recognized by Emperor Constantine in the early 4th century. With this recognition the religious leaders, soon to be known as the clergy gradually evolved into a separate, privileged class, the most exalted members of which were the bishops. Although celibacy did not become a universally mandated state for clerics of the western Church until the 2nd Lateran Council, 1139, various church leaders began to advocate it by the 4th century. The earliest recorded church legislation is from the council of Elvira [Spain, 306 AD]. Half of the canons passed dealt with sexual behavior of one kind or another and included penalties assessed for clerics who committed adultery or fornication. Though it did not make specific mention of homosexual activities by the clergy, this early Council reflected the church’s official attitude toward same-sex relationships: men who had sex with young boys were deprived of communion even on their deathbed.

The Catholic Church is organized in geographic regions known as dioceses, from a Greek word meaning a group. The head of a diocese has traditionally been a bishop. Early church legislation was passed by individual bishops for their own territory but the more important legislation with lasting historical impact, was that passed by groups of bishops who gathered at periodic meetings known as councils or synods which were generally named after the place where they occurred. Laws were passed throughout the Christian world. These laws, whether the product of individual bishops or groups, did not need the approval of the papacy.

Although the pope had been respected as the first among bishops from the earliest years of Christianity, the centralization of power was not evident until the middle ages during which time several popes gradually reserved various powers to themselves. By the 9th century collections of the growing mass of legislation began to appear. Several of the more prominent and complete collections have survived as essential sources for the study of the development not only of church law but of the Christian life in general. The first truly systematic collection was produced by the monk Gratian in 1140. Known as Gratian’s Decree it consisted of a wide spectrum of texts arranged in a dialectic method with Gratian’s own opinions added. Though never officially approved, Gratian’s decree became the most important resource for the history of Canon Law. Following the medieval period the major legislative sources were the popes themselves and the general or ecumenical councils, the most recent of which was Vatican II (1962-65).

The practice of individual confession of sins to a priest started in the Irish monasteries in the latter sixth century. With individual confession came the Penitential Books, another valuable source for church history. These were unofficial manuals drawn up by various monks to assist in their private counseling with penitents in confession. These books listed the various and sundry acts which the church considered sinful and provided guidance on the acceptable penance to be imposed. The Penitentials provide a vivid glimpse into the darker side of Christian life at the time. Though it is not known exactly how many such books were written, the more prominent ones have been preserved, studied and translated. Several of these refer to sexual crimes committed by clerics against young boys and girls. The Penitential of Bede [England, 8th century] advises that clerics who commit sodomy with young boys be given increasingly severe penances commensurate with their rank, the higher ranking bishops receiving harsher penalties. The regularity with which mention is made of clergy sex crimes shows that the problem was not isolated, was known in the community and was treated more severely than similar acts committed by lay men. The Penitential Books were in use from the mid 6th century to the mid 12th century.

The most dramatic and explicit condemnation of forbidden clergy sexual activity was the Book of Gomorrah of St. Peter Damian, completed in 1051. The author was a Benedictine monk appointed archbishop and later cardinal by the reigning pope. Peter Damian was also a dedicated Church reformer who lived in a society wherein clerical decadence was not only widespread and publicly known, but generally accepted as the norm. His work, the circumstances that prompted it and the reaction of the reigning pope [Leo IX] are a prophetic reflection of the contemporary situation. He begins by singling out superiors who, prompted by excessive and misplaced piety, fail to exclude sodomites. He asserts that those given to unclean acts not be ordained or, if they are already ordained, be dismissed from Holy Orders. He holds special contempt for those who defile men or boys who come to them for confession. Likewise he condemns clerics who administer the sacrament of penance to their victims. His final chapter is an appeal to Leo IX to take action.

The pope’s response is an example of inaction similar to that of contemporary church leaders. Pope Leo praised Peter Damian and verified the truth of his findings and recommendations. Yet he considerably softened the reformer’s urging that decisive action be taken to root out offenders from the ranks of the clergy. The pope decided to exclude only those who had offended repeatedly and over a long period of time. Although Peter Damian had paid significant attention to the impact of the offending clerics on their victims, the Pope made no mention of this but focused only on the sinfulness of the clerics and their need to repent.

Medieval scholars attest that clerical concubinage was commonplace. Adultery, casual sex with unmarried women and homosexual relationships were rampant. Gratian devoted entire sections to disciplinary legislation which attempted to curb all of these vices. He demanded that the punishment for sexual transgressions be more severe for clerics than for lay men. His treatment of same-sex activities was less extensive than that of other celibacy violations, yet his attitude is evident because he cited the ancient Roman law opinion that stuprum pueri, the sexual violation of young boys, be punished by death. From the 4th century to the end of the medieval period it is clear that violations of clerical celibacy were commonplace, expected by the laity and highly resistant to official disciplinary attempts to curb and eliminate them. Referring to concubinage for example, one noted scholar said: From the repeated strictures against clerical incontinence by provincial synods of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, one may surmise that celibacy remained a remote and only defectively realized ideal in the Latin West. In England, particularly in the north, concubinage continued to be customary; it was frequent in France, Spain and Norway.

The Protestant Reformation of the 16th century was sustained by much more than the controversy over the sale of indulgences. Luther and the other major reformers such as Zwingli and Calvin, all rejected mandatory celibacy. The rejection was motivated in great part by what the reformers saw as widespread evidence that clerics of all ranks commonly violated the obligations with women, men and young boys. In reference to life in the monasteries on the eve of the 16th century Protestant Reformation, Abbott says that the monks’ “lapses” with women, handsome boys and each other…became so commonplace that they could not be considered lapses but ways of life for entire communities.” Up to this time the Church’s leaders continued to advocate the long-standing remedies of legislation, spiritual penalties, physical penalties and warnings, none of which worked. Living in the midst of a clerical world of non-celibate behavior, the reformers believed that this supposedly celibate world caused moral corruption: The sexual habits of the Roman Catholic clergy, according to reformers, were a sewer of iniquity, a scandal to the laity, and a threat of damnation to the clergy themselves.

In spite of attempts to propagate revisionist versions of the Reformation, the Church’s primary reaction, the ecumenical Council of Trent (1545-1563), was itself proof of the deeply entrenched and wide-ranging corruption in the Church. Secular princes had urged a reforming council but the popes resisted until 1545 when Pope Paul II summoned one to be held in the Italian city of Trento. The council met in 25 sessions with several periods of adjournment. It ended in 1563 after session 25 when most of the major reforms were enacted. The reaffirmation of clerical celibacy did not conclude without strong opposition from a significant number of bishops who argued that mandatory celibacy was simply not working and accomplished no more than denying priests’ wives and children a share in their estates. A canon was proposed which would have permitted marriage for clergy but this was rejected and mandatory celibacy re-enforced. The canon upholding celibacy was followed by one which extolled it as superior to marriage.

In spite of the reforming legislation and the establishment of mandatory training, education and formation for priests, the bishops at Trent were no more successful at curbing celibacy violations than their predecessors. Illicit sex with women, men and young boys continued but for a time were much less obvious. By 1566, in the first year of his pontificate, Pope Pius V (1566-72) recognized a need to publicly attack clerical sodomy. The constitution Romani Pontifices promulgated legislation against a variety of actions and practices, including the ‘crime against nature.’ This short canon condemned all who committed this crime and prescribed that they be handed over to secular authorities for punishment.

Summarizing the medieval period, it is clear that the bishops were not as preoccupied with secrecy as they are today. Clergy sexual abuse of all kinds was apparently well known by the public, the clergy and secular law enforcement authorities. There was a constant stream of disciplinary legislation from the church but none of it was successful in changing clergy behavior. In spite of a millennium of failure, the popes and bishops never gave serious thought to the viability of mandatory celibacy. The variety of spiritual punishments was joined, in the later period, with severe corporal penalties, inflicted by secular authorities. Finally, and most important, at certain periods, church authorities recognized that the problem was not only dysfunctional clerics, but irresponsible leadership.

In 1962 Pope John XXIII approved the publication of renewed special procedural norms. Unlike all previous papal legislation on this subject, this document was buried in the deepest secrecy. Although it was promulgated in the ordinary manner and then printed and distributed by the Vatican press, it was never publicized in the official Vatican legal bulletin, the Acta Apostolicae Sedis. The document was sent to all bishops in the world. It is preceded by an order whereby the document is to be kept in the secret archives and not published nor commented upon by anyone. No explicit reason was given for this unusual secrecy nor is any justification given for the document or some of the surprising changes contained therein.

The 1962 document is significant because it reflects the church’s urgent desire to maintain the highest degree of secrecy and strictest degree of security about the worst sexual crimes perpetrated by clerics. The document does not include any background information about why it was issued nor is there any reasoning available for the imposition of extreme secrecy and the inclusion of the crimes in Title V. One can only presume that cases or concerns had been brought to the attention of the Vatican authorities which prompted the decree. Since the archives of the Holy Office, now known as the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, are closed to outside scrutiny it is impossible to determine the number of cases referred to it between 1962 and the present. The other factor impeding a study of cases is the prohibition of local dioceses from ever revealing the very existence of cases much less the relevant facts.

The public exposure of clergy sexual abuse of youth which began in the mid-eighties was mistakenly believed by many to be a new phenomenon which of course it is not. In spite of a series of high profile cases from around the world the Vatican issued no disciplinary documents until 2001. Although the pope had made several statements about clergy sexual abuse this was the first attempt by the Vatican to take concrete steps to contain the problem. The document, which is a set of special procedural norms, is not exclusively about sex abuse although that is the predominant theme. It is about the processing of certain crimes considered by the Vatican authorities to be so serious that prosecution of them is reserved to the Vatican itself.

In spite of claims to the contrary, the canonical history of the Catholic Church clearly reflects a consistent pattern of awareness that celibate clergy regularly violated their obligations in a variety of ways. The fact of clergy abuse with members of the same sex, with young people and with women is fully documented. At certain periods of church history clergy sexual abuse was publicly known and publicly acknowledged by church leaders. From the late 19th century into the early 21st century the church’s leadership has adopted a position of secrecy and silence. They have denied the predictability of clergy sexual abuse in one form or another and have claimed that this is a phenomenon new to the post-Vatican II era. The recently published reports of the Bishops’ National Review Board and John Jay College Survey have confirmed the fact of known clergy sexual abuse since the 1950’s and the church leadership’s consistent mishandling of individual cases.

The bishops have, at various times, claimed that they were unaware of the serious nature of clergy sexual abuse and unaware of the impact on victims. This claim is easily offset by the historical evidence. Through the centuries the church has repeatedly condemned clergy sexual abuse, particularly same-sex abuse. The very texts of many of the laws and official statements show that this form of sexual activity was considered harmful to the victims, to society and to the Catholic community. Church leaders may not have been aware of the scientific nature of the different sexual disorders nor the clinical descriptions of the emotional and psychological impact on victims, but they cannot claim ignorance of the fact that such behavior was destructive in effect and criminal in nature.

Over 50 billion dollars in securities. Gold reserves that exceed those of industrialized nations. Real estate holdings that equal the total area of many countries. Opulent palaces containing the world’s greatest art treasures. These are some of the riches of the Roman Catholic Church. Yet in 1929 the Vatican was destitute. Pius XI, living in a damaged, leaky, pigeon-infested Lateran Palace, heard rats scurrying through the walls, and he worried about how he would pay for basic repairs to unclog the overburdened sewer lines and update the antiquated heating system. How did the Church manage in less than seventy-five years such an incredible reversal of fortune?

The turnaround began on February 11, 1929, with the signing of the Lateran Treaty between the Vatican and fascist leader Benito Mussolini. Through this deal Mussolini gained the support of the Italian populace, who at the time followed the lead of the Church. In return, the Church received, among other benefits, a payment of $90 million, sovereign status for the Vatican, tax-free property rights, and guaranteed salaries for all priests throughout the country from the Italian government. With the stroke of a pen the pope had solved the Vatican’s budgetary woes practically overnight, yet he also put a great religious institution in league with some of the darkest forces of the 20th century.

Evidence of the Church’s morally questionable financial dealings with sinister organizations over seven decades suggests the Vatican accrued enormous wealth during the Great Depression by investing in Mussolini’s government, engineered a connection between Nazi gold and the Vatican Bank, increased the vast range of Church holdings in the postwar boom period, benefited from Paul VI’s appointment of Mafia chieftain Michele Sindona as the Vatican banker, and banked the proceeds of a billion-dollar counterfeit stock fraud uncovered by Interpol and the FBI. The Ambrosiano Affair called “the greatest financial scandal of the 20th Century” by the New York Times, included the mysterious death of John Paul I, and suggested the Vatican profited from an international drug ring operating out of Gdansk, Poland.

The present whereabouts of the Nazi gold that disappeared into European banking institutions in 1945 has been the subject of several books, conspiracy theories, and a civil suit brought in 2001 against the Vatican Bank, the Franciscan Order and other defendants. That the Nazi regime maintained a policy of looting the assets of its victims to finance its war, collecting the looted assets in central depositories, and that it occasionally transferred gold to banks outside the Third Reich in return for currency, have been well documented since the 1950s. The identity of individual collaborative institutions and the precise extent of transactions is more open to denial, however. Among Nazi puppet regimes, the Ustasha regime also maintained concentration camps and confiscated the assets of its victims in the campaign of ethnic cleansing to clear ‘Greater Croatia’ of Serbs, Roma, and Jews. Victims’ assets were deposited in the Ustasha Treasury. In 1948, U.S. Army Intelligence reports confirmed that 2,400 kilos of Ustasha stolen gold were moved from the Vatican to one of the Vatican’s numbered Swiss bank accounts. At the time of the collapse of the Ustasha in 1945, Ustasha agents were found at the British-occupied Austro-Swiss border with gold valued at 350 million Swiss francs. Intelligence reports also suggest that more than 200 million Swiss francs were eventually transferred to Vatican City and the IOR with the assistance of Roman Catholic clergy and the Franciscan Order.

The Banco Ambrosiano was founded in Milan in 1896 by Giuseppe Tovini, and was named after Saint Ambrose, the fourth century archbishop of the city. Tovini’s purpose was to create a Catholic bank as a counterbalance to Italy’s lay banks, and its goals were serving moral organisations, pious works, and religious bodies set up for charitable aims. The bank came to be known as the priests bank. In the 1960s, the bank began to expand its business, opening a holding company in Luxembourg which came to be known as Banco Ambrosiano Holding. This was under the direction of Carlo Canesi, then a senior manager, and from 1965 chairman. His deputy was Roberto Calvi.

In 1971, Calvi became general manager, and in 1975 he was appointed chairman. Calvi expanded Ambrosiano’s interests further; these included creating a number of off-shore companies in the Bahamas and South America; a controlling interest in the Banca Cattolica del Veneto; and funds for the publishing house Rizzoli to finance the Corriere della Sera newspaper, giving Calvi control behind the scenes for the benefit of his associates in the P2 masonic lodge. Calvi also involved the Istituto per le Opere di Religione [IOR], in his dealings, and was close to Bishop Paul Marcinkus, the bank’s chairman. Ambrosiano provided funds for political parties in Italy, and for both the Somoza dictatorship in Nicaragua and its Sandinista opposition. Calvi used his complex network of overseas banks and companies to move money out of Italy, to inflate share prices, and to secure massive unsecured loans. In 1978, the Bank of Italy produced a report on Ambrosiano that predicted future disaster and led to criminal investigations. However, soon afterward the investigating Milanese magistrate was assassinated by a left-wing terrorist group, while the Bank of Italy official who superintended the inspection, Mario Sarcinelli, found himself imprisoned.

When the Holy See, whose tax-exempt status on income from Italian investments was revoked in 1968, decided to diversify its holdings, it employed as financial adviser Michele Sindona. Once among the country’s most powerful businessmen, subsequent investigations into his business affairs brought to light questionable associations with the Mafia as well as the secret P2, a bogus Masonic lodge that the Italian Parliament branded as a subversive organization. The 1974 failure of Sindona’s Franklin National Bank and the subsequent collapse of his financial empire, into which he had channeled part of the Holy See’s investments, entailed losses for the Vatican estimated by one source at 35 billion Italian lire.

In 1982, a political and financial scandal connected with the collapse of Banco Ambrosiano involved the head of IOR from 1971 to 1989, Archbishop Paul Marcinkus, who allegedly had given letters of patronage on behalf of the IOR in support of the failed bank. In 1987, an Italian court issued a warrant against Marcinkus, whom they accused of being an accessory to fraudulent bankruptcy. Marcinkus evaded arrest by staying inside Vatican City until the warrant was dismissed in 1991, whereupon he returned to his home country, the U.S. Roberto Calvi was convicted of violating Italian currency laws and fled on a false passport to London where he was found murdered under Blackfriars Bridge in London some days after he went missing from Milan. The IOR then a 10% shareholder of Banco Ambrosiano, denied legal responsibility for the Ambrosiano’s downfall but acknowledged moral involvement, and paid US$224 million to creditors.

On 10 June 1982, Calvi went missing from his Rome apartment, having fled the country on a false passport in the name of Gian Roberto Calvini, fleeing initially to Venice. From there, he apparently hired a private plane to London via Zurich. A postal clerk crossing Blackfriars Bridge noticed Calvi’s body hanging from the scaffolding beneath. Calvi’s clothing was stuffed with bricks, and he was carrying around US$15,000 worth of cash in three different currencies. Calvi was a member of Licio Gelli’s masonic lodge, Propaganda Due (P2), who referred to themselves as frati neri or black friars. This led to a suggestion in some quarters that Calvi was murdered as a masonic warning because of the symbolism associated with the word Blackfriars.

The day before his body was found, Calvi was stripped of his post at Banco Ambrosiano by the Bank of Italy, and his 55-year-old private secretary, Graziella Corrocher, jumped to her death from a fifth floor window at the bank’s headquarters. Corrocher left behind an angry note condemning the damage that Calvi had done to the bank and its employees. Her death was ruled a suicide.

Calvi’s death was the subject of two coroner’s inquests in the United Kingdom. The first recorded a verdict of suicide in July 1982. The Calvi family then secured the services of George Carman QC. At the second inquest, in July 1983, the jury recorded an open verdict, indicating that the court had been unable to determine the exact cause of death. Calvi’s family maintained that his death had been a murder. In 1991, the Calvi family commissioned the New York-based investigation company Kroll Associates to investigate the circumstances of Calvi’s death. As part of it’s two-year investigation, the company instructed former Home Office forensic scientists, including Angela Gallop, to undertake forensic tests. As a result, it was found that Calvi could not have hanged himself from the scaffolding because the lack of paint and rust on his shoes proved that he had not walked on the scaffolding. In October 1992, the forensic report was submitted to the Home Secretary and the City of London Police, who dismissed it.

Following the exhumation of Calvi’s body in December 1998, an Italian court commissioned a German forensic scientist to repeat the work produced by the forensic team. That report was published in October 2002, ten years after the original, and confirmed the first report. In addition, it said that the injuries to Calvi’s neck were inconsistent with hanging and that he had not touched the bricks found in his pockets. When Calvi’s body was found, the level of the River Thames had receded with the tide, giving the scene the appearance of a suicide by hanging, but at the exact time of his death, the place on the scaffolding where the rope had been tied could have been reached by a person standing in a boat. That had also been the conclusion of a separate report, which also detailed a reconstruction based on Calvi’s last known movements in London and theorized that Calvi had been taken by boat from a point of access to the Thames in West London. Calvi’s life was insured for US$10 million with Unione Italiana. Following the forensic report of 2002, which established that Calvi had been murdered, the policy was finally settled, although around half of the sum was paid to creditors of the Calvi family who incurred considerable costs during their attempts to establish Calvi’s cause of death.

On 28 June 2013, three persons were arrested by the Italian police on suspicion of corruption and fraud. Allegedly, they had planned to smuggle €20 million in cash from Switzerland into Italy. One of the arrested was Monsignore Nunzio Scarano, previously senior accountant at APSA. Subsequently, he was indicted with corruption and slander and set under house arrest. On 21 January 2014, he was further charged with money laundering through IOR accounts in yet another investigation. According to a police statement, millions of euros in false donations from offshore companies had moved through Scarano’s accounts. As news agency Reuters reported, Elena Guarino, the Salerno magistrate who led the investigation, told reporters the Vatican was fully cooperative and gave her much information on Scarano’s bank movements. In January 2016, Scarano was acquitted of allegations of corruption, but was given a two year sentence after being convicted of lesser charges of making false allegations.

In February 2017, A court in Rome convicted two former top Vatican Bank officials Paolo Cipriani and Massimo Tulliof for omissions in communications involving three small transfers. Cipriani was a former Vatican bank director and Tulliof was deputy. They were, however, acquitted of a more serious money laundering charge, which involved $60 million in transfers, and were sentenced to four months and ten days in prison. In 2018, Vatican prosecutors indicted former Vatican Bank President Angelo Caloia, and his attorney, Gabriele Liuzzo, for embezzling $62 million, using a real estate scam, between 2001 and 2006.

The Council of Europe’s financial-evaluation arm Moneyval laid down the law for the Vatican Bank, telling the rather unholy financiers who had been accused of abetting money laundering for years that it isn’t enough to just smoke out suspicious account holders and freeze assets. Instead they said the Vatican Bank, formally known as the Institute for Religious Works, or IOR, needed to start actually prosecuting criminal cases. Two years later, thousands of accounts have been closed or frozen, but Moneyval still isn’t happy. According to its 209-page December 2017 progress report, the Vatican gets good marks for not funding terrorism and for flagging potential illegal behavior. But the holy bank fails once again to actually hold anyone accountable for what are clearly crimes such as fraud, including serious tax evasion, misappropriation and corruption. More curious still, a week before the highly anticipated report was released, the IOR Deputy Director Giulio Mattietti was fired with no advance warning and escorted from his office out of fear he might remove files from his desk.

Mattietti was hired in 2007 by Paolo Cipriani, the former head of the bank who resigned under pressure a few months after Pope Francis was elected in 2013, after a Vatican accountant nicknamed “Monsignor 500” for his penchant for 500-euro notes, was arrested for trying to smuggle $26 million to Switzerland. Mattietti’s removal followed the sacking of a lower-level IOR employee days earlier. The Vatican gives no official reason for either of the firings beyond reforms, but a source close to the bank says the bank employees who were let go may have been whistle-blowers who were alerting officials outside the bank about continuing impropriety. In fact, despite apparently precise record keeping on the part of IOR, Moneyval evaluators still found 69 actions involving 38 customers that were not in accordance with money laundering and fraud standards set forth by the Council of Europe. None of those suspect cases were prosecuted to the fullest extent under the law, and instead investigators point to vague records that imply that the cases were closed.

“Eight money-laundering investigations have been closed formally without any charges, while six additional investigations have been concluded without an indictment for any offense and their formal closure has been requested.”

And therein lies a problem. The bank once had more than 30,000 account holders, including several religious entities and private citizens who maintained accounts worth millions at the hallowed institution, which is tucked safely within the sovereign state of Vatican City. The bank has since closed several high-profile accounts, including many held by diplomatic missions and the consulates to Syria, Iran, and Iraq who moved millions of euros around through vague cash transactions, but it has never been able to shake its troubled past. In June 2017 the Vatican’s prefect of the Secretariat of the Economy, Cardinal George Pell was sent back to Australia to face child sex-abuse charges in early 2018, leaving a notable gap in the pope’s efforts to reform the church’s troubled finances.

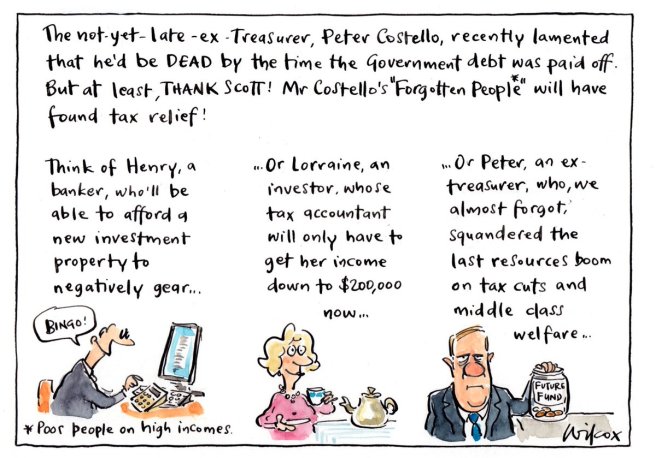

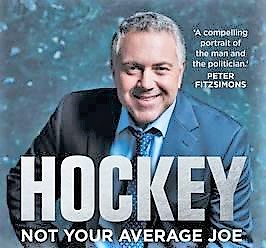

In a 2012 speech, delivered to London’s Institute for Economic affairs, Australia’s now Ambassador to the US, used the podium to rail against the pernicious effect of the welfare safety net, which had been constructed by sleepwalking Western democracies using tax revenue collected disproportionately from hard working folk [that voted for his party]. Some voters had become so used to the state providing healthcare, education and a social safety net that they had come to expect it, Hockey argued. Government spending on these social programs had reached extraordinary levels of GDP, and “people had come to believe that they had a right to a good or service that someone else was paying for. A weak government gives its citizens everything they want, but “a strong government has the will to say ‘No!'” Hockey lectured.

In a 2012 speech, delivered to London’s Institute for Economic affairs, Australia’s now Ambassador to the US, used the podium to rail against the pernicious effect of the welfare safety net, which had been constructed by sleepwalking Western democracies using tax revenue collected disproportionately from hard working folk [that voted for his party]. Some voters had become so used to the state providing healthcare, education and a social safety net that they had come to expect it, Hockey argued. Government spending on these social programs had reached extraordinary levels of GDP, and “people had come to believe that they had a right to a good or service that someone else was paying for. A weak government gives its citizens everything they want, but “a strong government has the will to say ‘No!'” Hockey lectured.

Sure they might seek to minimise their income for tax reasons, but at least they pay their own way, right? They don’t leach off government services. They made their money through hard graft. Except that no one gets that rich without the substantial aid, or in cases of outright corruption, the gift, of public assets – be they land, contracts or the use of infrastructure built by the taxpayer. The super-rich might not be availing themselves of bulk-billing GPs, but they still use airports and roads, hospitals and universities. When some one humbugs them in the street they expect that the police will sanction the perpetrator. And what would the entitlement-busters make of the behaviour of the big banks, who have been accused of mistreating and mischarging customers for years? The very same banks who availed themselves of hefty billions of taxpayer financial support during the Global Financial Crisis?

Sure they might seek to minimise their income for tax reasons, but at least they pay their own way, right? They don’t leach off government services. They made their money through hard graft. Except that no one gets that rich without the substantial aid, or in cases of outright corruption, the gift, of public assets – be they land, contracts or the use of infrastructure built by the taxpayer. The super-rich might not be availing themselves of bulk-billing GPs, but they still use airports and roads, hospitals and universities. When some one humbugs them in the street they expect that the police will sanction the perpetrator. And what would the entitlement-busters make of the behaviour of the big banks, who have been accused of mistreating and mischarging customers for years? The very same banks who availed themselves of hefty billions of taxpayer financial support during the Global Financial Crisis?

The current generation of seniors benefits far more from government spending, particularly on health. A principled approach to reforming age-based tax breaks would minimise their administration and reduce their budgetary cost, while maintaining the adequacy of retirement incomes and incentives to work. The best balance between these criteria would wind back SAPTO so that it is available only to pensioners, and so that those whose income bars them from receiving a full Age Pension pay some income tax. Seniors should also start paying the Medicare levy at the point where they are liable to pay some income tax. They would then pay a similar amount of tax to younger workers with similar incomes. This package would improve budget balances by about $700 million a year. Seniors also receive a larger rebate on their private health insurance than do younger workers with similar incomes. This larger rebate has no obvious policy rationale. It does not appear to increase private health insurance take-up. Seniors are already adequately protected from higher private insurance costs by “community rating” arrangements. The private health insurance rebate for seniors should be reduced to the same level as for younger workers with similar incomes. This reform would improve budget balances by about $250 million a year, after accounting for the additional government health costs as a small number of seniors choose to discontinue private health insurance.

The current generation of seniors benefits far more from government spending, particularly on health. A principled approach to reforming age-based tax breaks would minimise their administration and reduce their budgetary cost, while maintaining the adequacy of retirement incomes and incentives to work. The best balance between these criteria would wind back SAPTO so that it is available only to pensioners, and so that those whose income bars them from receiving a full Age Pension pay some income tax. Seniors should also start paying the Medicare levy at the point where they are liable to pay some income tax. They would then pay a similar amount of tax to younger workers with similar incomes. This package would improve budget balances by about $700 million a year. Seniors also receive a larger rebate on their private health insurance than do younger workers with similar incomes. This larger rebate has no obvious policy rationale. It does not appear to increase private health insurance take-up. Seniors are already adequately protected from higher private insurance costs by “community rating” arrangements. The private health insurance rebate for seniors should be reduced to the same level as for younger workers with similar incomes. This reform would improve budget balances by about $250 million a year, after accounting for the additional government health costs as a small number of seniors choose to discontinue private health insurance.