The precipitating factor for the Global Financial Crisis [GFC] of 2007–2008 was a high default rate in the home mortgage sector – the bursting of the ‘subprime bubble.’ An unsustainable appreciation in value encouraged large numbers of homeowners to borrow against their homes. The subsequent delinquency rates led to a rapid devaluation of financial instruments such as mortgage-backed securities [MBS], bundled loan portfolios, derivatives and credit default swaps, collectively called ‘derivatives’. As the value of assets plummeted, the buyers for these securities evaporated and banks who were heavily invested in derivatives began to experience a liquidity crisis. Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy. After Lehman’s collapse, no one could understand any particular bank’s risks from derivative trading and so no bank wanted to lend to or trade with any other bank. Because all the big banks’ had been involved to an unknown degree in risky derivative trading, no one could tell whether any particular financial institution might suddenly implode.

The Australian regulators did not see the GFC coming because of fake regulation including euphemistically self-regulation or ‘light touch’ regulation, Government economic policy for the past decades. Treasury economists and the regulators have been taught erroneously at universities that markets are efficient and fully informed; investors are rational; misconduct does not matter, bad loans do not matter; everything is self-adjusted for risk and the markets will find their equilibria in the best of all possible worlds. Regulation is assumed to be unnecessary and only hinders the economy finding its optimal equilibrium. Since the 1981 Campbell inquiry which articulated the policy of ‘minimum regulation and government intervention’, all subsequent reviews and inquiries have sought ways to reduce the intensity of regulation, so as to lower its costs. As the hayne Royal Commission [HRC] has discovered, the regulators have virtually ceased to enforce the law. They found few reasons to monitor the industry proactively for wrongdoings. They do little research or analysis using the enormous data they collect. Their databases are a shambles, with many errors remaining through data disuse. The regulated entities are expected to self-report to the regulators any breaches of the law.

The lax lending boom fuelled the widespread belief that home prices could only go up. Between its peak and trough, the American housing market fell more than 30 per cent, something considered virtually impossible at the time. When home values collapsed, the derivatives built atop of the housing market plunged. These losses, along with the government bailouts, fuelled a crisis of confidence in the health of many of the world’s largest banks. The global financial system ground to a halt and national economies teetered on the edge. Falling prices also resulted in homes worth less than the mortgage loan, called negative equity, forcing the lender to consider foreclosure. The foreclosure epidemic that began in late 2006 drained significant wealth from consumers, losing up to $4.2 trillion in home equity. Defaults and losses on other loan types also increased significantly as the crisis expanded from the housing market to other parts of the economy. Total losses are estimated in the trillions of US dollars globally. The assumption which exonerated the regulators from responsibility, is that OTC derivatives are trades between sophisticated investors, usually between two large global banks, which [are supposed to] know what they are doing and therefore do not need the protection of the regulator. The GFC proved that derivatives were instruments of fraud to hide enormous losses from public view for long periods of time. The fact that the public and the financial system were hurt by derivatives was not properly understood, even by Alan Greenspan, until the 2010 book, The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine by Michael Lewis was written.

In February 2018, Financial Sector Crisis Resolution Act 2018 was passed as further measures to extort the economy to save insolvent Australian banks in a crisis through ‘bail-in’ of bank deposits and other bank liabilities. Such measures, if widely understood by consumers, may increase the likelihood of bank-run instability at the first sign of crisis. Also, since the measures guarantee a rescue effort, they create moral hazard, encouraging the banks to take even more unnecessary risks. The current financial system is morally decrepit, structurally unsound and financially unfair. Bank depositors are being euthanized slowly by low or negative real interest rates. They bear the risk of insolvency losses from bank speculation without getting any of the rewards. Retirement savers have had their superannuation systematically stolen. Everyone, except bank executives, suffers eventually from the asset bubbles created by the financial speculation of the banks, as we are witnessing now in the deflating housing bubble in Australia.

Predicting exactly what will cause the next financial crisis is an impossible task, but it’s undeniable that the same policies that caused the last housing bubble have become even further entrenched. The problem is that this time, the Australian government doesn’t have the mining boom billions to deal with another financial shock.

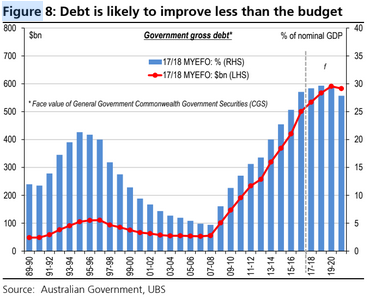

At the beginning of the GFC the Australian government had a debt-to-GDP ratio of around 11%. Today, that level is nudging 30%, nearly three times as much, with little sign of slowing. Further, the Reserve Bank of Australia has little ability to move on the cash rate. Interest rates currently sit around 1.5 per cent, leaving little room for cuts during a time of crisis. With debt levels this high and interest rates already this low, it is reasonable to ask whether our public finances are in good enough shape to survive another global downturn. Household debt to GDP in the US peaked at just under 100% before the GFC. Australia now sits at 122% of GDP, which is the highest in the world among any of the global housing markets deemed at risk [i.e. Sweden, Canada, Hong Kong]. With savings almost depleted entirely, we may enter a period of dis-savings where consumers borrow to fund consumption, which will increase debt levels further. Or they pull back on consumption which will create a negative feedback loop given consumption is roughly 50% of GDP.

The HRC final report contained 76 recommendations which were supposed to improve Australia’s banking, superannuation, insurance and financial advice sectors. It followed 68 days of public hearings, 134 witnesses and 10,000 public submissions, costing $70 million. About 19 of the recommendations suggest potential criminal breaches across 24 financial institutions, including three of the major banks. However, Commissioner Kenneth Hayne’s report does not name any bank executives or individuals in relation to possible criminal charges over misconduct. ASIC and APRA were heavily criticised during the investigation for failing to punish misconduct and impose penalties. What became clear was that APRA had no idea of what was going on in the banking system.

The report cracked down on Australia’s $1.6 trillion mortgage market, recommending that mortgage brokers would need to act in the best interests of borrowers and if this was breached, brokers could face a civil penalty. To address conflicts of interest, Hayne recommended that the borrower, not the lender, should pay the mortgage broker. Firstly, the report recommended a ban on lenders paying trail commissions to brokers – that is, where an annual fee is paid over the life of a product – and secondly, a ban on lenders from paying commissions to brokers altogether. In response, the government has indicated it will ban lender-paid commissions from 1 July, 2020.

One of the biggest scandals uncovered by the banking royal commission was the charging of fees for no service to clients. To further tackle conflicts of interest, the report proposed that financial advisers be legally required to disclose any potential conflict to clients and clearly explain why they’re not independent, impartial and unbiased. In terms of life insurance products, the report recommended commissions be ultimately reduced to zero. Hayne also proposed that each financial adviser be individually registered and that a new disciplinary body be established.

Addressing Australia’s $2.6 trillion super industry, the report recommended banning funds from charging advice fees. The HRC agreed with the Productivity Commission that default super accounts should only be created for new workers or those who don’t have an existing super account and noted that around 40% of Australians held more than one account as at June 2017. To combat this, each person should only have one default super account and a mechanism should be developed to ‘staple’ a person to a single default account. The report also shone the spotlight on super trustees and recommended that they be banned from doing anything that may influence an employer to nominate the trustee’s super fund as the default fund for their employees. In addition, it recommended the Banking Executive Accountability Regime [BEAR], a scheme which makes senior bank executives responsible for specific activities carried out by their institution, be extended to super trustees.

Nearly six months later, with the exception of a couple of scapegoats on extended leave, no one is being held responsible. This may be due to APRA being held in check during the election campaign but it is more likely that the Government [even if it changes in May] doesn’t understand the magnitude of the problem, cannot conceive of the ramifications of a system failure and, worse, seems to have no solutions at hand. Cosmetic changes to the rules for mortgage brokers and financial planners and [even more] tinkering with default super funds do not address the systemic failures of the banking system. It all boils down to an understanding of money.

On 4 May 1970, a notice appeared in the Irish Independent newspaper in the Republic of Ireland, titled ‘Closure of Banks’. It read:

As a result of industrial action by the Irish Bank Officials’ Association … it is with regret that these banks must announce the closure of all their offices in the Republic of Ireland from 1 May, until further notice.

Banks in Ireland did not open again until 18 November, six-and-a-half months later. To everyone’s surprise, instead of collapsing, the Irish economy continued to grow much as before. A two-word answer has been given to explain how this was possible: Irish pubs. Andrew Graham, an economist, visited Ireland during the bank strike and was fascinated by what he saw:

Because everyone in the village used the pub, and the pub owner knew them, they agreed to accept deferred payments in the form of cheques that would not be cleared by a bank in the near future. Soon they swapped one person’s deferred payment with another thus becoming the financial intermediary. But there were some bad calls and some pubs took a hit as a result. My second experience is that I made a payment with a cheque drawn on an English bank (£1 equalled 1 Irish punt at the time) and, out of curiosity, on my return to England, I rang the bank (in those days you could speak to someone you knew in a bank) and they told me my cheque had duly been paid in but that on the back were several signatures. In other words, it had been passed on from one person to another exactly as if it were money.

The Irish bank closures are a vivid illustration of the definition of money: it is anything accepted in payment. At that time, notes and coins made up about one-third of the money in the Irish economy, with the remaining two-thirds in bank deposits. The majority of transactions used cheques, but paying by cheque requires banks to ensure that people have the funds to back up their paper payments. In a functioning banking system the cheque is exchanged at the end of the day, and the bank credits the current account of the goods and services supplier. If the writer of the cheque does not have enough money to cover the amount, the bank bounces the cheque, and the shop owner knows immediately that he has to collect in some other way. That’s why cheque funds were not ‘cleared’ for a couple of days.

Today, a debit card works by instantly verifying the balance of your bank account and debiting from it. If you get a loan to buy a car, the bank creates the money and credits your current account; you then initiate a bank transfer to the car dealer to buy the car. This is money in a modern economy. So what happens when the banks close their doors and everyone knows that electronic exchanges will not happen, you would not trust someone offering a cheque in exchange for goods or services. You would insist on being paid in cash. But there is not enough cash in circulation to finance all of the transactions that people need to make. Everyone would have to cut back, and the economy would suffer.

How did Ireland avoid this fate? Cheques [commonly called instruments or promissory notes] were accepted in payment as money, because of the trust generated by the pub owners. Publicans were prepared to accept cheques, which could not be cleared in the banking system, as payment from those judged to be trustworthy. During the six-month period that the banks were closed, about £5 billion of cheques were written by individuals and businesses, but not processed by banks. It helped that Ireland had one pub for every 190 adults at the time. With the assistance of pub and shop owners who knew their customers, cheques could circulate as money. With money in bank accounts inaccessible, the citizens of Ireland created the new money needed to keep the economy growing during the bank closure.

The major problem with the Australian banking system is that very few, either participants or policy -makers understand how it works. Ken Henry, because of his position in Treasury and later the Chairman of nab, probably does and has seen the writing on the wall, resulting in his departure.

It is not widely understood that banks create the money supply by ‘lending’ to borrowers for two main purposes, consumption [to buy goods and services] and/or investment. When the investment loan is put to productive use it adds to the GDP but when used for speculation, as in the purchase of existing real estate [e.g. negatively geared investment property], sharemarket assets and high risk derivatives, it simply drives up asset prices, usually creating a ‘bubble’.

The Banking Royal Commission simply skirted around the systemic failures of the whole process and consequently the banks continue to act as though nothing is changed.

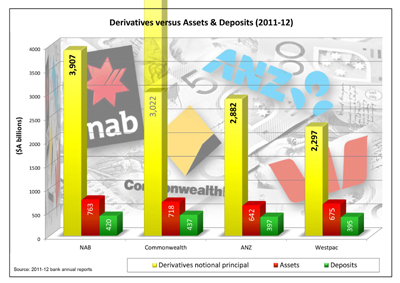

And the wholesale collapse of the system is inevitable because banks will continue to service their large customers [at the expense of the SMEs], often using derivatives, because it is much more profitable to do so. APRA continues to stumble around in the dark because two of the major players have refused to publish their exposure to derivatives since 2012.

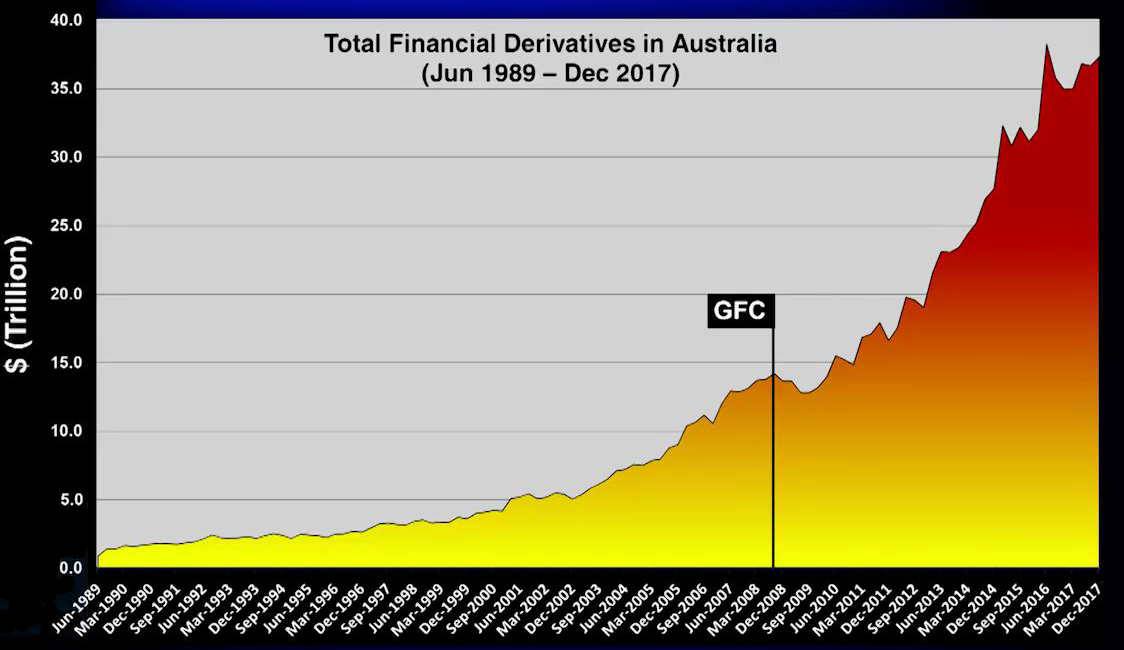

Banks who play in the derivatives area may have additional risks in their business, which are not knowable, but potentially large. In a crisis, it risks the rest of the business. There is no ring fence separating ordinary depositors from this high risk speculation. The bottom line is the $37 trillion is a good approximation of the current gross exposures in our banking system, and this dwarfs the banks’ current balance sheets, and the countries total economy. The risks are enormous, and in a system-wide banking crash, when multiple parties are exposed, a bail-out might be enough to swamp the entire economy. That’s how big the potential risks are. In a February 2018 report the AFR wrote;

“International investors are being urged to steer clear of banks in Australia, Canada and Sweden by a leading investment consultancy, which has sounded the warning about the risk they may pose to the entire financial system if interest rates rise and the Chinese economy slows. The combined weight of these banks on world equity markets is four times larger than their share of the global economy, London-based Absolute Strategy Research (ASR) said in a note to clients. Investors were underestimating just how damaging a group of countries that account for just 3 per cent of global GDP can be. The key lesson for us from [the global financial crisis] was that systemic risk is multiplicative, rather than additive. It was the collapse of relatively small, but important, institutions that triggered the market meltdown”.

Alan Kohler wrote way back in 2014;

Although central banks and bank regulators are working hard to control banks’ balance sheet leverage before the next crisis hits, the continuing growth in derivatives trading by banks is undermining those efforts. And as Glenn Stevens [the RBA Governor] points out, when there’s macroeconomic stability and growth, as there is now, leverage tends to increase:

The big question is not, in fact, what more demanding capital standards will do to economic growth. The question is: what will economic growth, or lack of it, do to banks’ capital positions?

And although Glenn Stevens didn’t say this, it seems that the leverage problem these days is not excessive lending on housing, as it was in 2005-06, but exposure to derivatives. By far the largest type of derivatives trading involves interest rate swaps, in which two parties agree to exchange interest cash flows, usually with one of them paying a fixed rate and getting a floating rate in return. It’s simply a way of betting on interest rate movements instead of horses, or flies on the wall, and always involves significant leverage.

Source: Digital Financial Analytics.

The shocking truth is that there has been no effective regulation of derivatives put into place since they brought about the GFC. Even more shocking is that the size of the derivatives market has exploded since that time. The total notional value, or face value, of the global derivatives market when the housing bubble popped in 2007 stood at around $500 trillion. New numbers from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), which tracks the sales of derivatives, shows the Over-The-Counter derivatives market alone has grown to a notional value of at least $700 trillion. You might not completely understand the totally astronomic scale that number represents. To put it into perspective, the gross domestic product of the entire world stands at around just 60 trillion dollars. The US residential real estate market is worth 23 trillion dollars. The value of the entire world’s stock markets is about 50 trillion dollars. Derivatives currently represent around ninety percent of the world’s financial liquidity. In addition to remaining vastly unregulated and opaque, the market for the creation and exchange of derivative contracts operates much like the roulette wheel at a casino.

Derivatives have become instruments that enable banks to gamble with vast amounts of money in order to produce high returns on their investments. A derivative is essentially a bet. They were used responsibly in business for centuries as insurance against loss. For example, in a simple derivative contract a farmer might bet against the success of his own crop to insure that if his crop fails he will not be at a total loss. If the crop is productive that year, he loses the bet but reaps a profit from sale of his product. If the crop fails, on the other hand, he can collect on the bet and make up for his loss of profit. Derivatives provide a way to produce even returns in markets that are subject to uneven productivity.

One of the problems with today’s derivatives market is that it has expanded from its initial purpose of hedging and simple speculation to allow for betting on just about anything financial. During the housing bubble we saw banks like Goldman Sachs betting on the failure of the very products they were selling as “AAA” rated safe investments. Today’s synthetic derivatives market even allows for betting on other people’s bets. This has created a multi level ponzi scheme of derivatives that are based on the success of other derivatives, using huge degrees of leverage at every layer. Today, when a farmer bets against his crop, banks and hedge funds pounce on the opportunity to bet on the success of that farmer’s derivative contract, and then other bets are placed on the success of those bets and so on. With each bet using leverage to inflate the face value of the contract, we end up with multiple bets that have a combined value exceeding the actual value of the farmer’s crop many times over.

Another problem with today’s derivatives market is that the contracts are so loosely controlled that no one is really sure of the actual numbers concerning its size or structure. Governments have colluded with Wall Street and the banking industry to ensure there is no central clearing house for derivative transactions, no central reporting and no disclosure. Banks don’t tell investors how much of the “notional amount” that they could lose in a worst-case scenario, nor are they required to. Even a savvy investor who reads the footnotes can only guess at what a bank’s potential risk exposure from the complicated interactions of derivatives might be. And when experts can’t assess risk, and large bets go wrong simultaneously, the whole financial system can freeze and lead to a global financial meltdown. Meanwhile, there is no other game in town to realize the kind of profits banks and their clients demand these days, so the roulette table is the place to be. The big 4 merely left the housing market behind and started betting more furiously on other things, like the failure of the Greek economy, the hedge funds of maverick financial traders and who knows what else.

Another problem with today’s derivatives market is that the contracts are so loosely controlled that no one is really sure of the actual numbers concerning its size or structure. Governments have colluded with Wall Street and the banking industry to ensure there is no central clearing house for derivative transactions, no central reporting and no disclosure. Banks don’t tell investors how much of the “notional amount” that they could lose in a worst-case scenario, nor are they required to. Even a savvy investor who reads the footnotes can only guess at what a bank’s potential risk exposure from the complicated interactions of derivatives might be. And when experts can’t assess risk, and large bets go wrong simultaneously, the whole financial system can freeze and lead to a global financial meltdown. Meanwhile, there is no other game in town to realize the kind of profits banks and their clients demand these days, so the roulette table is the place to be. The big 4 merely left the housing market behind and started betting more furiously on other things, like the failure of the Greek economy, the hedge funds of maverick financial traders and who knows what else.

The solution is relatively simple, revert to a time when regional banks were the financial intermediaries for the community they served, the ‘irish pubs’ and derivatives trading restricted to investment banks completely separated from ordinary deposits.

The DFA submission to the Senate inquiry included:

The recently complete Royal Commission found regulation and changes to the law alone cannot address the issues exposed during the hearings. The culture within the finance sector needs to be changed, to put customers at the centre of their business. Whilst talk is cheap however, there is little evidence of substantial change as yet. In addition, the current capital adequacy rules favour mortgage lending relative to productive lending to business and as a result according to SME surveys, many businesses are unable to obtain finance [or can only do so by securing their property]. We believe the various risk weights reflect a myopic view of the financial system and they need to be changed. Too much of the bank’s portfolio of loans – up to 65% – is against residential property – this is extraordinarily high by international standards, and presents a significant risk, to say nothing of the lack of business investment which has resulted.

However, we hold the view that the major financial sector players are too complex to be managed effectively, scale is now a disadvantage. Thus, we believe there is a case to break up the banks into smaller units. This would involve both vertical disaggregation [separation of advice, sales and product manufacture] and horizontal disaggregation [separate of wealth, insurance, retail banking and investment banking]. In addition, there are significant risks from their operations in derivatives, and in an integrated environment, costs, risks and profits are cross linked. Given the size of the

derivatives sector [significantly larger than before the GFC], the systemic risks are significant. To counter this, we advocate the implementation of a modern Glass Steagall separation, where the high-risk speculative activities are separated from the normal lending, payment and deposit functions within banking. This would have the added benefit of reducing the potential risks of a bank deposit bail-in in a time of crisis. Evidence suggests that the existence of a modern separation would reduce risk and limit systemic risk. In a post Glass Steagall world, bank lending would be more aligned with the deposits available, so their ability to make loans “from thin air” as in the current system would be curtailed. They would also be more inclined to make loans for truly productive purposes.The Council of Financial Regulators is the peak body, chaired by the RBA, where key policy is set, with the Treasury, ASIC, APRA and others. However, other than scant minutes (a recent innovation) none of their deliberations are made public, and it appears that all entities have been sharing the same view that growing housing credit was the chosen growth lever of choice following the mining boom. It appears that the weak supervisory approach from ASIC and APRA stemmed from this policy and was supported by policy rates being set too low. As a result, the systemic risks have been underestimated, and the economic platform for the country narrowed. The Royal Commission highlighted the lack of coherence, and alignment. We also would argue that APRA has myopically focussed on financial stability, at the cost of good consumer outcomes and competition, that the regulations favour large players over small players, that the RBA policy rates are too low, and the ASIC so far is still perceived as a weak and ineffective regulator.

If implemented, the outcomes of the Banking System Reform (Separation of Banks) Bill 2019 would be to:

• Protect deposits, and ensure deposits are only used for normal lending, not speculative activities.

• Keep more money in the real economy and available for banks to lend to productive

enterprises, especially lending to commercial entities, many of whom today are unable to access finance.

• Separate the sales, advice and manufacturer functions to remove the current conflict of interest, conflicted remuneration, and poor customer outcomes and cross selling between banking, insurance and wealth management.

• Stop banks from securitising mortgages, which is the repackaging and on-selling of mortgage pools to other banks into risky derivatives. This would put a brake on mortgage fraud and excessive mortgage lending to risky borrowers.The current regulators, major existing players, and even Treasury will resist reform, but the case for the Banking System Reform (Separation of Banks) Bill 2019 is compelling. In summary, bad behaviour would be easier to identify and manage, productive lending would be encouraged, customer pricing would be more transparent, and systemic risks would be better managed, alleviating the need for bank bail-in during difficult times.

Summary Submission Supporting the Banking System Reform (Separation of Banks) Bill 2019 by Wilson Sy – 7 April 2019

The Hayne royal commission (HRC) exposed a systemic failure of financial regulation, but it was not allowed to investigate the reasons. This submission explains that the integrated financial system is too complex to regulate and that fake regulation does more harm than good. The answer to better regulation is to simplify and improve the financial system through structural separation.

The HRC was forbidden by its terms of reference to investigate or recommend structural changes to the financial system, such as breaking up the major banks in the manner of the proposed Bill. Hence the absence of a HRC recommendation to separate the banks is not a valid argument against banking separation proposed by the Bill. Also, the Australian Treasury has confused the fact that our regulators are currently unable to come to grips with the fact that our financial system needs to be structurally separated. Our financial system is too highly concentrated with highly integrated major banks.

The privatisation of the Commonwealth Bank was a financial disaster for the Australian public, although investors in the float did very well indeed. Prior to the sale of the first tranche of shares in 1991 involved the issue of 835 million shares at par value $2, the with an issue price which was set at $5.40. This implies a valuation of $4.5 billion for the Bank as a whole. The second tranche of shares in 1993 ensured that the government received an amount close to the market price of the shares at the date of sale, which turned out to be around $9.50, implying a valuation for the Bank as a whole of $8 billion. The final share offer for the Bank was announced in June 1996. The total proceeds from the three stages of the sale amounted to about $7.8 billion in 1995-96 dollars.

Average real annual profits over the period 1988-93 were around $560 million. Computing the present value of this stream of profits at a discount rate of 5 per cent yields a value of $11.2 billion for the Bank as a whole. Therefore, even if profits had not increased after 1993, the public would have incurred a loss of around $3.5 billion from the privatisation. In fact, primarily because of the removal of restrictions on the monopoly power of the banks, profits have soared. Profits for the three years from 1998 to 2000 totalled $5.4 billion, or more than half the total sale proceeds received by the Australian public. Shareholders who bought into Australia’s first big privatisation, the 1991 float of the Commonwealth Bank, are sitting on hefty gains in their investment, as the bank marks a quarter of a century as a listed company. If an investor had bought the minimum 400 shares in the bank in the 1991 float, for $2,160, that investment would now be worth $131,171 if they had reinvested the dividends. Taking into account the effect of franking credits, the shares would be worth nearly $148,000. Financial deregulation has been similarly disastrous. Since the advent of financial deregulation, banks have raised fees and charges, cut services and exploited their collective monopoly power whenever possible.

The new Government could go further and instruct APRA to bring immediate legal proceedings against all of the criminals exposed in the HRC and, pending the outcomes, further protect customers by revoking some banking licences. It should ‘re-nationalise’ CBA by replacing small shareholdings and superannuation fund holdings with bonds at face value and instruct the Future Fund to purchase the remaining shares at a significant discount to face value. The investment part of the bank should then be sold off and local CBA branches report to regional offices that had representation from local communities included in their decision making capabilities. In this way the infrastructure of the bank could be utilised by the regional offices to provide an efficient, community focussed source of investment funds. Only when the banking system is based on small, member owned or community run organisations will some commonsense be returned to the banking system.