The fundamentals of the problem.

What has gone wrong? Until the mid-1990s, Australia had a reputation as a well-housed, affordable country for ordinary citizens, notwithstanding the enduring concentration of poverty among lower income private renters and those missing out on the benefits of tenure security and wealth creation delivered through mass home ownership. Nonetheless, Australia sustained a high level of home ownership of around 70% of households, consistently rating in the top cohort of developed countries. Since the mid-1990s, however, the Federal housing department was reduced to a branch within the social security ministry; there is no dedicated national minister for housing; national monitoring of supply and demand conditions in the housing market was abandoned; and social housing funding cut, curtailing additional supply. Australia is bereft of a dedicated national approach to home ownership and housing security and affordability. Until relatively recently the average Australian family could expect to buy a home on one wage, with prices three times the median household income. Australia was one of the world’s great home ownership societies for working people. Since the early 2000s owning a home has become extraordinarily difficult for millions of working Australians, particularly younger citizens. Further, the proportion of owner-occupied dwellings is at its lowest point since 1954. Precipitous falls in home ownership rates for young adults and long-term declines in home ownership affordability rank among the most severe in the OECD. Home ownership rates are naturally higher for older generations as they have more time to save a deposit. Yet there is a widening wealth gap between generations, as asset prices rise faster than wages and record-low interest rates boost house prices. Housing unaffordability is a long-run problem, driven by speculative investment via well-publicised tax distortions, high capital inflows from foreign investment, and consistently record levels of immigration clustered in Australia’s capital cities, and to an extent supply issues such as land availability. Australia’s housing system is not a symptom of inequality – it’s the main driver. Young people who can access the housing market as first time buyers often have a leg up from parents, perpetuating inequality across generations while property wealth creates an asset against which owners can borrow to buy more. While most investors only own one

property, there has been rapid growth investors with more than one property, and private renters are just

as likely to be renting from someone who owns more than one property.

Australia’s retirement incomes system was constructed on the ‘three pillars’ model. Along with voluntary

savings, compulsory saving [superannuation] and the pension, policy settings assume that most retirees

own their home outright and thus have minimal housing costs in retirement. Recent evidence undermines

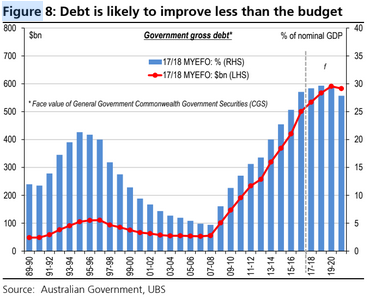

this model. AHURI research shows that the proportion of homeowners aged 55 to 64 years still owing

money on their mortgages has more than tripled; from 14% in 1990 to 47% in 2015. According to recent

ABS Survey of Income and Housing data, home-ownership rates among Australians aged 55-64 years

dropped from 86% to 81% between 2001 and 2016, and older Australians are also shouldering high levels of mortgage debt in later life: in 2001 roughly 80% were mortgage-free, but fifteen years on this had

plummeted to only 56% and indebtedness is growing among homeowners aged 65 and over. In 2001, nearly 96% of this cohort were mortgage-free. By 2016, however, of that cohort the proportion fell to below 90%. The number of outright owners aged 55-64 is expected to fall by 42%, from more than 1.2 million to 708,000. Conversely, the numbers of older mortgagors and older private renters is projected to soar. All this will have a significant impact on cost of living in retirement and will grow with each successive generation. This will also place added burden on public and community housing, as well as expanding the numbers eligible for Commonwealth Rent Assistance, placing additional strain on the commonwealth budget. AHURI research suggests that due to tenure and demographic change, CRA demand will rise by 60%. Housing stress must be addressed as a matter of urgency by the commonwealth if the national economy is to recover. Making housing more affordable, its supply more effective and targeted, and lifting home ownership rates, can and must be done in tandem with making the renting experience better. As it stands, Australians are covered by a patchwork set of state and territory government laws covering the rights and responsibilities of people renting privately. While progress on rental rights has been made in several jurisdictions, there is a need for a national conversation over how Australia deals with the structural shift to higher and more permanent numbers of renters, considering economic and community costs. The residential housing market [RHM] is far too important to be left in the hands of a bunch of unprincipled criminals otherwise known as commercial bank management.

The Hayne Royal Commission identified scores of individuals who were responsible for a number of

horrendous acts perpetrated by banks [mostly those called ‘the big four’] but, because of the power

wielded by these organisations, both politically and economically, very few if any, have suffered any penalty. The whole system needs restructure; fiddling at the edges will not bring about change. What follows are some ideas that will alter the RHM to the benefit of both the Australian economy and Australian home owners.

Over the last 20 years, house prices have grown on average by 7.2% a year, a $7.1 trillion increase.

Government policy in the form of preferential tax treatment and incentives for property assets, is often

asserted as the main reason for this growth. The RBA, however, has published estimates that the capital

gains tax exemption and negative gearing combined account for less than 2% of the multi-trillion-dollar

recent growth in house prices. The same report also observed that first home buyer grants had an

insignificant effect on price over the long term, and so did not merit factoring into pricing analysis. Foreign investment represents a small proportion of Australia’s residential real-estate transactions, with foreign owner accounting for just 1.8% of buyers and 0.5% of sellers in 2019-20. Foreign purchases were

overwhelmingly concentrated on new build properties [typically apartments] which represented 57% of all

foreign investment property transactions. Part of the general misconception about the importance of

interest rates in driving Australian house prices over the long term comes from a belief that property is a

highly levered asset class, and so more sensitive to rates than other assets. Yet debt accounts for only 20%

of the equity in the Australian residential property market. Indeed, house prices have grown consistently over the last 60 years at an average rate of approximately 7% [without any reductions lasting more than a year] even as the RBA cash rate has varied significantly over the same period. Figure 5 shows the change in interest rates over periods of house price doubling.

House prices doubled four times between 1960 and 1988 as interest rates rose and continued to double as interest rates fell between 1988 and 2021. This suggests that house price growth is occurring independently of interest rate movements over the long term. These figures suggest that we must look beyond the role of interest rates to fully understand what drives house prices in Australia over the long term.

Land plays a significant role in driving house price growth due to unique features that distinguish it from

other investments. Unlike other things for which there is a market, there is a fixed supply of land, and each parcel of land occupies a unique location. Also, everyone needs somewhere to live, making land different from other goods where, if the price gets too high, people can opt out of using them. Australia has an abundance of land, but there is a limited – and fixed – supply of serviced land. Population growth makes all well-located suburban land scarce, especially along transport corridors and relatively affordable outer suburban locations. When a good or service is scarce, we expect its value to increase. The gap between house and unit prices is steadily increasing in Australian cities. We can see this relationship in Melbourne [Figure 15] where freestanding houses have grown at 7% annually followed distantly by townhouses, medium density apartments, and high density apartments. Because the amount of land within each type of property follows a similar pattern, there is good evidence to suggest that the difference in price growth over the long term is driven primarily by land. The same methodology shows similar patterns in all our major cities. Residential land makes up an increasingly large proportion of Australia’s national net worth. It’s estimated that 48% of Australia’s total national assets currently consists of just residential land, compared to 34% in 2012 [Figure 17].

Critically, residential land eclipses all other Australian asset classes in scale, including physical residential structures, commercial real estate, bonds, and equities. Unfortunately, once constructed, these assets are unproductive and act as a drag on the GDP. Also, having so much of national wealth tied up in unproductive assets causes an over reliance on resources as the base for GDP. As property prices have grown, so too have proportionate costs like council and insurance rates [which grow based on property value] and transaction costs like stamp duty. Rising house prices don’t automatically improve a homeowner’s ability to buy a better house [since the prices of all properties are increasing] and they mean that the cost of owning a house of the same quality is increasing. This phenomenon is particularly harmful for low-income homeowners like pensioners who might own a property outright but lack the ability to service these ever rising proportionate and transactional costs. Thus paradoxically, many low-income homeowners are being disadvantaged by Australia’s long term housing growth.

Crucial Steps.

Financial deregulation has been disastrous. Since its advent, banks have raised fees and charges, cut

services and exploited their collective monopoly power whenever possible. The Federal Government must

instruct APRA to bring immediate legal proceedings against all of the criminals exposed in the HRC and,

pending the outcomes, further protect customers by revoking some banking licences. It could ‘renationalise’ CBA by replacing small shareholdings and superannuation fund holdings with bonds at face value and instruct the Future Fund to purchase the remaining shares at a significant discount to face value. The investment part of the bank should then be sold off and local CBA branches report to regional offices that had representation from local communities included in their decision making capabilities.

In this way the existing infrastructure of the bank could be utilised by the regional offices to provide an

efficient, community focused source of investment and loan funds. Only when based on small, member

owned or community run organisations, will some common sense be returned to the banking system – back to the good old days when Australia had a peoples bank. The current regulators, major existing players, and even Treasury will resist reform, but the case for reform is overwhelming. Bad behaviour should be easier to identify and manage, productive lending should be encouraged, customer pricing should be more transparent, and systemic risks should be better managed, alleviating the need for bank bail-in during difficult times. In a recent submission to a Senate inquiry the Citizens Electoral Council wrote:

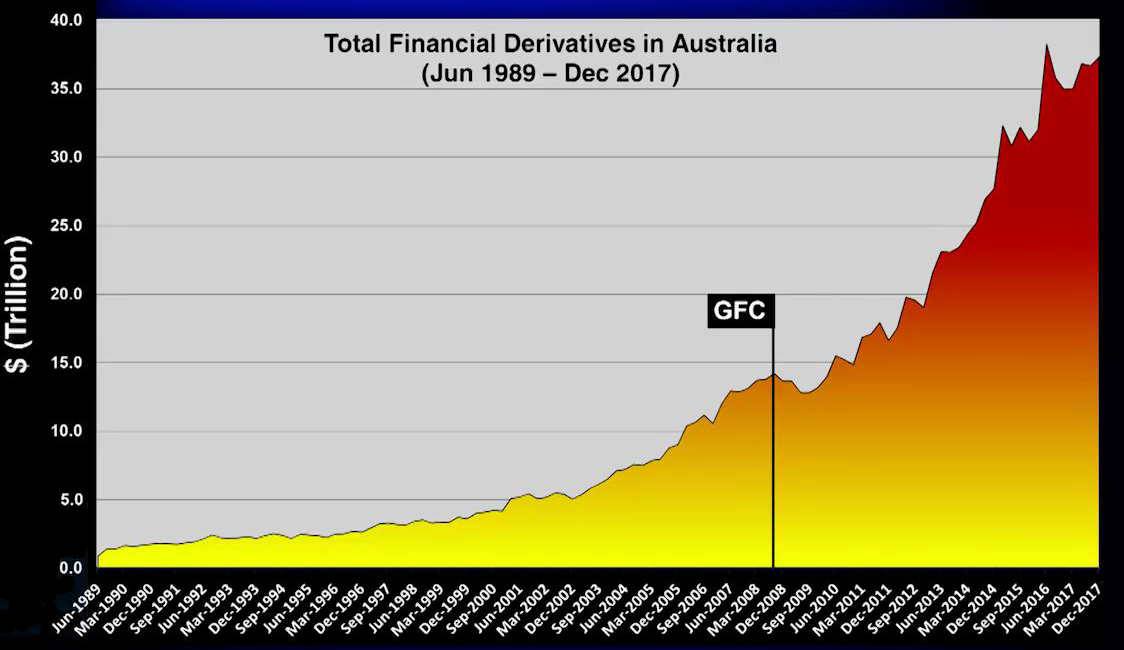

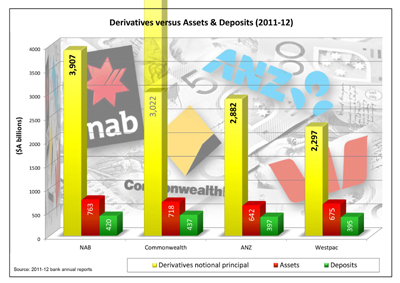

… we hold the view that the major financial sector players are too complex to be managed

effectively, scale is now a disadvantage. Thus, we believe there is a case to break up the banks into

smaller units. This would involve both vertical disaggregation [separation of advice, sales and

product manufacture] and horizontal disaggregation [separate of wealth, insurance, retail banking

and investment banking]. In addition, there are significant risks from their operations in derivatives,

and in an integrated environment, costs, risks and profits are cross linked. Given the size of the

derivatives sector [significantly larger than before the GFC], the systemic risks are significant. To

counter this, we advocate the implementation of a modern Glass Steagall separation, where the

high-risk speculative activities are separated from the normal lending, payment and deposit

functions within banking. This would have the added benefit of reducing the potential risks of a

bank deposit bail-in in a time of crisis. Evidence suggests that the existence of a modern separation

would reduce risk and limit systemic risk. In a post Glass Steagall world, bank lending would be

more aligned with the deposits available, so their ability to make loans ‘from thin air’ as in the

current system would be curtailed. They would also be more inclined to make loans for truly

productive purposes.

Step 1.

The RBA can’t really make the economy dance to its tune by simply setting interest rates. It only sets the

notional rate, it’s up to the commercial banks to determine the actual rate that affects the RHM. Therefore

it is crucial to remove as many mortgages from the unrestrained commercial banks as possible in order to

reinstate some degree of sanity to the market. The first step must be the re-nationalisation of the

Commonwealth Bank of Australia. This radical action will go a long way to breaking the monopoly of the

existing ‘big four’ [ANZ, Macquarie, NAB and Westpac] allowing a more equitable, less expensive method of financing residential real estate. The intent of splitting the RHM into two, owner/occupier and investment, with different mortgage conditions applying to each, will go some way to giving back to the RBA the control of interest rates it needs to better manage the economy. All loans made to PPR owners should be non recourse. A recourse loan allows a lender to pursue additional assets when a borrower defaults on a loan if the debt’s balance surpasses the collateral’s value. A non-recourse loan permits the lender to seize only the collateral specified in the loan agreement, even if its value does not cover the entire debt. The loan agreement will specify that the lender can seize and sell specific property or properties of the borrower to recoup losses in case the loan defaults. There can be no argument for some one who has just lost their home being saddled with a massive debt. This will also mean that lenders will have to improve their due diligence.

Allowing the commercial banks to establish the ‘cost of money’ [as an interest rate is called] is simply a

mechanism for inflating profits. The cost of administration of a loan is similar, regardless of the amount

involved. Hence the differential between savings account rates, approximately 1% and current loan rates of 6% and rising, simply penalises later entries to the market who have had to borrow a much greater

proportion of the purchase price. By linking the admin fee to a borrowers income it makes it easier for

social service recipients, pensioners and other low income workers to afford a loan. Reducing the margin

between deposit rates and loan rates will reduce the banks profits, hopefully thereby driving down the

share price. The Commonwealth government has a number of options to compulsorily acquire 51% of CBA shares and replace the current board of incompetents with local appointees who actually know how to run an ethical bank that services the community. One option would be to restrict shareholding to Australian companies and residents. Large shareholdings such as Vanguard could be transferred to Industry Super funds. Australian finance history buffs would be familiar with the so-called 30/20 rule in place from 1961 to It required Australian life insurance and superannuation funds to invest 30% of their assets in state government bonds and 20% in Commonwealth government bonds in order to qualify for income tax exemption. A similar scheme could be introduced to fund shareholding in the ‘new’ CBA. Once established, the new CBA state branches will invite Principal Place of Residence [PPR] owners in their region to switch their mortgage to CBA [using a digital platform such as PEXA]. Instead of charging interest the bank will levy a flat fee commensurate with the income of the family using ATO income tax brackets. E.g. up to $18,200 fee is nil. Up to $45,000 – $250/month. $120,000 to $180,000 – $500 per month etc. etc. In this way the interest rate charged on a PPR mortgage would be independent of the RBA, less volatile thus leading to borrowers being able to better budget.

Step 2.

The Australian private rental system represents a significant portion of the housing market. More than 26% of all households in Australia rented privately in 2021, totalling more than 2.9 million households. The deteriorating affordability of housing has led to an increasing number of individuals renting on a permanent basis – 43% of renters have been renting for a decade or more. In Australia, rental properties are primarily owned by individual investors, an estimated 2.2 million Australians. Most rental properties are owned by individual investors who own only one or a few investment properties in what has been described as a ‘cottage industry’; 71.5% of investors own one property, 18.8% own two, and 9.7% own three or more. Ownership of investment properties is also highly fragmented among many different demographics with diverse motivations, circumstances, and needs. Rental prices have significantly increased over the past three decades, outpacing inflation. Rent is increasingly unaffordable for lower income households, which include some of Australia’s more vulnerable demographics. These include the recipients of government stipends, single parent households, and older households. One of the biggest challenges for lower-income renters is finding a rental property at all. It is generally harder for these households to obtain accommodation because property managers are likely to preference higher income applicants. Australia is one of the hardest places in the developed world to be a renter. The biggest challenge renters face is insecurity; long term leases are rare, and renters live with constant uncertainty about whether they will have to move. Few private renters stay in the same property for more than five years, with the majority moving frequently. Further, rental quality is often poor. Maintenance is often a headache to organise and there are few incentives for the landlord to improve the quality of rental properties more broadly. Renters often have limited ability to make minor alterations. These factors together make it difficult for renters to make a home out of their rental accommodation.

Investing in property is often perceived as a symbol of security, a tangible source of retirement income, and a legacy to pass on to future generations. Residential property is also one of the few asset classes that can be interchangeably used both personally [to live in] and for investment purposes [to rent]. In this way, property investment is for many people an emotional decision as well as a financial one. Yet property

investment is often complex, stressful, and risky. It can be much more time-consuming than expected, and unanticipated maintenance costs are not uncommon. Since 1990, approximately 60% of all property

investors would have profited more by investing in superannuation. Such difficulties partly explain why half of all investment properties exit the rental market within five years. With sale being the most common reason for landlord-initiated lease terminations, the poor experience of landlords is closely related to the insecurity that underpins poor rental experiences. Solutions to these challenges need to break the current nexus between landlords and renters, to create a system that can work for everyone.

The size of Australia’s housing market, and the difficulties governments have in addressing housing crises at sufficient scale, offers an opportunity for private capital to provide solutions. Private capital in Australia falls into three groups:

- Major investment groups: Superannuation funds and investment banks

- Smaller investment groups: Family offices and other smaller-scale funds

- Individual investors: High net worth individuals and ordinary property investor.

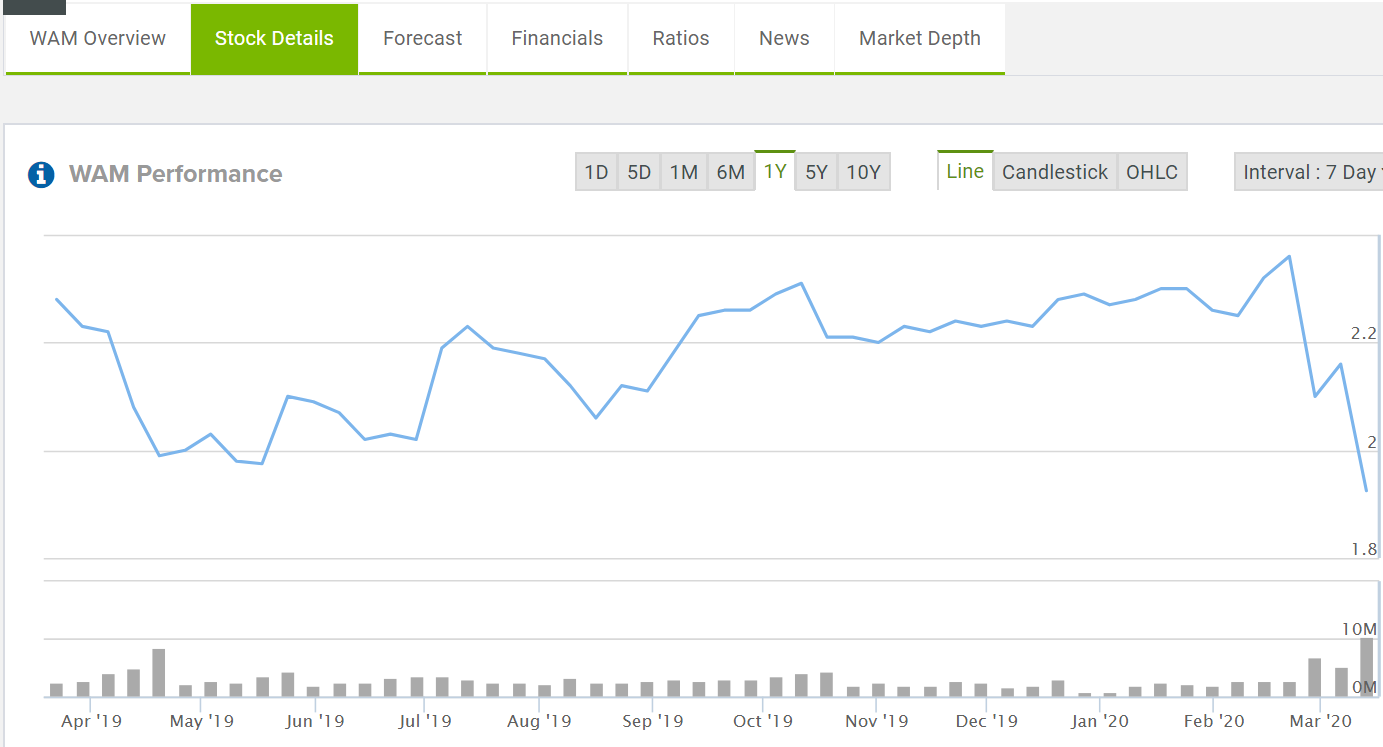

Each of these groups has their own reasons for investing in property. The first group invests in property for risk management, diversification, and low volatility. Family investment managers typically invest for historically strong growth and as a stable store of wealth. Individuals often invest due to familiarity, non-volatility, concern about the volatility of other asset classes [for example the share market], and preferences for physical assets that feel more secure than other equity types. Improved financial literacy amongst individuals [e.g. explaining why it’s better to gear property ETFs that produce franked dividends] would go a long way to overcoming he fear of volatility. When discussing private investment in Australia, most of the discussion, and certainly most policy emphasis, is placed on the first of these groups – notably large superannuation funds. The Federal Government has recently announced a major push to work with superannuation funds to engage with the Australian housing sector, as they currently have very little exposure to Australian residential property, particularly considering their size and the size of the asset class. But a much larger source of capital also lies in the third group, where Australia’s two million individual property investors account for ownership of 26% [approximately $2.5T] of Australia’s $9.8 trillion residential property market and unlike superannuation funds, have already chosen the residential property asset class.

Shared Equity models involve a third-party investor co-investing in a property with a homeowner in

exchange for a share of a property’s capital growth. These programs enable buyers to buy properties with

lower deposit savings. They can also result in lower monthly mortgage payments, allowing owners to share financial risk with third parties. Shared Equity programs exist in Australia at both State and Federal

government level. The model has an extensive history overseas, mostly funded by governments to improve housing affordability, but also by private sector organisations to achieve commercial outcomes.

Build to Rent is a model in which developers build properties, often high-density apartments, without the

intention of selling them individually. Instead, these properties are held by the developers or a wholesale

purchaser and offered for rent indefinitely. So far in Australia, BTR has targeted the premium rental market. The model has also gained attention as a way of increasing housing supply, with governments hoping that for a trickle-down effect on the rent prices overall. As a result, various tax breaks have further encouraged the growth of these models in recent years. BTR tenants enjoy much better tenure security than other types of rental accommodation. BTR models are generally well maintained and professionally managed, as should be expected for their premium price point. Together with the availability of high quality common spaces and facilities, this means that BTR users often enjoy good tenure security and experience, representing a strength of premium-rent BTR models in their early years. Over time, as premium rents become more difficult to sustain as the building and facilities age, it might become more challenging to provide good a rental experience, particularly if building owners change.

Not-for-profit community housing providers offer existing properties through an investment structure

focused on acquiring portfolios of residential property which are held in trust and offered for rent. The

community housing sector is a long standing and vital component of the Australian housing system and

receives government funding to help address affordable housing shortages across the country. Over

100,000 Australian households currently live in community housing-owned and managed homes with

subsidised rent, based either on a discount to the market rent or as a percentage of household income.

Easing the pressure on the private rental market can also be informed by developments in the community

housing sector and best-practice coordination between different layers of government. Community housing should be seen as complementary to public and private, for-profit initiatives and the existing stock of state run public housing. It has underpinned the growth and viability of the fairest and best-performing social housing systems in the world such as Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands. In this model, management and/or ownership of land, including land owned by the state, is vested in not-for-profit community organisations aimed at long-term affordability and tenure security akin to public housing. Management thus can be run along the lines of innovative cooperatives and housing trusts. Providers are innovative, flexible not-for-profits who have taken calculated risks and proven adept at responding quickly to the needs of residents. One reason for this flexibility is that, unlike government instrumentalities, community providers can borrow against their assets – allowing the NGO sector to monetise existing assets in ways that are consistent with broader public benefit. The federal government’s National Housing and Finance Corporation’s strategy of offering community housing agencies access to lower-cost loans is a positive development by which this sector might form one part of the national jigsaw of housing affordability. The aim is to split the nexus between ownership of the building and the land. The building can be rented, subject to shared equity or purchased but the land must remain in the ownership of the Community Land Tenure body. In this way speculative pressures are removed and the land should remain relatively constant in value.

Step 3.

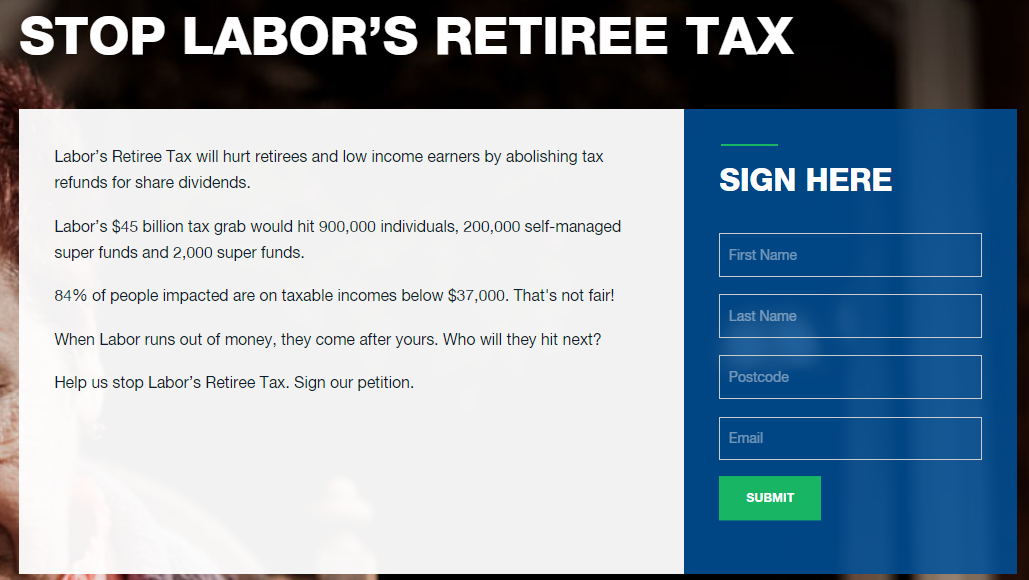

To address rental stress, the federal government, through the existing mechanism of Commonwealth Rental Assistance [CRA], should permanently increase the levels of rent assistance to eligible, lower income individuals, women [especially targeted at those aged 55 and above] and families. Specifically, CRA should be substantially increased, and indexed to changes in the rents ordinarily paid by recipients, so that its real value is preserved over time, [recommended by the Henry Tax Review]. Higher CRA payments will be necessary if, as predicted, more and more older Australians do not own their homes and are renting in retirement. Strategically paired with investment in build-to-rent and build-to-rent-to-own, and expansion of community and public housing, this structural change to renter’s income would have the added benefit of attracting investment into affordable housing by generating a more acceptable rate of return to investors. Long overdue changes to negative gearing and capital gains tax would save the Government about $5 billion a year. The interaction of a fifty per cent capital gains tax discount with negative gearing distorts investment decisions, makes housing markets more volatile and reduces home ownership. The two measures in combination allow investors to reduce and defer personal income tax, at an annual cost of $12 billion to the public purse. And like most tax concessions, these tax breaks largely benefit the wealthy. The capital gains tax discount should be reduced from 50 to 25 per cent, and negatively geared investors should no longer be allowed to deduct losses on their investments from labour income. The reforms would provide relief to the Budget in tough times and slightly improve housing affordability with little impact on how much people save. Contrary to urban myth, rents won’t change much, nor will housing markets collapse. The effects on property prices would be small compared to factors such as interest rates and the supply of land. The reforms should be phased in, to make them easier to deliver and to prevent a rush of investors selling property before the changes come into force. While other proposals, such as restricting negative gearing to new properties or limiting the dollar value of deductions, would improve the current regime, they nevertheless leave too many problems in place and introduce unnecessary distortions. Abolishing negative gearing should cause a large proportion of owners of investment properties to reconsider owning residential real estate as an asset and should result in many properties being put on the market, leading to a decrease in price. Distress sales will provide opportunities for alternative ownership vehicles such as SE, BDR and CHP to purchase a portfolio of properties that can provide the benefits that accrue from each model, at the same time constraining speculation and inevitable increase in prices. Here again, the an education campaign is necessary to convince PPR owners that a reduction in capital value on a property that is not going to be sold. The big four banks are largely owned by [the same five or six] overseas investment banks and listed equity funds [Google top ten shareholders], and the majority of dividends go offshore. Hence the benefits of holding a license [Federal deposit insurance, ‘bail-in laws etc.] are provided at tax payer expense without commensurate benefits. The way to rectify this situation is to impose a ‘turnover’ levy where each transaction is levied a tiny fee.

Updating legislation that unmasks real estate transactions that are being used to launder ‘dirty’ money,

particularly from overseas, is crucial to solving the problem. The Australian Institute of Criminology

estimates that serious and organised crime costs the Australian community up to A$60.1 billion in 2020-21, with illicit financing at the centre of most crime types. It directly impacts the safety and wellbeing of

Australian communities, and exploits and distorts legitimate markets and economic activity. The AML/CTF

regime is a central part of Australia’s efforts to prevent criminals from enjoying the profits of their illegal

activity. Since 2006, those ‘Tranche 2’ federal money-laundering law reforms have been hand-balled from

one incoming government to the next. Out of more than 200 jurisdictions, Australia is now one of only 5

jurisdictions in the FATF Global Network, alongside China, Haiti, Madagascar and the United States, that do not regulate tranche-two entities.

Appendix 1.

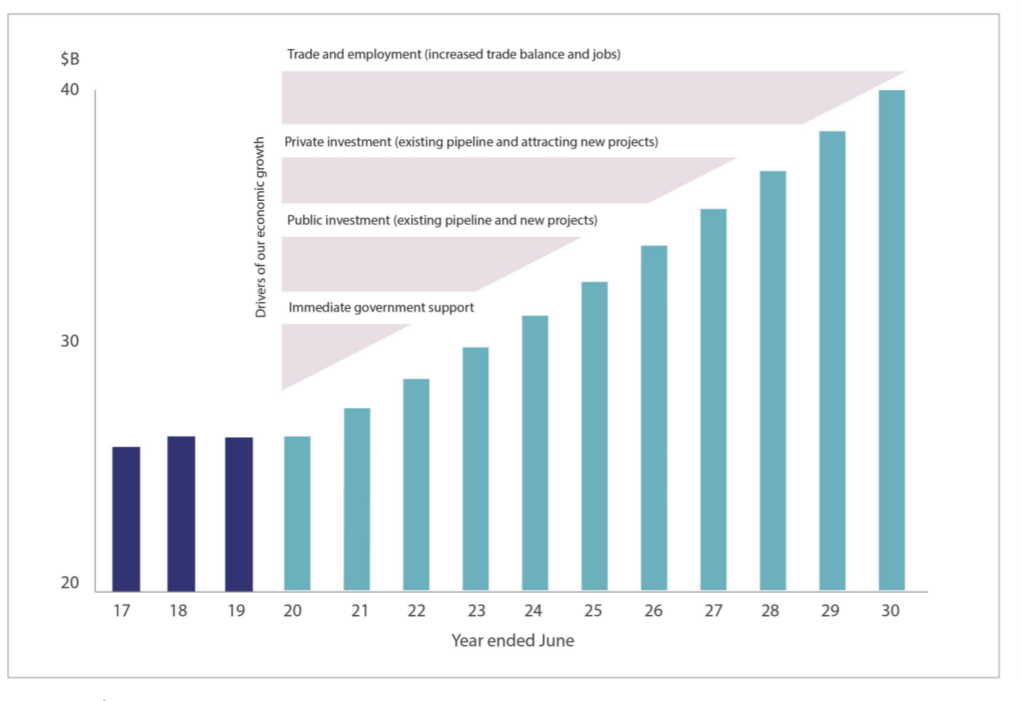

Australia’s current housing crisis is driven by the nation’s unique demographics and a shortage of

available residential land near jobs and services, with the impact of interest rates and government

home-buyer subsidies often overstated. These are the central of findings of a new analysis of

Australia’s housing affordability and rental crises, which goes on to warn that without change, the

disparity between those benefiting from the property market and those falling behind will only

worsen. LongView and PEXA have released a three-part series that explores the origins of the

housing crisis – for buyers and renters – and looks to offer fresh solutions. Most of the charts and

data relating to the residential housing market are sourced from these whitepapers. LongView |

PEXA Whitepaper – What drives house prices in Australia?

Appendix 2.

The privatisation of the Commonwealth Bank was a financial disaster for the Australian public,

although investors in the float did very well indeed. Prior to the sale of the first tranche of shares in

1991 involved the issue of 835 million shares at par value $2, the with an issue price which was set

at $5.40. The second tranche of shares in 1993 ensured that the government received an amount

close to the market price of the shares. The total proceeds from the three stages of the sale

amounted to about $7.8 billion in 1995-96 dollars. Primarily because of the removal of restrictions

on the monopoly power of the banks, profits have soared. Profits, paid to shareholders for 2023 are

expected to be about $10 billion, or more than the total sale proceeds received by the Australian

public. As the bank marks a quarter of a century as a listed company, shareholders are sitting on

hefty gains in their investment. They should be encouraged to sell at a much lower price to the

proposed HFF or some other Government fund.

In mid-2015, 11 Commonwealth Bank accounts were opened in 11 different names. Eleven different

New South Wales drivers’ licences were used to open the accounts. If anyone at the CBA had

checked, they would have noticed the pictures on most of the licences featured the same

overweight man. That man was Kha Weng Foong. AUSTRAC identified four syndicates that

deposited a total of about $90 million with the bank. The syndicate involving Foong, a Malaysian

citizen, is one of those examples and highlights the massive money laundering that slipped past the

CBA gaze. Three men deposited about $3.6 million across 427 separate transactions. They made

dozens of deposits under $10,000 at branches scattered across Sydney to avoid scrutiny. Once the

money was deposited into the accounts, Fung transferred millions to two Hong Kong accounts

across 99 separate online transactions. The three men funnelled $4.5 million out of Australia,

primarily because of lax standards at the CBA. And if AUSTRAC allegations are to be believed, it was

only the tip of the iceberg. AUSTRAC, Australian’s financial spy agency, filed a case against the CBA

alleging it failed to report 53,506 transactions. CBA submitted two records to AUSTRAC, then exactly

four weeks later, the remaining 53,503 flooded in. It was absolute pandemonium, somebody

whispered “Oh my God, look at this. It’s not just these two that are missing, it’s every transaction

since we started these machines.” The problem is that banks and all sorts of corporations over the

years have replaced human beings with intelligent machines, assuming the machines will do

everything needed. They’ve just cut down on the number of staff, the number of people who are

looking at compliance issues, and the number of people who are supposed to police and monitor

these issues, and now they’re paying the price. They are known as TTR’s, or “threshold transaction

reports”. Basically, banks have to let AUSTRAC know within 10 business days if it processes a

transaction of $10,000 or more. So how did it happen? The CBA says it all comes down to a software

error in the bank’s smart ATM’s. But what are these fancy smart ATM’s, and how could the bank

miss a coding error that has lead to a massive civil proceeding in the Federal Court?

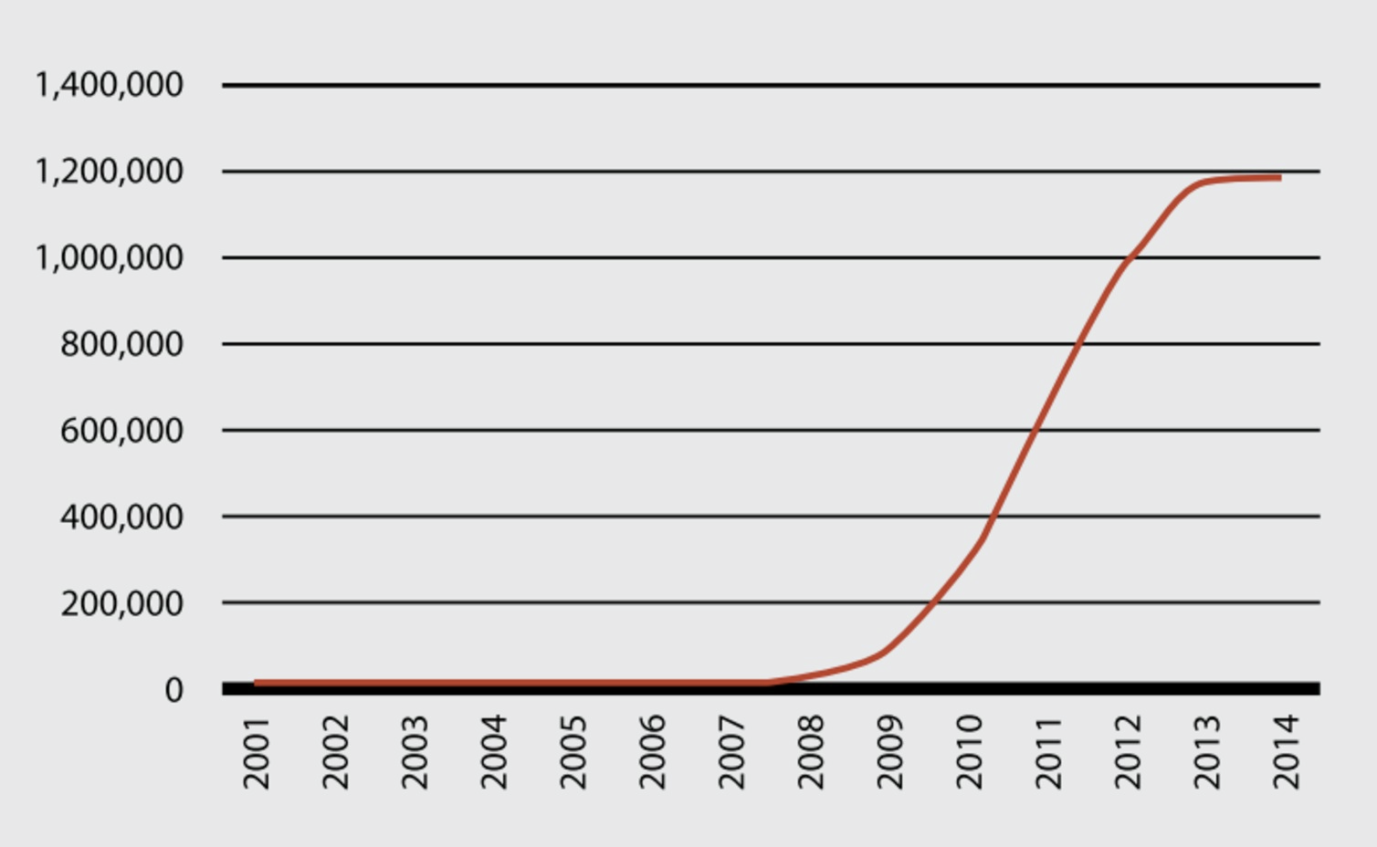

The CBA first rolled out the Intelligent Deposit Machine [IDM] in May 2012. An IDM is a type of ATM

that automatically counts the cash as it goes into the CBA customer’s account. It’s convenient and

saves the bank money, since fewer human tellers are required. But AUSTRAC alleges that CBA didn’t

limit the number of transactions a customer could make per day, and that its IDM’s allowed up to

200 notes per transaction. If you’ve got a lot of Granny Smiths [$100 notes] from an illegal drug

empire, you could put 200 into a machine at a time. That adds up to a $20,000 in transaction – well

above the mandatory reporting limit. IDM’s also allowed anonymous cash deposits, so it wasn’t long

before the system was abused by criminals; that means a criminal could potentially put millions of

dollars through a machine in one day anonymously. Not only that, but because the money appears

instantly, a user can immediately transfer the money to another account – say, one that exists

offshore. Since the CBA introduced the IDM’s, their use has grown exponentially. In May and June

2016, more than $1 billion in cash went through CBA’s IDM’s. In a statement to the Australian Stock

Exchange the bank argued that all 53,000 alleged contraventions of the code could be counted as

just one offence. It is an important distinction, because one infraction alone carries a penalty of $18

million. 53,000 of them, is a rather large fine. The ABC’s business editor called that a ‘brave’ and

‘adventurous’ argument but said the law is very clear. “Imagine if you’re caught for speeding again

and again and again, and you say, look, my speedo was broken so I didn’t know how fast I was

going, so therefore I should only have to pay the fine once, not the 450 times that you’ve caught me

speeding.’ You reckon that’d fly?” The error may have been discovered simply because the AFP

requested all deposits from a specific day, and when the bank went to look for them they realised

they weren’t there. A trillion dollars, which is a thousand billion. About seven times Banks market

value. If it comes to that, it simply won’t be able to pay. According to AUSTRAC, “the effect of

CommBank’s conduct in this matter has exposed the Australian community to serious and ongoing

financial crime”. It doesn’t get any worse than this. Banks are meant to be the watchdog for

suspicious activity involving criminals and money. For example, in the current climate it’s a key

plank in the fight against terrorism. To abrogate that responsibility is beyond belief. And yet, if CBA

runs true to form, no senior executives will be held to account for this scandal. That is, sacked. The

executive officer ultimately responsible was paid $14 million last year for a job which is effectively

government guaranteed. While no-one is suggesting he had any direct involvement in any of the

scandals which have plagued the bank under his watch, ultimately, if you are going to take the big

bucks, the buck stops with you. It’s the CEO’s job to put the people and systems in place to ensure

his company, which incidentally is Australia’s biggest, operates to the highest legal, ethical and

monetary standards. And the IDM scandal is just the tip of the CBA manure pile. The scandals of the CommInsure activities that caused the death of policy owners and the Storm Financial debacle add to the

necessity for the whole edifice to be destroyed and replaced by a new financial organisation that

can meet the needs of the residential housing market.

Appendix 3.

This is an edited extract from Nathan Lynch’s book The Lucky Laundry, published by HarperCollins,

June 2022.

Gaping loopholes, earnest advisers and an international reputation for stability have made Australia

a place of choice for illicit funds. Despite a crackdown on the foreign ownership of established

houses, there are still many ways for crooks to score a piece of the action, no matter which

government is in power. The dream of the quarter-acre block, of the double-brick cottage with a

lawn for the kids and a Hills Hoist, is now so alien as to be a parody. The ideal of a home in which to

raise a family has been overtaken by mortgages delivered by an army of ‘brokers’ from the

deregulated, globalised banking sector. Average household debt, measured against gross domestic

product [GDP], has reached an historic 123%. Australian households have been lured into one of the

greatest debt traps the world has ever seen. Most of this borrowing has not funded enterprise. It

has been borrowed to buy homes at prices that spiral ever-upwards. Modern Australians borrow

from the rest of the world to buy each other’s homes, abetted by a banking sector that clips the

ticket on every dollar borrowed when they rack up the interest bill each month.

Aussies have been good to the national housing market, investing more than $9 trillion into

residential real estate. The housing market, in turn, has been very good to Aussies. In 50 years

housing prices have multiplied more than 85 times. In 1970, the median house price in Sydney was

$18,700. Half a century later it’s $1.6 million. For those with a ‘foot on the ladder’, the family home

has become many things in addition to a place to live and raise a family. It’s an asset class, a form of

security, an ATM redraw facility, and something to show off at barbecues. It’s the pride and joy of

every Australian – and with so much wealth tied up in bricks and mortar, housing policy can also

swing elections. Despite myriad difficulties, every weekend, young Australian families bid at

property auctions against anonymous bidders and buyers’ advocates. These families bid valiantly

with a combination of their hard-earned savings, government grants, the proceeds of judicious

investments, and sometimes even gifts and inheritances from parents. The vast majority of this

money is leveraged up by the world’s most profitable banks. Aussie families use this credit to buy

into their simple dream: home ownership, financial security and self-determination. But look past

the picket fences and there is a different type of resident, a more shadowy purchaser. These owners

are often listed on property titles as companies, which are in turn the trustees of offshore vehicles

in secrecy jurisdictions like Samoa or the Cook Islands.

To a punter in the suburbs, these complex financial structures are mere ghosts. Who are these new

neighbours who have popped up all over Australia, as they have in Canada and London, with the

metaphorical lights off and blinds drawn? And what of those anonymous buyers? Who are the

people hiding behind dark sunglasses, and behind even more opaque foreign trusts, standing

discreetly at the back of property auctions? Who do those professional buyers’ agents in property

deals truly represent? In many cases, no one in Australia knows. Because no one is really required to

know. Everyone in the transaction chain [except the bankers] is allowed to turn a blind eye. They

can park their suspicion behind a thick wall of customer privacy, professional discretion and selfinterest. This is one reason why Australia is so attractive to investors who seek secrecy, discretion

and security. It’s also a primary reason that we have become one of the world’s most attractive

destinations for money launderers. Forgiving laws, gaping loopholes, earnest advisers and a

squeaky-clean international reputation have made Australia a place of choice for illicit funds.

Despite a federal crackdown on the foreign ownership of established houses, there are still many

ways for crooks to score a piece of the action. Foreign criminals and government kleptocrats can go

to town on new builds. They can jump into commercial property, farmland, dairies. In one case, the

AFP seized a 3000-acre property near Tasmania’s stunning Musselroe Bay that was linked to a $23

million investment fraud in China. With the right advice, buyers can easily conceal their ownership.

Real estate agents will happily turn a blind eye to a foreign ‘cash purchaser’ who is ready to sign a

contract; those unconditional cash deals mean the agent’s commission goes straight in the bank. In

some cases, agents have even provided fraudulent bank letters to assist a foreign buyer to move

their funds through a local proxy buyer.

Australia has become so accommodating to money launderers that countless local families have

been forced into the rental market to make room for them. Who are they renting from? Even that’s

unclear in some cases – such as the student accommodation building named Dudley International

House in Victoria, which was used to launder $4.75 million in kickbacks to Malaysian officials. Or the

Sydney apartment blocks, Tasmanian dairy farms and a Hilton Hotel whose foreign owners only

came to light when they were exposed in the Pandora Papers leaks. If Donald Horne were alive

today, he might say the modern Australian ‘lacks curiosity’ about the source of this flood of

unexplained wealth. He might say Australians are ‘implausibly in denial’ about the influx of foreign

money, which is so critical to powering the country’s post-banking-deregulation economic miracle.

He might suggest the professional facilitators are also blind to the good fortune that allows

undisclosed buyers to make cash offers on multimillion-dollar waterfront palaces, after a weekend’s

gambling at one of Australia’s equally accommodating casino complexes. In our comparable regional

neighbours – Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Hong Kong – questions must be asked

of any prospective wealthy property purchasers. Not here. Unfortunately, this means that many

trusting modern Australians – in a world that has grown deeply suspicious of cash offers on real

estate – are too often ‘taken by surprise’.

It’s abundantly clear that not all of the money that props up the world’s most buoyant property

market is the savings of hardworking Aussies. A significant slice of that $9 trillion is the proceeds of

criminal wealth. This is money tainted by the stench of foreign corruption, tax evasion, drug deals,

environmental crimes and human trafficking. The sheer gravity of the world’s ‘black economy’,

worth around $US2 trillion each year, ensures an incessant flow of illicit money. Australia’s high

levels of public trust, and the facade of our ‘clean’ economy, makes it an ideal place to park the

proceeds of human trafficking, illicit drug production or bribery. The country awoke to news that

the nation’s proudest financial institution, the Commonwealth Bank, had become a wash-house for

international crime syndicates. The system was so efficient that the criminals didn’t even need to

speak to a teller. Technology handled the cash deposits for them. Drug syndicates, Middle Eastern

terrorists and other major crime groups had managed to move billions of dollars – to this day, no

one knows the exact amount – through the same bank that was giving primary-school kids their first

Dollarmite account. Police surveillance footage showed money mules sitting on milk crates on the

footpath outside a suburban Commonwealth Bank branch, stuffing the ATM with bricks of green

and gold banknotes from a dishevelled backpack. A year later the rot spread to Westpac. The

nation’s oldest bank was caught moving funds for the country’s worst sex offenders, facilitating

unspeakable crimes against children in the Philippines. Westpac had also been running a crossborder financial sluice gate that allowed multinational clients to book Australian revenue in low-tax

countries such as Singapore. The money slipped through the fingers of the ATO and landed in the

hands of more forgiving offshore tax collectors. Who knows what happened to it then? It certainly

didn’t pay for Australian roads, schools and hospitals. As with the Commonwealth Bank, Westpac’s

poor compliance controls and bad bookkeeping meant the ATO would never be able to shine a light

on this corporate tax evasion. The bank records had never existed to begin with.

After that, the dominoes fell. First it was Crown Casino in Melbourne and Perth, then The Star in

Sydney – the country’s two largest casino groups. All were embroiled in scandals involving junket

operators, criminal money, proceeds of corruption, bikie gangs and Asian triads. Australians were

less surprised to see grainy footage of ‘high rollers’ at Crown Casino unbundling millions of dollars,

in neatly bound bricks, from another Aussie icon: the supermarket cooler bag. One prolific gambler

moved $100 million in a single week through the pokies at The Star. Even the country’s sporting

clubs were implicated in systemic money laundering, after authorities discovered that criminals

were washing vast sums of money through the nation’s beloved pokies. Management had looked

away, feigning ignorance, as tax evasion and criminal cash kept the nation’s community sporting

clubs afloat. At least the listed casino chains weren’t having all the fun. In this instance, however,

Horne was wrong. Australia’s 25 million honest citizens weren’t just surprised, they were shocked

and appalled. They weren’t complacent – they were bloody furious. How could a country that

detested political corruption become the ‘safety deposit box’ for corrupt politicians from across

Asia, the Pacific Islands, Africa and Europe?

How could Asian triads and Mexican drug cartels swap synthetic drugs – near-worthless chemicals –

for some of the country’s finest freehold real estate? Australia was losing its precious farms and

waterfront development sites to criminal gangs, in return for fleeting chemical highs. How could

one of the world’s richest countries, a bastion of financial integrity, find itself in a position where its

politicians would lie to the world for 15 years about impending law reform that would close these

loopholes? Was all this pretence intended to uphold the system that had turned Australian housing

into one of the world’s criminal Ponzi schemes, or did some of Australia’s leaders so lack curiosity

about the events that surrounded them that they were unaware of the risks of the global criminal

economy? More to the point: how could Australians be certain they weren’t paying more for their

family homes because they were going head-to-head at auction with a drug dealer or a foreign

kleptocrat? Could Aussies still believe in the fairness that had been the foundation of the nation’s

social contract for more than 200 years? The truth is, they couldn’t. And they still can’t to this day.

Since 2006, those ‘Tranche 2’ federal money-laundering law reforms have been hand-balled from

one incoming prime minister to the next. The Ponzi scheme that is Australian property has

outlasted six of them. At best, Australia’s leaders ‘so lack curiosity’ about the events that surround

them that they’re unaware of the risks of the global criminal economy. At worst, Australia’s leaders

have a horse in the race and are knowingly complicit in this global scam. Welcome to the deep, dark

world of the modern criminal economy.

We need a new model, perhaps Norway has

We need a new model, perhaps Norway has

Eytan Lenko [who has a successful technical, business and entrepreneurship background and is a long running advocate for action on climate change] has already put before Government a report entitled

Eytan Lenko [who has a successful technical, business and entrepreneurship background and is a long running advocate for action on climate change] has already put before Government a report entitled

If you want financial advice about any other asset class, shares, derivatives, etc. the provider must comply with very

If you want financial advice about any other asset class, shares, derivatives, etc. the provider must comply with very

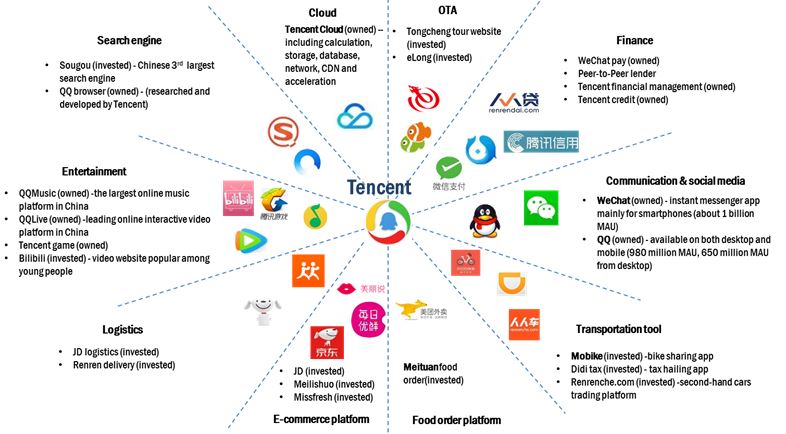

Pony Ma is the founder, president, chief executive officer, and executive board member of Tencent Holdings, Ltd., one of the most important telecommunications companies in China. Tencent, with its well-known penguin icon, controls China’s largest instant messaging (IM) service and has expanded to other mobile telephone and internet services. Ma’s interest in Tencent has made him quite wealthy, and he is regarded as one of China’s most desirable bachelors. Born around 1971, on the island of Hainan, China, Ma uses the nickname “Pony” which is derived from the English translation of his family name, which is “horse.”

Pony Ma is the founder, president, chief executive officer, and executive board member of Tencent Holdings, Ltd., one of the most important telecommunications companies in China. Tencent, with its well-known penguin icon, controls China’s largest instant messaging (IM) service and has expanded to other mobile telephone and internet services. Ma’s interest in Tencent has made him quite wealthy, and he is regarded as one of China’s most desirable bachelors. Born around 1971, on the island of Hainan, China, Ma uses the nickname “Pony” which is derived from the English translation of his family name, which is “horse.” end, he and four friends founded Tencent in 1998. They began the company with only $120, 000, primarily garnered from money earned while playing the stock market. The first years of the company were difficult. Ma had to wear many hats in the first year, from janitor to website designer, as the company lacked experienced employees and financial health.

end, he and four friends founded Tencent in 1998. They began the company with only $120, 000, primarily garnered from money earned while playing the stock market. The first years of the company were difficult. Ma had to wear many hats in the first year, from janitor to website designer, as the company lacked experienced employees and financial health.

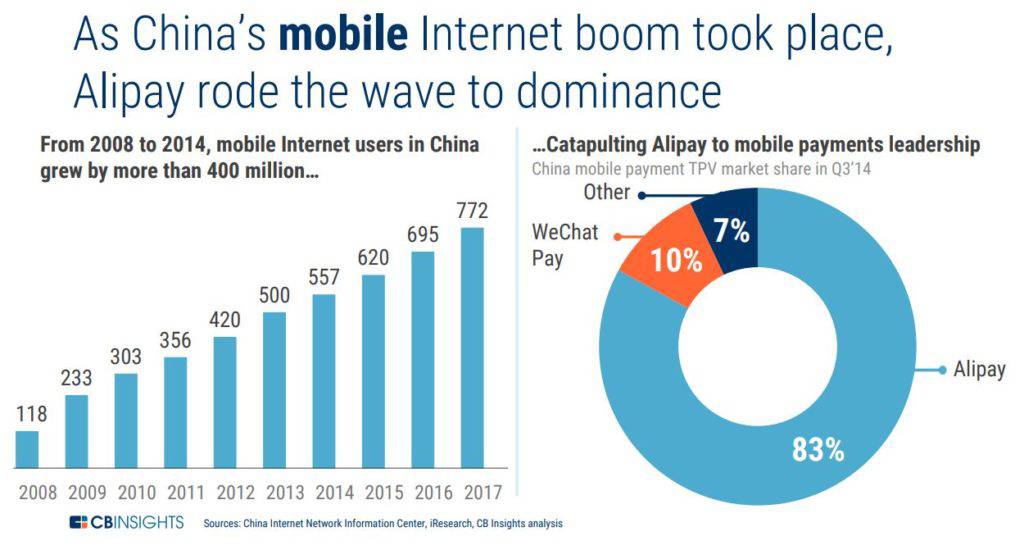

Alibaba, an e-commerce juggernaut matched in size only by Amazon. Mr Ma, who launched Alibaba from a small apartment in Hangzhou in 1999, is an emblem of China’s extraordinary economic transformation.

Alibaba, an e-commerce juggernaut matched in size only by Amazon. Mr Ma, who launched Alibaba from a small apartment in Hangzhou in 1999, is an emblem of China’s extraordinary economic transformation.

On 9 January 2017, Ma met with United States President-elect Donald Trump at Trump Tower, to discuss the potential of 1 million job openings in the following five years through Alibaba’s interest in the country. On 8 September 2017, to celebrate Alibaba’s 18th year of establishment, Ma appeared on stage and gave a Michael-Jackson-inspired performance. He performed part of “Can You Feel The Love Tonight” at the 2009 Alibaba birthday event while dressed as a heavy metal lead singer. In the same month, Ma also partnered with Sir Li Ka-shing in a joint venture to offer a digital wallet service in Hong Kong. Ma announced on 10 September 2018 that he would step down as executive chairman of Alibaba Group Holding in the coming year. Ma denied reports that he was forced to step aside by the Chinese government and stated that he wants to focus on philanthropy through his foundation. Daniel Zhang would then lead the way ahead for Alibaba as the current executive chairman.

On 9 January 2017, Ma met with United States President-elect Donald Trump at Trump Tower, to discuss the potential of 1 million job openings in the following five years through Alibaba’s interest in the country. On 8 September 2017, to celebrate Alibaba’s 18th year of establishment, Ma appeared on stage and gave a Michael-Jackson-inspired performance. He performed part of “Can You Feel The Love Tonight” at the 2009 Alibaba birthday event while dressed as a heavy metal lead singer. In the same month, Ma also partnered with Sir Li Ka-shing in a joint venture to offer a digital wallet service in Hong Kong. Ma announced on 10 September 2018 that he would step down as executive chairman of Alibaba Group Holding in the coming year. Ma denied reports that he was forced to step aside by the Chinese government and stated that he wants to focus on philanthropy through his foundation. Daniel Zhang would then lead the way ahead for Alibaba as the current executive chairman.

And those who lost their lives protecting the community, the owners of the 2000 plus houses destroyed, probably should have accepted the love of God, because, in private, away from the media, church members will say they should have made a bigger effort to be godly.

And those who lost their lives protecting the community, the owners of the 2000 plus houses destroyed, probably should have accepted the love of God, because, in private, away from the media, church members will say they should have made a bigger effort to be godly.

The New York World and rapidly increasing circulation through the publication of sensationalist stories he earned the dubious honour of being the pioneer of tabloid journalism. He soon had a competitor in the field when his rival William Randolph Hearst acquired the The New York Journal.

The New York World and rapidly increasing circulation through the publication of sensationalist stories he earned the dubious honour of being the pioneer of tabloid journalism. He soon had a competitor in the field when his rival William Randolph Hearst acquired the The New York Journal.

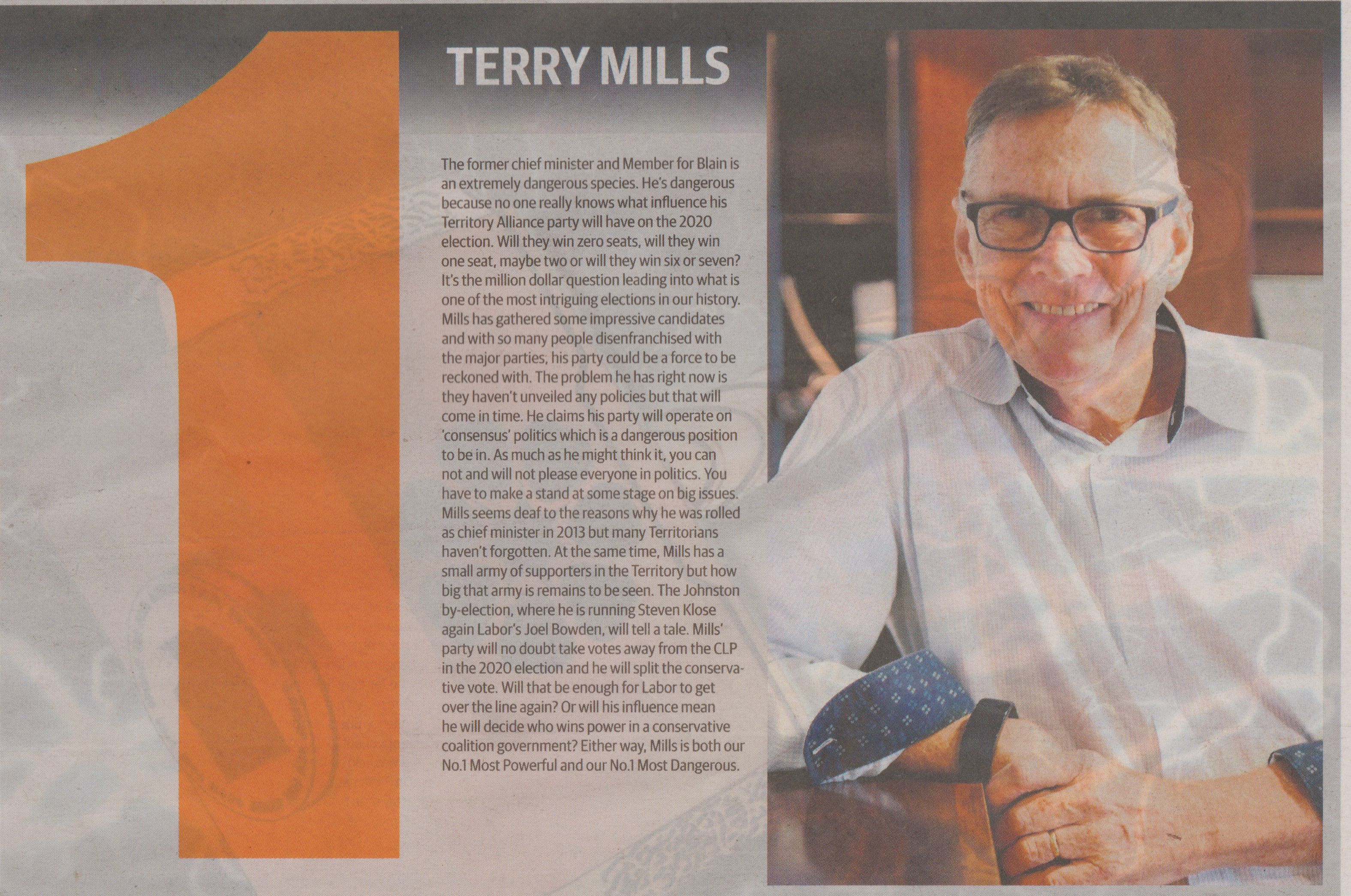

On Saturday 14 December the Empty News published two full pages of opinion centered on renewable energy, one by Ian Satchwell and the other by regular contributor Matt Cunningham from skyNEWS. The first is principal of Airlie Asia and former director of the Department of Chief Minister. The latter is simply a mouthpiece for Rupert, repeating whatever he is told is the “message” of the day.

On Saturday 14 December the Empty News published two full pages of opinion centered on renewable energy, one by Ian Satchwell and the other by regular contributor Matt Cunningham from skyNEWS. The first is principal of Airlie Asia and former director of the Department of Chief Minister. The latter is simply a mouthpiece for Rupert, repeating whatever he is told is the “message” of the day.

Another problem with today’s derivatives market is that the contracts are so loosely controlled that no one is really sure of the actual numbers concerning its size or structure. Governments have colluded with Wall Street and the banking industry to ensure there is no central clearing house for derivative transactions, no central reporting and no disclosure. Banks don’t tell investors how much of the “notional amount” that they could lose in a worst-case scenario, nor are they required to. Even a savvy investor who reads the footnotes can only guess at what a bank’s potential risk exposure from the complicated interactions of derivatives might be. And when experts can’t assess risk, and large bets go wrong simultaneously, the whole financial system can freeze and lead to a global financial meltdown. Meanwhile, there is no other game in town to realize the kind of profits banks and their clients demand these days, so the roulette table is the place to be. The big 4 merely left the housing market behind and started betting more furiously on other things, like the failure of the Greek economy, the hedge funds of maverick financial traders and who knows what else.

Another problem with today’s derivatives market is that the contracts are so loosely controlled that no one is really sure of the actual numbers concerning its size or structure. Governments have colluded with Wall Street and the banking industry to ensure there is no central clearing house for derivative transactions, no central reporting and no disclosure. Banks don’t tell investors how much of the “notional amount” that they could lose in a worst-case scenario, nor are they required to. Even a savvy investor who reads the footnotes can only guess at what a bank’s potential risk exposure from the complicated interactions of derivatives might be. And when experts can’t assess risk, and large bets go wrong simultaneously, the whole financial system can freeze and lead to a global financial meltdown. Meanwhile, there is no other game in town to realize the kind of profits banks and their clients demand these days, so the roulette table is the place to be. The big 4 merely left the housing market behind and started betting more furiously on other things, like the failure of the Greek economy, the hedge funds of maverick financial traders and who knows what else.

Great importance was soon attached to external marks of repentance — to tears, fasting, and mortification of the flesh; and inward regeneration of the heart, which alone constitutes a real conversion, was forgotten. As confession and penance are easier than the extirpation of sin and the abandonment of vice, many ceased contending against the lusts of the flesh, and preferred gratifying them at the expense of a few mortifications. Men were required to fast, to go barefoot, to wear no linen, etc.; to quit their homes and their native land for distant countries; or to renounce the world and embrace a monastic life.

Great importance was soon attached to external marks of repentance — to tears, fasting, and mortification of the flesh; and inward regeneration of the heart, which alone constitutes a real conversion, was forgotten. As confession and penance are easier than the extirpation of sin and the abandonment of vice, many ceased contending against the lusts of the flesh, and preferred gratifying them at the expense of a few mortifications. Men were required to fast, to go barefoot, to wear no linen, etc.; to quit their homes and their native land for distant countries; or to renounce the world and embrace a monastic life. The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the government system of the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy. It started in 12th-century France to combat religious dissent, in particular the

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the government system of the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy. It started in 12th-century France to combat religious dissent, in particular the

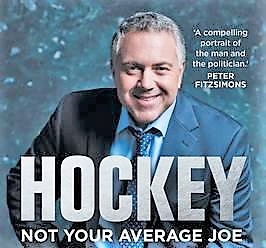

In a 2012 speech, delivered to London’s Institute for Economic affairs, Australia’s now Ambassador to the US, used the podium to rail against the pernicious effect of the welfare safety net, which had been constructed by sleepwalking Western democracies using tax revenue collected disproportionately from hard working folk [that voted for his party]. Some voters had become so used to the state providing healthcare, education and a social safety net that they had come to expect it, Hockey argued. Government spending on these social programs had reached extraordinary levels of GDP, and “people had come to believe that they had a right to a good or service that someone else was paying for. A weak government gives its citizens everything they want, but “a strong government has the will to say ‘No!'” Hockey lectured.

In a 2012 speech, delivered to London’s Institute for Economic affairs, Australia’s now Ambassador to the US, used the podium to rail against the pernicious effect of the welfare safety net, which had been constructed by sleepwalking Western democracies using tax revenue collected disproportionately from hard working folk [that voted for his party]. Some voters had become so used to the state providing healthcare, education and a social safety net that they had come to expect it, Hockey argued. Government spending on these social programs had reached extraordinary levels of GDP, and “people had come to believe that they had a right to a good or service that someone else was paying for. A weak government gives its citizens everything they want, but “a strong government has the will to say ‘No!'” Hockey lectured.

Sure they might seek to minimise their income for tax reasons, but at least they pay their own way, right? They don’t leach off government services. They made their money through hard graft. Except that no one gets that rich without the substantial aid, or in cases of outright corruption, the gift, of public assets – be they land, contracts or the use of infrastructure built by the taxpayer. The super-rich might not be availing themselves of bulk-billing GPs, but they still use airports and roads, hospitals and universities. When some one humbugs them in the street they expect that the police will sanction the perpetrator. And what would the entitlement-busters make of the behaviour of the big banks, who have been accused of mistreating and mischarging customers for years? The very same banks who availed themselves of hefty billions of taxpayer financial support during the Global Financial Crisis?

Sure they might seek to minimise their income for tax reasons, but at least they pay their own way, right? They don’t leach off government services. They made their money through hard graft. Except that no one gets that rich without the substantial aid, or in cases of outright corruption, the gift, of public assets – be they land, contracts or the use of infrastructure built by the taxpayer. The super-rich might not be availing themselves of bulk-billing GPs, but they still use airports and roads, hospitals and universities. When some one humbugs them in the street they expect that the police will sanction the perpetrator. And what would the entitlement-busters make of the behaviour of the big banks, who have been accused of mistreating and mischarging customers for years? The very same banks who availed themselves of hefty billions of taxpayer financial support during the Global Financial Crisis?

The current generation of seniors benefits far more from government spending, particularly on health. A principled approach to reforming age-based tax breaks would minimise their administration and reduce their budgetary cost, while maintaining the adequacy of retirement incomes and incentives to work. The best balance between these criteria would wind back SAPTO so that it is available only to pensioners, and so that those whose income bars them from receiving a full Age Pension pay some income tax. Seniors should also start paying the Medicare levy at the point where they are liable to pay some income tax. They would then pay a similar amount of tax to younger workers with similar incomes. This package would improve budget balances by about $700 million a year. Seniors also receive a larger rebate on their private health insurance than do younger workers with similar incomes. This larger rebate has no obvious policy rationale. It does not appear to increase private health insurance take-up. Seniors are already adequately protected from higher private insurance costs by “community rating” arrangements. The private health insurance rebate for seniors should be reduced to the same level as for younger workers with similar incomes. This reform would improve budget balances by about $250 million a year, after accounting for the additional government health costs as a small number of seniors choose to discontinue private health insurance.

The current generation of seniors benefits far more from government spending, particularly on health. A principled approach to reforming age-based tax breaks would minimise their administration and reduce their budgetary cost, while maintaining the adequacy of retirement incomes and incentives to work. The best balance between these criteria would wind back SAPTO so that it is available only to pensioners, and so that those whose income bars them from receiving a full Age Pension pay some income tax. Seniors should also start paying the Medicare levy at the point where they are liable to pay some income tax. They would then pay a similar amount of tax to younger workers with similar incomes. This package would improve budget balances by about $700 million a year. Seniors also receive a larger rebate on their private health insurance than do younger workers with similar incomes. This larger rebate has no obvious policy rationale. It does not appear to increase private health insurance take-up. Seniors are already adequately protected from higher private insurance costs by “community rating” arrangements. The private health insurance rebate for seniors should be reduced to the same level as for younger workers with similar incomes. This reform would improve budget balances by about $250 million a year, after accounting for the additional government health costs as a small number of seniors choose to discontinue private health insurance.