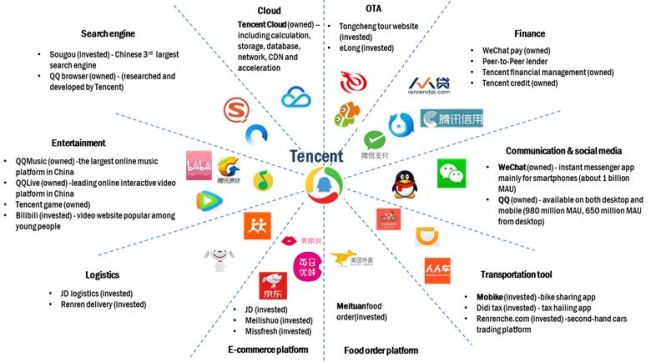

Pony Ma is the founder, president, chief executive officer, and executive board member of Tencent Holdings, Ltd., one of the most important telecommunications companies in China. Tencent, with its well-known penguin icon, controls China’s largest instant messaging (IM) service and has expanded to other mobile telephone and internet services. Ma’s interest in Tencent has made him quite wealthy, and he is regarded as one of China’s most desirable bachelors. Born around 1971, on the island of Hainan, China, Ma uses the nickname “Pony” which is derived from the English translation of his family name, which is “horse.”

Pony Ma is the founder, president, chief executive officer, and executive board member of Tencent Holdings, Ltd., one of the most important telecommunications companies in China. Tencent, with its well-known penguin icon, controls China’s largest instant messaging (IM) service and has expanded to other mobile telephone and internet services. Ma’s interest in Tencent has made him quite wealthy, and he is regarded as one of China’s most desirable bachelors. Born around 1971, on the island of Hainan, China, Ma uses the nickname “Pony” which is derived from the English translation of his family name, which is “horse.”

When he was a teenager, he moved to Shenzhen. In 1993, he graduated from Shenzhen University, earning his B.S. in software engineering. After graduation, Ma became employed by China Motion Telecom Development, Ltd. He worked in the Internet paging system development, in charge of research and development. This company supplied such systems to the Chinese government. He also worked for Shenzhen Runxun Communications Co., Ltd., where he also worked in the research and development area. He oversaw Internet calling systems.

Ma soon came to the conclusion that China was ready for its own IM service. To that  end, he and four friends founded Tencent in 1998. They began the company with only $120, 000, primarily garnered from money earned while playing the stock market. The first years of the company were difficult. Ma had to wear many hats in the first year, from janitor to website designer, as the company lacked experienced employees and financial health.

end, he and four friends founded Tencent in 1998. They began the company with only $120, 000, primarily garnered from money earned while playing the stock market. The first years of the company were difficult. Ma had to wear many hats in the first year, from janitor to website designer, as the company lacked experienced employees and financial health.

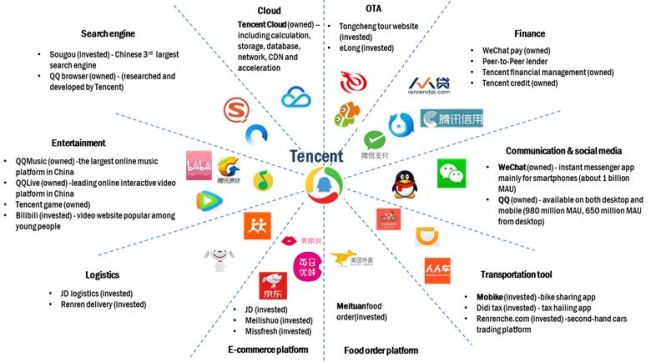

The company’s early offerings included e-mail and internet paging services. Within a few years, Tencent added more employees and Ma began focusing on strategic planning, positioning, and management of the company. He was eventually named chief executive officer, executive board member, and chairman of the board. By 1999, Tencent launched the product that would bring it much success and wealth. After initially focusing on a text messaging product, it offered its instant messaging service, originally called OICQ, but later known as QQ. Initially, OICQ was only one of many IM services in China and did not have a big market share.

Ma changed the fortune of his company when OICQ began being offered as a free download. The free download attracted many young users. Demand grew high, with as many as five million users added in one year. This success created problems for Ma and his young company. Because Tencent could not afford the servers or server space needed to service all these customers, Ma tried to sell OICQ, but no deal could be reached. American venture capitalists eventually invested a couple million American dollars to keep Tencent afloat. At that time, OICQ became QQ.

To continue Ma’s company’s success, QQ users were offered more value-added services each year, such as QQ membership, ring tones, and other services for cellular telephones, as well as the ability to customize some products. Ma also signed deals to work with a number of internet technology companies around the world. By 2004, Tencent was the largest IM service in China. About 335 million Chinese, or 74 percent of the market, used Tencent’s services. Ma himself was worth $190 million in 2004. He was named a Global Business Influential by Time magazine as well as one of the top ten Economic Influentials in Innovation by Beijing, China’s China Central Television.

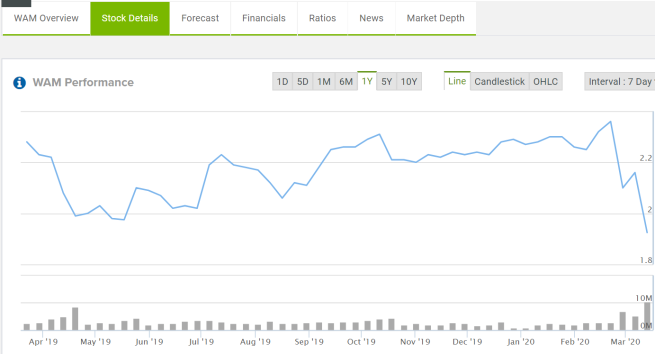

In June of 2004, Tencent had its initial public offering (IPO) in the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. It was successful and within a few months, the stock prices had risen nearly 60 percent. Profits rose more than 40 percent from the beginning of 2004. Ma said the company went public in part to have the funds to purchase companies to help enhance the QQ IM service. Ma did not let Tencent rest on its laurels, but continued to expand around its core IM business. He hoped to buy firms working in new areas like wireless technologies to help Tencent retain its position as the number-one company in China. Such acquisitions were intended to keep Tencent competitive in the face of ever increasing foreign competition. Microsoft and Yahoo! both were competing for the same market in China. While Tencent was doing well, it was already facing eroding profit margins as the cost of development and marketing continued to rise.

In 2004, Ma announced that different kinds of games, created within Tencent, would be added regularly to Tencent’s services, to keep the customers’ interest. This strategy paid off by attracting more than one million online gamers in China, making it the largest such service in that country. Ten-cent also began offering the first licensed radio broadcasts over the Internet in China. However, IM remained the most significant Tencent service. By early 2005, Tencent was the most popular IM service in Asia with 150-160 million active users. Because other companies offered free IM, like Microsoft, Ma looked for new ways to make that service profitable. One way was with the development of new paying services such as an IM product solely for businesses in China called RTX (Real Time Xchange System), launched in 2005. RTX was soon used by 85, 000 companies in China. Tencent also added profits by licensing the QQ brand name to another Chinese company, Guangzhou Donglihang, to produce products like toys with the QQ name.

Ma’s next move was to add e-commerce, primarily consumer to consumer sites like auction sites for the registered members of its IM service as well as through its website. His goal was to make Tencent’s services the focus of its users’ Internet life, as many of its subscribers were under 30 years of age. Mary Meeker, an analyst at Morgan Stanley, believed Ten-cent was quite successful in this arena. She told Bruce Einhorn of BusinessWeek Online , “If you look at instant messaging and the ability to enhance services and generate revenue from them, Tencent is probably the leader in the world.” Ma continued on this path by signing a partnership deal with Google. Despite the deal, Ma did not intend to sell out to a foreign company, but continued to add more gaming, community searches, and advertising to retain its customers and add new ones. By August of 2005, Tencent had more than 438 million registered users and 173 million active users. Revenues continued to grow. Ma wanted to further expand Tencent and keep its position as the leading IM service in China. Making partnership deals with other companies, like Google, were ideal. Ma told Liu Ke of China Today , ” Concentration does not mean stubbornly sticking to your own ideas. When we see an opportunity, we grasp it. To succeed in this game, you need an acute sense of business and the markets. We view our challenges not as more pressure, but as roads to success.” Read more:

Ma, 42, is benefiting from Tencent’s development of mobile Internet games and services, especially WeChat, an instant messaging and social networking app known as Weixin in China. More than 84% of China’s Internet users regularly access instant messaging, making it the most popular online application, surpassing search engines, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. China’s most powerful Internet company is headquartered in a bland, glassy tower in southern Shenzhen. Unlike Silicon Valley’s funky campuses, there is nothing to reveal that this might be a hub of creativity. An insurance company, perhaps? In the middle of its nondescript, corporate lobby, an information desk stands next to the only sign of personality: a pair of giant plush penguins, the Tencent mascot times two. Nearby, an iPad displays stats on the company’s messaging services. But when I pull out a notebook and start jotting down the numbers, the receptionist waves her hand. “Oh no, that’s not updated!” she says. “It’s just for show.”

A ‘tour’ of the company starts with a museum-like exhibit of Tencent products. The experience feels like a throwback to the tightly controlled Communist Party –sponsored trips reporters went on back in the 1980’s, before the country really started opening up to the outside world. An attractive, young, fluent English speaker shuffles a visitor from one screen to another. The three other public relations officers offer no analysis of the firm, saying they will get back to the visitor on any questions they have. What about the management style of the somewhat mysterious CEO, Pony Ma, and there is an awkward pause. Then the guide brightly tells me: “It’s very equal here. We all call him Pony!” And that’s the tour.

This is all still fairly common in China, a country where public relations is often equivalent to stonewalling. But China’s Internet industry doesn’t need feel-good stories in order to be noticed: It is becoming increasingly competitive with the rest of the world–and Tencent, which was recently valued at more than $139 billion on the Hong Kong stock exchange, is about to become its breakout star. “Chinese companies are much more innovative [than U.S. companies] in integrating social media, gaming, and e-commerce to make an amazing user experience,” says Sun Baohong, associate dean of global programs at Beijing-based Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business.

Chinese Internet companies have some inherent advantages: Facebook is banned in the country, and Google retreated from it. But Tencent’s success can’t be pinned on that handicap. The company embraced mobile years before Facebook, and has built a platform, used by 355 million active users, that functionally offers every popular service that Americans are familiar with–including Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, and Zynga, all wrapped up in one app. It keeps adding new functions at a fast clip, such as a new Uber-like taxi finder that was used 21 million times in the first few weeks. And now it’s expanding beyond China. Tencent has already started exploring international markets beyond China’s borders, with notable success in Southeast Asia and India. It has funded a number of small American startups and acquired or taken stakes in big gaming companies, while recasting its popular app for an international audience. “Will Tencent join the likes of Amazon, Google, Facebook, and Twitter?” says Aditya Rathnam, cofounder of Kamcord, a San Francisco startup that Tencent invested in. “They already are in that league. The rest of the world just doesn’t know it yet.” But to truly make it in the West, Tencent will have to overcome a hurdle no other global tech giant faces: It has to act, at least in public, as two essentially separate companies. Inside China, Tencent is everything it must be: historically aggressive, unhesitant to copy others’ work, and very close to the government and its attendant propagandists. But outside China, Tencent will have to simultaneously engage with a world that doesn’t take kindly to any of that. For now, its coping strategy may explain why Ma and Tencent’s other top executives generally refuse to talk to the press: their answers to difficult political questions could either enrage Beijing or turn off foreign readers.

What most draws people’s attention is the company’s charitable activities. In 2005, Tencent called on netizens to make long-term donations to poor schools and poverty-stricken people in mountainous areas. In 2007, the company established the first Internet charity, investing over 50 million yuan ($7.35 million). Tencent netizens donated 23 million yuan ($3.38 million) to Sichuan Province after an 8.0-magnitude earthquake hit there in May 2008. With the development of instant communication programs, however, more competitors have emerged. NetEase’s POPO, Microsoft’s MSN and NET Messenger, Yahoo Messenger and AOL Instant Messenger pose a big challenge to Tencent. But Ma is not worried. In his view, the instant communication market is not as simple as selling a soft product. It needs to satisfy users with products, services and operations, which Tencent is good at. “We welcome competition strategically, but tactically we attach great importance to it. We analyze the potential demands of our users, so as to develop more products to cater to them,” Ma was quoted as saying by Economic Reference News. According to Ma, in 2009 Tencent Inc. will also continue to improve its Internet gaming by developing and launching at least one mini online game every month, one medium-sized game every three months, and a multiplayer game every nine months.

THE most recognisable face of Chinese capitalism belongs to Jack Ma, the founder of  Alibaba, an e-commerce juggernaut matched in size only by Amazon. Mr Ma, who launched Alibaba from a small apartment in Hangzhou in 1999, is an emblem of China’s extraordinary economic transformation.

Alibaba, an e-commerce juggernaut matched in size only by Amazon. Mr Ma, who launched Alibaba from a small apartment in Hangzhou in 1999, is an emblem of China’s extraordinary economic transformation.

His announcement that he will step down as the firm’s chairman to concentrate on philanthropy, was greeted with comparative calm by investors. He actually stopped being chief executive in 2013; Alibaba’s share price has more than doubled since its initial public offering, the world’s largest-ever, in 2014. But one question presents itself: could China produce another story to match his? The answer is almost certainly not. There are some very good reasons for that. China’s own rise is an unrepeatable one.

Jack Ma was born Ma Yun on 10 September 1964 in Hangzhou, China. When he was twelve, he bought a pocket radio and started to listen to English radio everyday. He began studying English at a young age by conversing with English-speakers at Hangzhou International Hotel. For nine years, Ma would ride 17 miles on his bicycle to give tourists tours of the area to practice his English. He became pen pals with one of those foreigners, who nicknamed him “Jack” because he found it hard to pronounce his Chinese name. Later in his youth, Ma struggled attending college. The Chinese entrance exams are held only once a year and, because he was bad at Maths, took four years to pass. While at school, Ma was head of the student council. After graduation, he became a lecturer in English and international trade at Hangzhou Dianzi University. He also applied ten times to Harvard Business School and got rejected each time.

Ma applied for 30 different jobs and got rejected by all. “I went for a job with the police; they said, ‘you’re no good'”, Ma told interviewer Charlie Rose. “I even went to KFC when it came to my city. Twenty-four people went for the job. Twenty-three were accepted. I was the only guy …”. In 1994, Ma heard about the Internet and also started his first company, Hangzhou Haibo Translation Agency. In early 1995, he went to the US with his friends, who helped introduce him to the Internet. Although he found information related to beer from many countries, he was surprised to find none from China. He also tried to search for general information about China and again was surprised to find none. So he and his friend created an “ugly” website related to China. He launched the website at 9:40 AM, and by 12:30 PM he had received emails from some Chinese investors wishing to know about him. This was when Ma realized that the Internet had something great to offer. In April 1995, Ma and He Yibing [a computer teacher] opened the first office for China Pages and Ma started their second company. On May 10, 1995, they registered the domain chinapages.com in the United States. Within three years, the company had made 5,000,000 Chinese Yuan which at the time was equivalent to US$800,000.

Ma began building websites for Chinese companies with the help of friends in the US. He said that “The day we got connected to the Web, I invited friends and TV people over to my house”, and on a very slow dial-up connection, “we waited three and a half hours and got half a page”, he recalled. “We drank, watched TV and played cards, waiting. But I was so proud. I proved the Internet existed”. At a conference in 2010, Ma revealed that he has never actually written a line of code nor made one sale to a customer. He acquired a computer for the first time at the age of 33. From 1998 to 1999, Ma headed an information technology company established by the China International Electronic Commerce Center, a department of the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation. In 1999, he quit and returned to Hangzhou with his team to found Alibaba, a China-based business-to-business marketplace site in his apartment with a group of 18 friends. He started a new round of venture development with 500,000 yuan. When Mr Ma, then an English-language teacher, launched Alibaba, the country was still gearing up to join the World Trade Organisation. Its GDP per head, in terms of purchasing-power parity, stood at under $3,000; it is now more than six times higher. The internet was still young, too. Less than 1% of Chinese had access to the web back then, compared with some 36% of Americans. As incomes grew and connections proliferated, Mr Ma took full advantage.

In October 1999 and January 2000, Alibaba twice won a total of a $25 million foreign venture capital investment. The program was expected to improve the domestic e-commerce market and perfect an e-commerce platform for Chinese enterprises, especially SMEs, to address World Trade Organization (WTO) challenges. Ma wanted to improve the global e-commerce system and from 2003 he founded Taobao Marketplace, Alipay, Ali Mama and Lynx. After the rapid rise of Taobao, eBay offered to purchase the company. However, Ma rejected their offer, instead gathering support from Yahoo co-founder Jerry Yang with a $1 billion investment. In September 2014 it was reported Alibaba was raising over $25 billion in an IPO on the New York Stock Exchange. Alibaba became one of the most valuable technology companies in the world after raising the full $25 billion, the largest initial public offering in US financial history. Ma served as executive chairman of Alibaba Group, which is a holding company with nine major subsidiaries: Alibaba.com, Taobao Marketplace, Tmall, eTao, Alibaba Cloud Computing, Juhuasuan, 1688.com, AliExpress.com, and Alipay. In November 2012, Alibaba’s online transaction volume exceeded one trillion yuan.

On 9 January 2017, Ma met with United States President-elect Donald Trump at Trump Tower, to discuss the potential of 1 million job openings in the following five years through Alibaba’s interest in the country. On 8 September 2017, to celebrate Alibaba’s 18th year of establishment, Ma appeared on stage and gave a Michael-Jackson-inspired performance. He performed part of “Can You Feel The Love Tonight” at the 2009 Alibaba birthday event while dressed as a heavy metal lead singer. In the same month, Ma also partnered with Sir Li Ka-shing in a joint venture to offer a digital wallet service in Hong Kong. Ma announced on 10 September 2018 that he would step down as executive chairman of Alibaba Group Holding in the coming year. Ma denied reports that he was forced to step aside by the Chinese government and stated that he wants to focus on philanthropy through his foundation. Daniel Zhang would then lead the way ahead for Alibaba as the current executive chairman.

On 9 January 2017, Ma met with United States President-elect Donald Trump at Trump Tower, to discuss the potential of 1 million job openings in the following five years through Alibaba’s interest in the country. On 8 September 2017, to celebrate Alibaba’s 18th year of establishment, Ma appeared on stage and gave a Michael-Jackson-inspired performance. He performed part of “Can You Feel The Love Tonight” at the 2009 Alibaba birthday event while dressed as a heavy metal lead singer. In the same month, Ma also partnered with Sir Li Ka-shing in a joint venture to offer a digital wallet service in Hong Kong. Ma announced on 10 September 2018 that he would step down as executive chairman of Alibaba Group Holding in the coming year. Ma denied reports that he was forced to step aside by the Chinese government and stated that he wants to focus on philanthropy through his foundation. Daniel Zhang would then lead the way ahead for Alibaba as the current executive chairman.

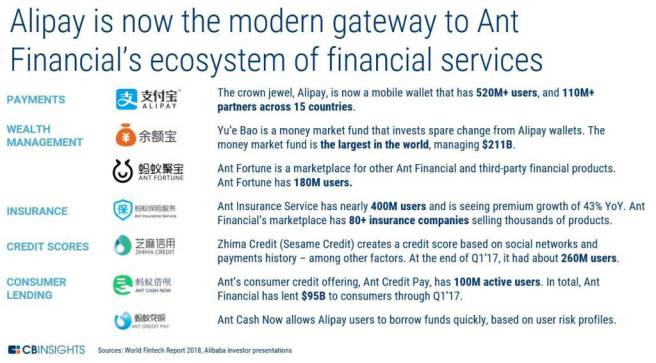

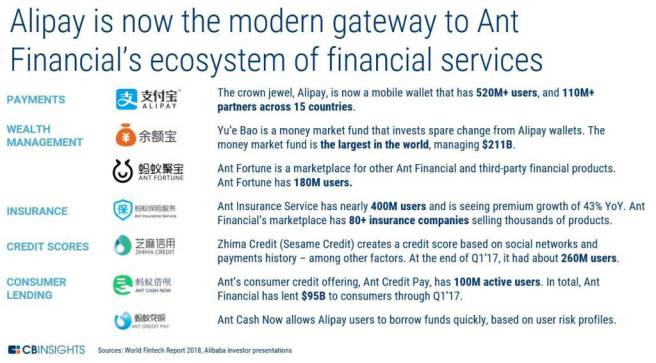

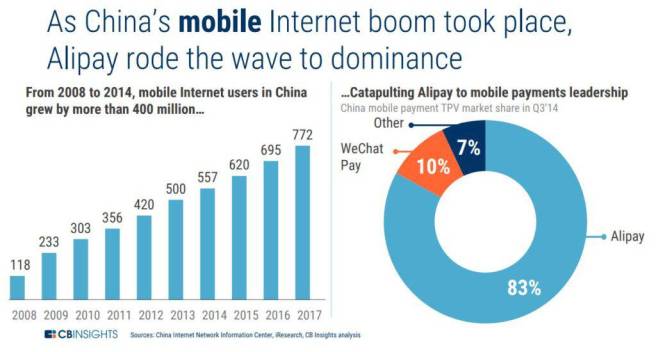

Ant Financial Services Group, officially established in October 2014, is an innovative technology provider that aims to bring inclusive financial services to the world. Headquartered in Hangzhou, China, the operator of Alipay, an online payment service launched in 2004 which has since evolved into the world’s largest payment and lifestyle platform. As a member of the Alibaba digital economy, Ant Financial is working hand in hand with Alibaba Group to make it easy to do business anywhere across the world. Through our innovative technologies, Ant Financial is committed to helping global consumers and small-and-micro enterprises gain access to inclusive financial services that are secure, green, and sustainable, creating greater value for society and bringing equal opportunities to the world. We do not pursue size or power; we aspire to be a good company that will last for 102 years. We will work with Alibaba Group to push forward the goals of the Alibaba digital economy for 2036: to serve 2 billion global consumers, empower 10 million profitable businesses and create 100 million jobs.

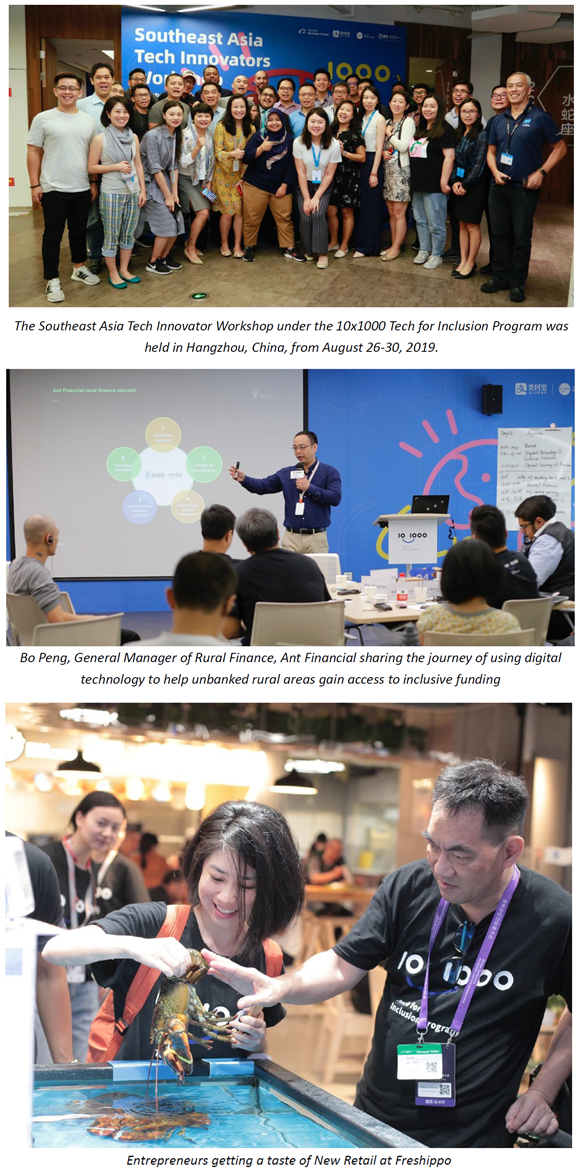

September 5, 2019 – A group of CEOs from a range of Southeast Asian based firms have had the unique opportunity to take home the secret sauce of leveraging digital technology to help support their own firms as well as the wider economy. The cohort came together to attend a Tech Innovator Workshop in Hangzhou, China, under the 10×1000 Tech for Inclusion program. The five-day workshop, run in partnership with Malaysian Digital Economy Corporation (“MDEC”), consisted of a series of training modules on topics such as fintech and entrepreneurship at Ant Financial’s headquarters in Hangzhou. The program also included site tours to Freshippo, Alibaba’s grocery chain, which leverages new retail technologies to converge online and offline shopping, as well as Alibaba’s Xixi Campus.

Sabrina Peng, Vice President of Ant Financial, said, “In China, inclusive financial technologies have unlocked many growth opportunities for consumers and small businesses. We are very pleased to see a growing number of entrepreneurs from Southeast Asia demonstrate real interest in learning how to be more successful in the application of digital technology to better serve consumers and empower their growing businesses. For this workshop we have had the pleasure of partnering with MDEC who share our vision and see the importance of knowledge and experience sharing to boost economies in Southeast Asia. We intend to host more of these programs to play a part in building the region’s digital ecosystem and providing opportunity to all of those business leaders who want to take it.”

“MDEC is the agency responsible for leading Malaysia’s digital economy development and one of our key pillars is helping Malaysian tech companies grow into global players,” said Dato’ Ng Wan Peng, Chief Operating Officer of MDEC, “We are very happy to partner with companies that are promoting financial inclusion, and which gives entrepreneurs a platform to expand both in Malaysia and the wider region. This also gives an opportunity for participants to exchange new ideas and inspirations with leading experts in the field as well as counterparts from other Southeast Asia countries, to empower them and enhance connectivity.”

June 2019 – MYbank, a leading online private commercial bank in China with a focus on SME financing, today announced that the bank’s Star Plan has enabled MYbank, with its financial institution partners, to serve over 15 million small and micro enterprises. SMEs are key drivers of economic growth and this partnership is now serving more SMEs than any other in the world. The announcement comes on the day that MYbank celebrates its 4th Anniversary. MYbank’s Star Plan was announced on June 21, 2018 with the aim of using technology to enable 1,000 financial institution partners to provide more cost-effective financing services to 30 million SMEs in China within a three-year period.

A little over a year later and the Star Plan is showing significant progress. As of June 2019, leveraging Alipay’s AI, computing and risk management technologies, MYbank has worked with over 400 financial partners to provide business loans of over RMB 2 trillion (USD 290 billion) to a total of 15.74 million SMEs in China. “After MYbank had been operational for a year in 2016, we were serving 1.7 million SMEs,” said Simon HU, Chairman of MYbank. “Today we serve over 15 million SMEs by combining our strength in risk management technologies with the capital support of our financial institution partners. As the Star Plan progresses, we look forward to increasing the inclusivity of financial services for SMEs by sharing our technologies with more financial institution partners.”

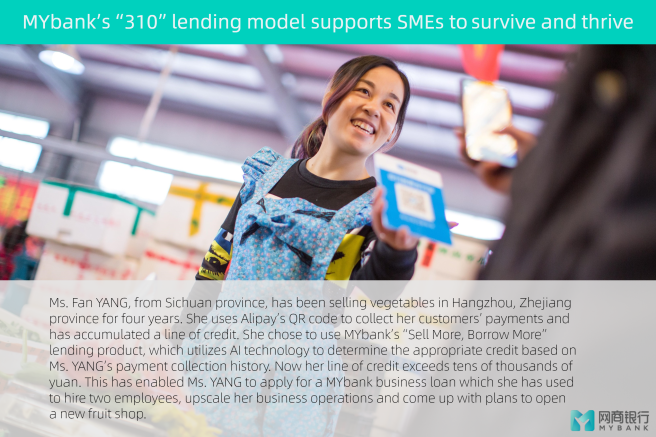

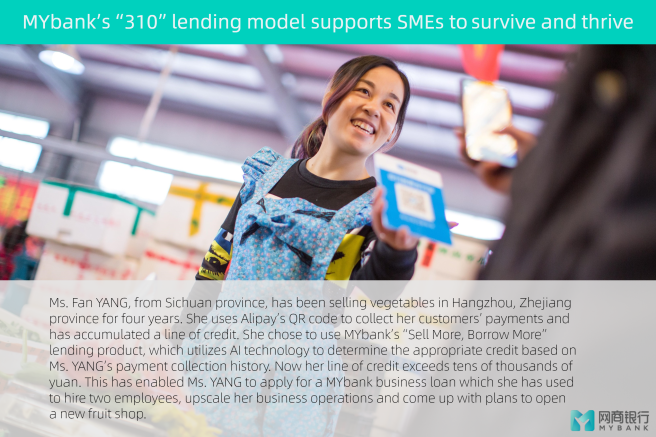

According to China’s State Administration there were approximately 73 million SMEs in China, but this large market that has the potential to drive economic growth is not receiving the financial support it needs. Toward Universal Financial Inclusion in China, a joint report published by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) and the World Bank in 2018, found that only 14% of China’s small businesses have access to loans or line of credit, compared to an average of 27% of small businesses across all G20 countries. The report highlights a number of reasons why SMEs do not apply for credit including a complex application process, perceived high costs associated with obtaining a loan, an inability to obtain sufficient loan size and maturity, as well as a long review and approval period. MYbank pioneered the “310 model” for SME financing which offers a collateral-free business loan that takes less than three minutes to apply for on a mobile phone, less than one second to approve and requires zero human intervention. Using proprietary AI and risk management technologies, the non-performing loan (NPL) ratio for MYbank’s SME business loans has consistently been at around 1%. As of March 2018, the average NPL for SME loans in China was 2.75%, according to the PBOC.

Using a comprehensive AI-powered risk management system, which comprises of over 100 predicative models, 3,000 risk profiles and more than 100,000 metrics, MYbank calculates an appropriate line of credit for SMEs that minimizes the risk of excessive lending. As a result, the non-performing loan (NPL) ratio for MYbank’s SME business loans has consistently been at around 1%. As of March 2018, the average NPL for SME loans in China was 2.75%, according to the PBOC. As of June 2019, MYbank has provided micro loans totaling over RMB 2 trillion (USD 290 billion) to over 15.74 million small and micro enterprises and entrepreneurs in China. The size of each loan is around RMB 10,000 (USD 1,500), reflecting the inclusive nature of MYbank business loans.

Over the years, Alipay has evolved from a digital wallet to a lifestyle enabler. Users can hail a taxi, book a hotel, buy movie tickets, pay utility bills, make appointments with doctors, or purchase wealth management products directly from within the app. In addition to online payments, Alipay is expanding to in-store offline payments both inside and outside of China. Alipay’s in-store payment service covers over 50 countries and regions across the world, and tax reimbursement via Alipay is supported in 35 countries and regions. Alipay works with over 250 overseas financial institutions and payment solution providers to enable cross-border payments for Chinese travelling overseas and overseas customers who purchase products from Chinese e-commerce sites. Alipay currently supports 27 currencies.

Nov 2019 – Xiang Hu Bao, an online mutual aid platform introduced by Alipay, has attracted over 100 million participants since it was launched just over a year ago, helping health protection in China become more inclusive by making it more accessible especially for the lower income and those living in rural areas. As of November 22, 2019, more than 10,000 people have received financial aid for their medical needs through Xiang Hu Bao, contributed by other participants in the platform. More than two thirds of Xiang Hu Bao participants earn below RMB 100,000 (US$ 14,000) per year, while a third of them come from rural China. Xiang Hu Bao, which literally means “mutual protection”, was launched in October 2018 and provides its participants with a basic health plan against 100 types of critical illness, including thyroid cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, critical brain injury and acute myocardial infarction. All participants share the risk of becoming critically ill and bear the related medical expenses as a collective. While Xiang Hu Bao is not a health insurance product, it complements premium health insurance offerings in the market that have wider range and depth of coverage. “Xiang Hu Bao was designed with inclusiveness in mind,” said Ming Yin, Vice President of Ant Financial. “We hope Xiang Hu Bao can support participants to help one another by providing a trustworthy platform in addition to the medical care protection provided by China’s social security and premium health insurance companies.”

Pony Ma is the founder, president, chief executive officer, and executive board member of Tencent Holdings, Ltd., one of the most important telecommunications companies in China. Tencent, with its well-known penguin icon, controls China’s largest instant messaging (IM) service and has expanded to other mobile telephone and internet services. Ma’s interest in Tencent has made him quite wealthy, and he is regarded as one of China’s most desirable bachelors. Born around 1971, on the island of Hainan, China, Ma uses the nickname “Pony” which is derived from the English translation of his family name, which is “horse.”

Pony Ma is the founder, president, chief executive officer, and executive board member of Tencent Holdings, Ltd., one of the most important telecommunications companies in China. Tencent, with its well-known penguin icon, controls China’s largest instant messaging (IM) service and has expanded to other mobile telephone and internet services. Ma’s interest in Tencent has made him quite wealthy, and he is regarded as one of China’s most desirable bachelors. Born around 1971, on the island of Hainan, China, Ma uses the nickname “Pony” which is derived from the English translation of his family name, which is “horse.” end, he and four friends founded Tencent in 1998. They began the company with only $120, 000, primarily garnered from money earned while playing the stock market. The first years of the company were difficult. Ma had to wear many hats in the first year, from janitor to website designer, as the company lacked experienced employees and financial health.

end, he and four friends founded Tencent in 1998. They began the company with only $120, 000, primarily garnered from money earned while playing the stock market. The first years of the company were difficult. Ma had to wear many hats in the first year, from janitor to website designer, as the company lacked experienced employees and financial health.

Alibaba, an e-commerce juggernaut matched in size only by Amazon. Mr Ma, who launched Alibaba from a small apartment in Hangzhou in 1999, is an emblem of China’s extraordinary economic transformation.

Alibaba, an e-commerce juggernaut matched in size only by Amazon. Mr Ma, who launched Alibaba from a small apartment in Hangzhou in 1999, is an emblem of China’s extraordinary economic transformation.

On 9 January 2017, Ma met with United States President-elect Donald Trump at Trump Tower, to discuss the potential of 1 million job openings in the following five years through Alibaba’s interest in the country. On 8 September 2017, to celebrate Alibaba’s 18th year of establishment, Ma appeared on stage and gave a Michael-Jackson-inspired performance. He performed part of “Can You Feel The Love Tonight” at the 2009 Alibaba birthday event while dressed as a heavy metal lead singer. In the same month, Ma also partnered with Sir Li Ka-shing in a joint venture to offer a digital wallet service in Hong Kong. Ma announced on 10 September 2018 that he would step down as executive chairman of Alibaba Group Holding in the coming year. Ma denied reports that he was forced to step aside by the Chinese government and stated that he wants to focus on philanthropy through his foundation. Daniel Zhang would then lead the way ahead for Alibaba as the current executive chairman.

On 9 January 2017, Ma met with United States President-elect Donald Trump at Trump Tower, to discuss the potential of 1 million job openings in the following five years through Alibaba’s interest in the country. On 8 September 2017, to celebrate Alibaba’s 18th year of establishment, Ma appeared on stage and gave a Michael-Jackson-inspired performance. He performed part of “Can You Feel The Love Tonight” at the 2009 Alibaba birthday event while dressed as a heavy metal lead singer. In the same month, Ma also partnered with Sir Li Ka-shing in a joint venture to offer a digital wallet service in Hong Kong. Ma announced on 10 September 2018 that he would step down as executive chairman of Alibaba Group Holding in the coming year. Ma denied reports that he was forced to step aside by the Chinese government and stated that he wants to focus on philanthropy through his foundation. Daniel Zhang would then lead the way ahead for Alibaba as the current executive chairman.