Ever asked the boss to sling you some cash, no questions asked, so you don’t have to inform Centrelink? Done a job and used a made-up ABN? Or maybe provided some work to a friend, for a couple of cartons and then written a receipt for service well under the real value?

You’ve just become part of the black economy!

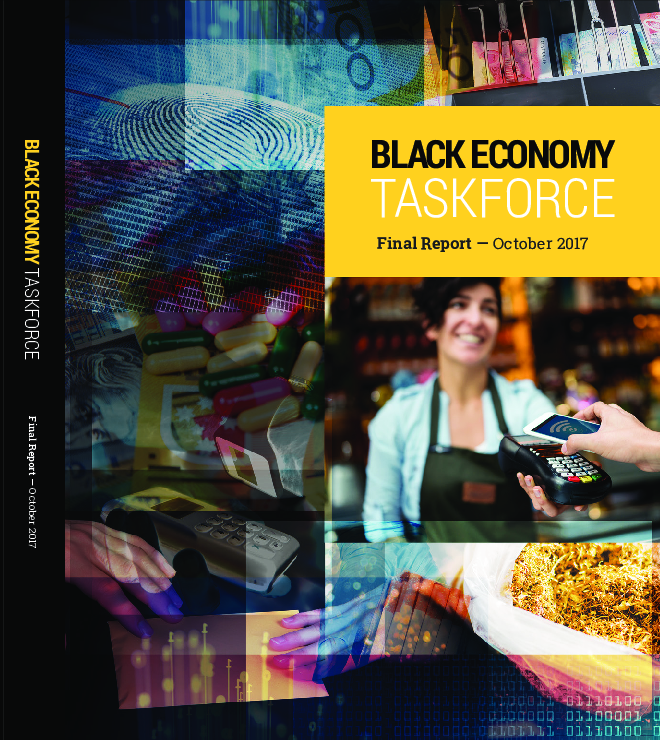

And, according to a report into the black economy, it’s worth $25 billion a year, getting bigger with the rise of the ‘gig economy’ actually encouraging more people to go dark. A Federal Government task force has been looking at the black economy, those transactions done out of the light of the tax system and official authorities, for several years .

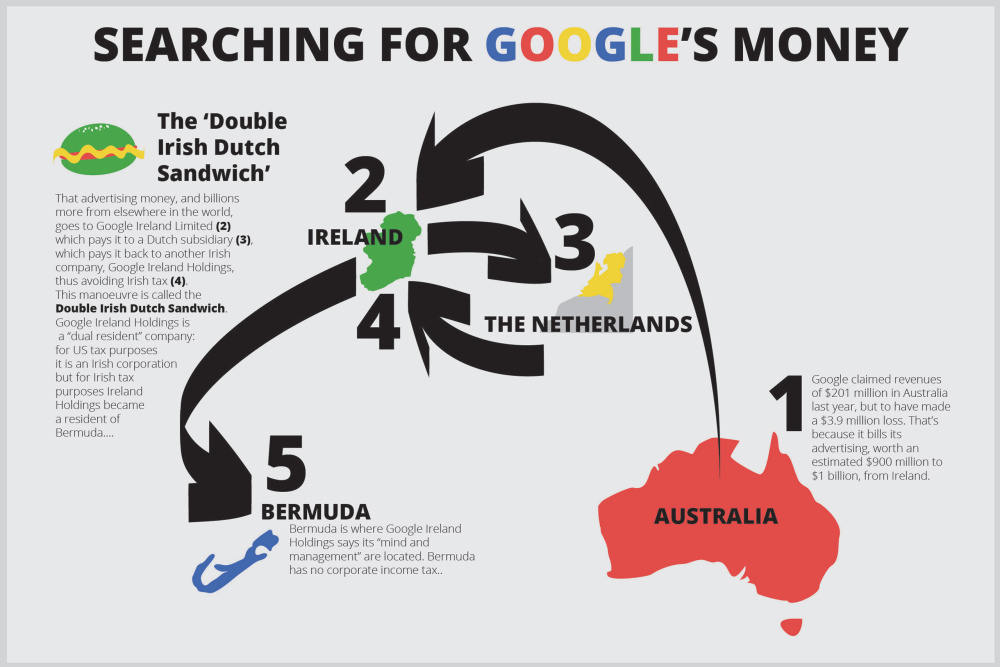

There are two primary concerns; from a purely financial perspective, the more activity there is in the black economy the less tax is collected. We might moan about the inefficiency of the ATO but, if a business or individual is finding a way to avoid paying tax, it puts them at a commercial advantage to those who are doing the right thing. [It also affects the GST system which means the more non-reported activity goes on, the fewer dollars there are to share among the States and Territories.]

The other concern is that illicit financial transactions are used by organised criminals and terrorists as they go about their nefarious business. While Uber and Airbnb offer us new ways to get about town or spend a night out of the town, their ‘sharing’ systems are being exploited by those who simply don’t want to pay tax. In terms of regulatory burdens, the task force highlighted taxation reporting procedures as one of the reasons businesses don’t play by the rules. That would suggest simply tightening laws or increasing red tape on firms is not going curb the cash economy, in fact, it could make it worse. The task force puts some faith in technology overcoming some elements of the cash economy.

Tap-and-go payment systems, for instance, make it much easier to track transactions, while biometrics will also make it tougher for individuals to avoid being caught up in the official economy. But technology works both ways. The allegations against the Commonwealth Bank and they way its “intelligent deposit machines” were used by organised crime and possibly terrorist financiers highlights the way technology can be misused. Criminals quickly worked out these machines, which enable the deposit of up to $20,000 in cash, could be exploited by those seeking to stay hidden.

The Bahamas is a constellation of 700 islands, many smaller than a square mile. It is one of a handful of micro nations south of the United States whose confidentiality laws and reluctance to share information with foreign governments gave rise to the term “Caribbean curtain.” For nearly a century, the Bahamas has been on the radar of tax officials around the world. In the 1930s, the U.S. Internal Revenue Service investigated Americans who avoided taxes in Switzerland and the Bahamas, which once sold itself as the “Switzerland of the West.” The focus intensified in the 1960s when U.S. investigators noticed an uptick in the use of the Bahamas by organized crime bosses. U.S. bank assets in the Bahamas, meanwhile, ballooned eight times between 1973 and 1979. By the end of the 1970s, one study reported that the “flow of criminal and tax evasion money” into the Bahamas was $20 billion a year.

To peek behind the curtain, a clandestine U.S. government project named “Operation Tradewinds” used IRS agents who paid an informant to enter the bedroom of a Bahamian banker visiting Miami and to remove his briefcase. At a nearby restaurant, another IRS informant provided the oblivious banker with “female entertainment.” The briefcase held a goldmine of information from one Bahamian bank on 308 U.S. account holders, including mafia kingpins, celebrities and corporate moguls, who reportedly held as much as a quarter of a billion dollars. Although the operation led to criminal prosecutions and $100 million in tax penalties, it was scrapped in 1975 after congressional outcry into the IRS’s use of informants. A U.S. court later declared the briefcase search “flagrantly illegal.”

In 2014, the most recent review of the Bahamas’ anti-money laundering systems by the OECD faulted the country on half of the core measures used to judge countries’ compliance with international standards. This included no requirement for banks or financial institutions to know the real identity of a company or trust owner. The Bahamas is on a par with Panama in terms of its thirst for and tolerance of dirty money, and, as governments push tax havens to share banking and financial information with national tax agencies concerned about offshore evasion by citizens, the Bahamas has pushed back.

The 11.5 million documents, leaked from Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca by an anonymous source shamed the rich and famous and took down world leaders. To date, it remains one of the biggest data leaks in history, revealing the hidden faces behind shell companies and offshore tax havens. Authorities across the world, including the Australian Taxation Office, moved immediately to investigate potential breaches of the law by their citizens.

And while the ATO has said prosecutions of individuals could take years to eventuate, in the United States federal authorities have already laid charges against several individuals. Since the leaks, the OECD has been encouraging governments to introduce a register that gives the public free access to the names of people behind secret assets and bank accounts. Known as a “beneficial ownership register”, it would make it harder for criminals to hide who they are and what they get up to. According to the head of tax at the OECD, Pascal Saint-Amans, this register is the final frontier in fighting tax evasion.

This register was also something that the ALP supports, and the former minister for revenue and financial services, Kelly O’Dwyer, said the coalition would look at. In a media release in February 2017, she noted it was a government “commitment” and announced Treasury would consult on how to best introduce a register and report back. But more than two years on, nothing has happened. There’s been much effort, by those who have a great deal to lose, to fight against anyone who wants to shine a light on murky business deals.

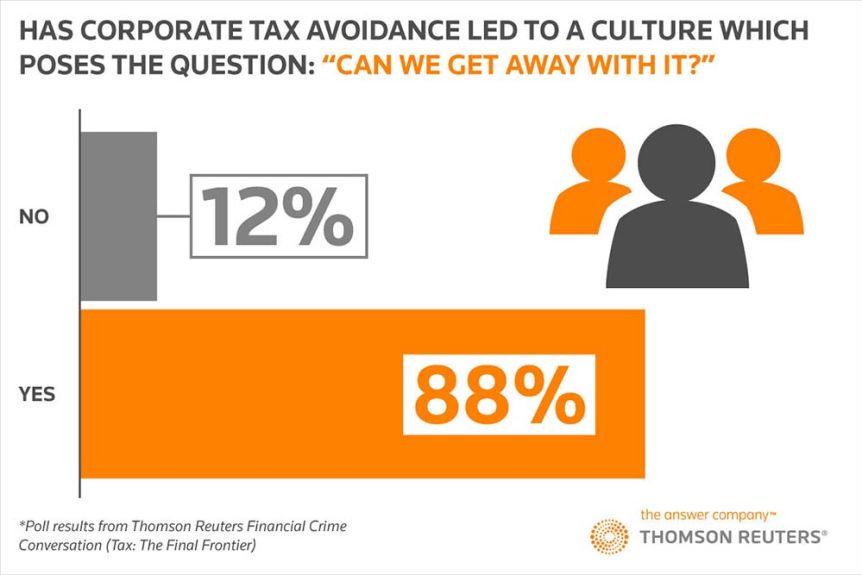

Despite most submissions to Treasury supporting the introduction of such a register, despite the Federal Government’s own Black Economy Taskforce calling for it, and despite Australian government agencies including the ATO, ASIC and AUSTRAC all supporting it, the Government has delayed the introduction. It appears that business and tax lobbyists have been successful in convincing Liberal ministers that a register is too much red tape, or perhaps some ministers may be embarrassed by an appearance.

The person now responsible for hearing their grievances, who ultimately has the power to see the policy through, is Assistant Minister for Superannuation, and Financial Services, Jane Hume. A spokesman for Ms Hume said: “The Government is committed to improving the transparency of information around beneficial ownership and control of companies available to relevant authorities, including the establishment of a central register.” Ms Hume might also want to take note of a review which looked at compliance with the UN Convention Against Corruption. This review made a number of recommendations for the Federal Government to improve its capacity to fight corruption, including introducing a beneficial ownership register.

Jane has a head start when it comes to understanding corruption in financial services, having begun work at the National Australia Bank in 1995. She rose quickly at the NAB, becoming an Investment Manager in 1996 and a Private Banker in 1998. In 1999, Jane moved from the NAB to Rothschild Australia Asset Management, assuming the role of Senior Business Development Manager.

Jane returned briefly to the full-time workforce in 2008 as a Vice-President at Deutsche Bank, before assuming directorship positions on various boards, and in June of 2015, Jane resumed full-time work at Australian Super as a Senior Policy Adviser, where she remained until her election in 2016. It may be a coincidence that NAB was most severely excoriated at the Bank Royal Commission and why absolutely nothing will result from their criminal activity. Similarly, Deutsche Bank is widely regarded as the probably cause of the next Global Financial crisis. Great work experience for oversight of corruption and the black economy in Australia.

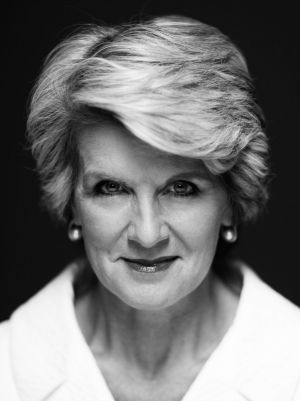

Julie Bishop was the coalition minister who privatised foreign aid spending. As foreign minister, Ms Bishop shut down AusAid, the Government’s aid delivery organisation, and opened up the foreign aid budget to private contractors. Now she is working for one of the biggest beneficiaries of that policy. Whatever she receives will be on top of the parliamentary pension, estimated by William Summers to be just short of $213,000 pa.

It’s probably impossible to unwind the relationship between any of the multinationals and their ’employees’ because these companies are notorious for functioning out of tax havens such as the Bahamas and Panama. It would be useful to look at the links between them and their ‘holding’ companies and determine how much [if any] tax is paid on their Australian Government revenue.

- ABT Associates, which is based in the United States and has offices in 50 countries, won a three-year contract worth $143 million in earlier this year to manage a “partnership fund” in Papua New Guinea.

- Coffey International Development, an engineering company that expanded into aid projects, was paid $22 million in June to supply “management services” for health programs in Fiji.

- Cardno Emerging Markets, which recently posted a $8.6 million net profit, was paid $29 million over four years to managing a program for village development in East Timor.

- Brisbane-based Palladium International was awarded a five-year contract worth $18 million this year to deliver “administrative support services” on Nauru.

In a speech announcing the new foreign aid policy Ms Bishop said ” … we will focus on effective governance to help development partners strengthen accountability, transparency and the rule of law. If nations don’t have good governance, if there is misuse, or corruption or other poor practices, we can hardly expect our aid dollars to make up the difference. We need to build the capacity of countries to control fraud and corruption and stamp out tax avoidance. Supporting anti-corruption measures is also a priority as corruption is pervasive in parts of our region. “

What, if anything, has been done to punish the ‘partners’ responsible for the provision of APEC conference transport?

Papua New Guinea has recovered 40 Maserati cars that vanished after being controversially bought for a recent Apec summit in the impoverished nation, but other vehicles remain missing. Government documents show that dozens of the sleek Maserati Quattroporte – worth at least US$135,000 each – have resurfaced at a wharf in Port Moresby. Three Bentley Flying Spur V8 vehicles worth at least US$410,000 each will also be sold by tender. Police have been called in to find an unknown number of the estimated 1,500 vehicles that were bought or donated for a recent summit. The government justified the purchase of the sports cars by saying it was in keeping with the prestige of the event.

Should Julie visit PNG in her capacity as Director of Palladium, she will no doubt be chauffeured about in a Bentley Flying Spur, courtesy of ABT Associates.

Some Australian politicians maintain that our political problems stem from a lack of engagement by voters. But can we trust people who have a demonstrated conflict of interest and who make decisions based upon rewards deferred to the end of their political career rather than for the good of the country?